Andy Morrison: Ex-Manchester City star goes from battling demons to becoming a champion

- Published

Connah's Quay manager Andy Morrison opens up on dealing with depression

Amid the wait to see what would happen to the Cymru Premier season, the man with more at stake than anyone was the calmest.

Andy Morrison, manager of the side four points clear at the top before the season's suspension, was almost serene as he talked of the uncertainty meaning little in the grand scheme of things.

It was impressive for someone who was so close to leading his club, Connah's Quay Nomads, to a first domestic title.

And it was even more notable to those who remember Morrison the player, an intimidating, fiercely committed and streetwise Manchester City centre-half.

Morrison the manager has not lost any toughness.

The 49-year-old often appears every bit as uncompromising in the dugout as he was when he was hailed for dragging Manchester City "kicking and screaming" out of the third tier in 1999.

The fire remains, but the destruction it often left behind does not. For Morrison, who has suffered depression and battled with alcohol, calm has replaced chaos.

"I sometimes hear people who are close to me defending me at times, saying you don't know Andy, you don't know who he is or what he's about, but it's just how things are," Morrison tells BBC Sport Wales.

"You can spend your whole life trying to prove people wrong, but it's much easier to prove that you're right. You only have to do that to one person."

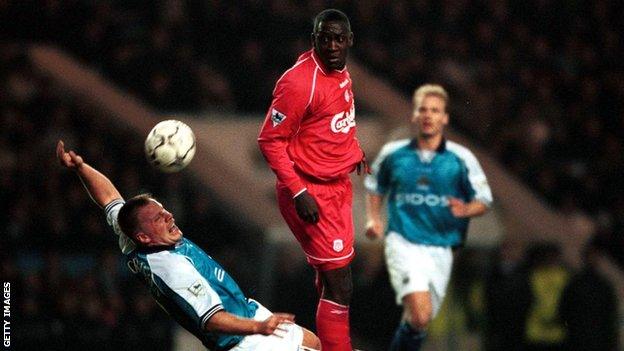

Andy Morrison, here challenging Liverpool's Emile Heskey, played for Manchester City in the Premier League having joined the club in the third tier

Morrison has proven something to himself almost every day for two decades, since the days when looking in the mirror was a far tougher ask than it is now.

"The lowest point? Waking up in a cell in Inverness," he says. "The reality of opening your eyes and seeing the bars and the four walls and that feeling of 'what have I done?'. Checking your hands, feeling your face, did you get a gold or silver medal in the fight? No idea of what had happened the night before, just waiting to find out how bad it is.

"If somebody had opened the door and said you're being charged with murder, I wouldn't have known.

"That point was a lonely, horrible place."

Change was coming, but only after many steps down a path that Morrison says would have led to prison, hospital or a graveyard.

"You couldn't keep on doing what I was doing and get away with it," he adds.

'A belly full of beer and a head full of anger'

Born in the Scottish Highlands but brought up in a "tough" area of Plymouth, Morrison started his football career with Argyle and played for the likes of Blackburn, Blackpool and Huddersfield as well as Manchester City.

Along the way there were off-field incidents and warnings Morrison says he was not ready to listen to. No matter how sobering the situations, the "demon drink" would win out.

"Not every time I drank there was trouble, but every time there was trouble I was drunk," he says.

"There were so many episodes of feeling I'd let people down, being in really strong positions in my career and then ultimately the demon drink would come back and I'd find myself in incredible situations that I shouldn't have been in with the responsibility I'd been given.

"I'd captained every team I played for and trained right, worked hard, (been) relentless in my desire to win, but when I stepped away from that and I drank alcohol, all the demons in me - which were barbaric at times - (meant) I'd get in that situation time and time again.

"You'd promise the manager, you'd promise your wife, you'd promise your parents, that's it, it won't happen again - but you never said I won't drink again."

Morrison believes a childhood incident - disclosed in his autobiography - where he was physically abused by two men in a Plymouth park created "darkness and demons" which he "didn't have the tools to deal with when they came along at 3am with a belly full of beer and a head full of anger".

"I understand today where that rage and that barbaric behaviour came from, but it took me a long time to understand that," he adds.

Morrison also cites a need to escape from the pressure of playing and the demands he placed upon himself as an on-pitch leader.

"I've had probably over 20 operations in my career and the best way I would describe it is like the point when the anaesthetic goes in and you're off the world and gone until you come back around," he says.

"I needed that every two or three weeks."

The power of conversation

It was while at City in January 1999 that a weekend off - thanks to suspension - led to an incident with a doorman, a smashed pub window and that cell in Inverness.

Morrison returned to City to face manager Joe Royle, and a conversation that changed his life.

"I sat with Joe and started with the apologies again, but he stopped and asked about me," Morrison says.

"Rather than saying 'you're a disgrace', he cared about me as a human being. It turned around for me there and then."

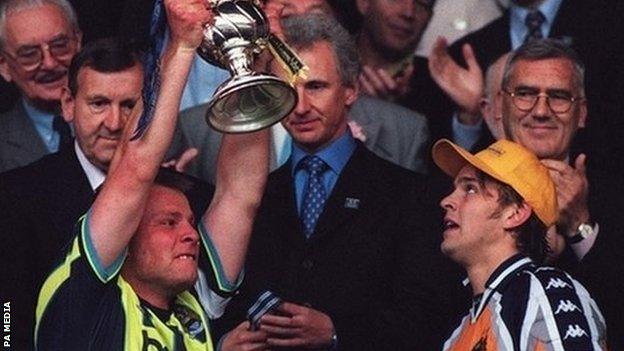

Andy Morrison celebrates after Manchester City's play-off final win over Gillingham in 1999

Morrison went to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting that week, and continued to do so in the years that followed.

He has not drunk since - and was not tempted by the champagne that flowed at Wembley after skippering City to play-off final victory in 1999.

"There are people who have probably had to wait years for their life to turn around after the (kind of) chaos I had," he says.

"I'm very, very, very lucky because there's a lot of people who don't get that opportunity and aren't here to tell their story."

Injury leads to depression

The struggles did not just disappear, though. After another promotion and appearances in the Premier League, Morrison's career was ended by a knee injury.

He admits bravado probably stopped him looking for help even before he had to retire aged 31, and that fear turned to depression as he faced up to the fact he knew nothing other than football.

"I had to go into the big wide world with no trade, no qualifications, but you stick your chest out and say another door will open," Morrison says.

"But only when you look back do you see how hard it was, how mentally draining (it was) and how low you were."

When support came, Morrison used it and, in time, has sought to help others.

As a coach, he worked for non-league clubs before taking over a struggling Connah's Quay side in 2015.

He has overseen five successive qualifications for Europe football, a Welsh Cup triumph and now the Cymru Premier title.

Last season Connah's Quay reached the Scottish Challenge Cup final, while they knocked Kilmarnock out of the Europa League in 2019-20.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Yet for all the on-field success, Morrison says part of his job is to help any player trying to cope with the kind of challenges he faced.

"I want to win, I need to win, but I'm also conscious of helping them fulfil their potential as human beings as well as footballers," says Morrison, who recently completed a PFA counselling course.

As a result Morrison has had regular contact with his squad during lockdown, and not just to check on their training schedules.

He enjoys training too.

"I find that when I train it keeps the voices in the head quiet," he says.

Yet it is definitely Morrison doing the talking now, rather than his demons. He was always seen as a winner, and now he can - calmly - call himself a champion. For more reasons than one.

If you or someone you know has been affected by issues raised in this story, help and support is available at bbc.co.uk/actionline