Grenfell Athletic: The football club healing the wounds of a disaster

- Published

- comments

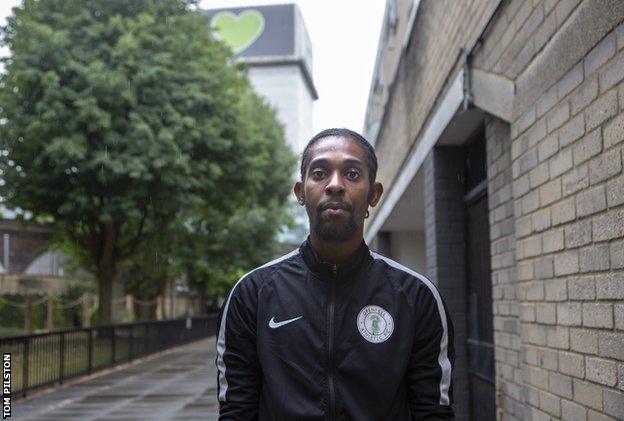

Joseph says football has helped him escape the trauma in ways he couldn't before

Joseph John was about to get into bed in the early hours of 14 June 2017. He heard noise coming from outside the second-floor apartment he shared with his partner and 14-month-old son in the Grenfell Tower.

He looked through his curtains and saw a fire engine. He then caught a bright red reflection in the window of a parked car.

"I saw the building was on fire," Joseph, 29, recalls.

He woke his partner and rushed out of the flat to seek help. Joseph's partner is disabled and he needed help in evacuating his family from the 24-storey tower. A firefighter told him to go back inside the flat and someone would assist them in getting out.

But after an hour, as flames engulfed the tower's upper floors, he and his partner realised they couldn't risk waiting any longer. Joseph passed their baby over a large gate to a stranger downstairs before carrying his partner through the window and over the gate himself.

They managed to get out just in time. Seventy-two people did not. Joseph is still struggling to process the trauma he experienced. He suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety.

A few months after the fire, Joseph heard about a new local football team that had started up. A keen player, he eventually decided to check out a training session.

Finally, he could take his mind off what had happened that night.

"I tried cooking, I tried working, I tried everything," he says. "Nothing seemed to work for me, other than football."

Joseph wasn't the only one. This is the story of a very special Sunday league team, Grenfell Athletic.

The Grenfell Tower fire in North Kensington, west London, was one of the worst disasters in British modern history. It began on the fourth floor of the tower just before 01:00 BST on 14 June. By 04:30 more than 100 flats were on fire. The blaze did not burn itself out for 24 hours.

Rupert Taylor was born and raised on the streets surrounding Grenfell and used to play on football pitches beneath the tower. He started volunteering as a youth worker in 2005 and at the time of the fire was manager of the local youth centre. Nine children from the youth centre died in the tower.

Justice4Grenfell says more than 23,000 homes in the UK are still covered in "Grenfell-style cladding"

Rupert was on holiday in Gibraltar when he received a phone call in the early hours of 14 June.

"I turned on the news. My heart sunk, it was horrific," he recalls. "We didn't know who was alive."

He got the first plane back to London and got straight to work in helping people affected by the fire. "When I got back I drove in… the smell of burning was real," he says. "I was trying to get support for the residents who were wandering the streets trying to find out about their loved ones."

A few days later, Rupert noticed a young man wandering outside the youth centre looking lost. He asked the man if he was OK and if he wanted to come in and get some supplies. He politely declined but they exchanged phone numbers. The man later came into the centre and they started to talk. He told Rupert he was a resident of the tower.

"He seemed like a very lonely chap," Rupert says. "He told me that he'd lost both his parents a few years ago. A couple of weeks in, we were building a relationship and I noticed he was really struggling. I asked what helped him get through the time when he lost his parents and the first thing that came out of his mouth was 'football'.

"I said: 'Right, we're going to create a team.'"

Inside the Grenfell Athletic changing room - the team started up for the 2017-18 season

Grenfell Athletic was born barely a month after the fire. Rupert started to put word around the local community and training sessions were set up.

Because it was so soon after the fire, he wanted it to be as open as possible. Many were still recovering mentally and physically, and he wanted residents to feel able to pop in for training sessions without fully committing to the team.

Grenfell Athletic joined the Middlesex County Football League for the 2017-18 season. The early days were turbulent.

"It was the strain of the shadow of what we were all walking out for," Rupert says. "The 72 lives that were lost. Every time we went out to the pitch, we did a minute's silence. It starts to wear you down and it's quite heavy on the soul.

"Children lost their lives. You're seeing their faces when you get out on the pitch and you say you're doing this for them. You're trying to build something greater than your bog-standard Sunday league team."

Grenfell Athletic soon started to gel and finished fifth out of 12 teams in their first season - a solid start for a new team founded under such tough circumstances.

At the end of the season, the team went on a tour of Italy where they played semi-professional Lanciano from the Italian fifth tier. The trip was an important part of the healing process for a lot of the players, many of whom hadn't properly left the area since the fire. It was, Rupert says, "a time for them to be away from the shadow of this area and the tower".

Bonded after their Italian tour, the team fully found their stride in the second season. They lost just one game and won both the league - gaining promotion - and League Cup.

Rupert (right) celebrating with the team's League Cup trophy last year

After the fire, Joseph and his family had to spend the first few days living in a local church, before eventually being given a room in a hotel - where they stayed for a year. They have been in temporary housing since.

As time went on, Joseph struggled to come to terms with the night of the fire. He knew people who lost their lives. He recalls a family he would chat to and help out in the tower's lift. They didn't make it out.

"For me, it was super difficult, even now. Every day I feel like I am living back in 2017," he says.

Joseph, who moved to the UK four years ago, is from a family of footballers and grew up playing in his native Trinidad and Tobago - even representing his country at under-17 level.

The team soon helped him escape the trauma in ways he hadn't been able to before. He also started opening up to some of his team-mates about the fire.

"It helped me grow bonds with them, it helped me be open. I can discuss anything with some of my team-mates," he says. "We can chat one to one - man to man - it makes me feel comfortable.

"I don't like being around people, I don't like meeting people, I don't like being in people's space - I like to be around myself. But in football you can't have that.

'Football is my family, football is my community," Joseph says

"You have to be respectful, you have to be considerate to your team-mates, you have to be uplifting. It's different rules - being part of the team."

By mid-March of this year, Grenfell Athletic were joint second in the table, and then coronavirus hit.

"Right now my mental health is going down badly with no football and just staying at home," he said in April. "I can't go to my physio, I can't go to my therapist. It's hard."

Many of the team did not live in Grenfell, but the tower had been a constant in their lives.

Boxer Dan-Dan Keenan, 23, grew up in the area and started training at the Dale Youth Boxing Club inside Grenfell Tower aged 10.

Dan-Dan was outside the tower on the night of the fire, speaking to his best friend's father, Tony, on the phone. Tony was trapped on the 23rd floor and never made it out.

"I rang him when I first got there to tell him there was a fire and he said 'thanks for making me aware but I already know,'" Dan-Dan recalls. "We were watching it, so it's pretty bad."

Dan-Dan soon heard about Grenfell Athletic from local friends he grew up with playing football.

"I wanted to get involved in remembrance of Grenfell and especially in remembrance of Tony. But also, besides that, I just wanted to play football," he says.

"It means that everyone is still talking about Grenfell, which is always a good thing. Obviously we want to remember them and not just let it get swept under the carpet."

Grenfell Athletic are now hoping to establish a permanent home in the local area

While the club is still in its infancy, everyone you speak to from Grenfell Athletic is dreaming big.

Rupert is eyeing up a plot of land in Greenford, west London, that could one day be the team's official home (they currently play around six miles away in Chiswick).

Dan-Dan says that a home ground of their own would help build the team's profile.

"I see a lot of Sunday league clubs - YouTube teams, for example - and they've got hundreds and hundreds of people watching and supporting them," he says.

"If we can get a home pitch which is local to Grenfell I'm sure people - whether they like football or not - will come and support us just because we are representing Grenfell."

Joseph agrees that a real home and top-quality coaching is needed for the team to take the next step up and bag more silverware.

But the importance of Grenfell Athletic goes far beyond titles and trophies for Joseph.

"I have no family here, I'm here on my own with my kids and my partner. Football is my family, football is my community," he says.

"They're like my brothers. Well, they are my brothers."