Jimmy Carter: The story behind the Premier League's first British Asian player

- Published

Pictured here for Liverpool in 1991, Jimmy Carter also spent almost four years with Arsenal

Kenny Dalglish walked over to Jimmy Carter in the Liverpool dressing room and handed him his new shirt. It wasn't just any shirt - this was the number seven, one with a special place in the club's history.

Then Reds manager Dalglish had worn it. So too had Ian Callaghan and Kevin Keegan, celebrated players dear to Anfield hearts.

It was 12 January 1991, and Carter had only signed for the reigning English champions from Millwall two days earlier. The winger, aged 25, was about to make his debut. But there was something many did not, and still do not, know about him: he was a player with Indian heritage.

"That was probably one of the best moments in my life and one of those moments I'd dreamed of as a kid," says Carter of being handed the shirt.

"I looked at the back of the shirt, I looked around a little bit - a few of the players are watching with a few little smiles. You can imagine, every single one in that Liverpool dressing room was an international.

"To think that Kenny had just come up and given me that seven shirt - this skinny little Indian boy who grew up in Stoke Newington. It does not get any better than that. Incredible."

Carter's move to Liverpool did not work out. Dalglish left soon afterwards and his successor, Graeme Souness, deemed him surplus to requirements.

He left to join Arsenal and, when he made his debut for the Gunners in August 1992, became the first British Asian to play in the Premier League. It would take 11 years for another to follow in his footsteps.

In an English game where players from that background are conspicuous only by their absence, none of the handful of the British Asian players since Carter have scaled the kind of heights he rose to in playing for such illustrious clubs.

Now aged 55, Carter admits his Indian background still comes as a "shock" to many when they learn of it and, because of his surname and light skin tone, "no-one really identified" him as being of Asian origin during his career.

"I think they just saw a guy running up and down the wing, thinking: 'He doesn't mind the odd sunbed or two,'" he says.

The truth is, he was much more than that.

Carter explains that his surname dates back to an English ancestor from the 17th Century who, after moving from London to India, married an Indian woman and settled in the country.

His father, Maurice, was born to Indian parents in Kanpur and brought up in Lucknow in the north of India, where he attended La Martiniere College, a prestigious private school established in 1845 under colonial rule.

Maurice was orphaned at the age of 14 and, left "lost" with "no family to speak of", joined the Indian merchant navy when he was 16.

"He sailed the seas and loved his sport," Carter says fondly. "He was a boxer in the navy and turned out to be one of their leading boxers of all time. He had 38 fights and never lost one."

Maurice eventually came to England and married an English woman but, after having two boys, the pair divorced. Maurice took custody and brought his sons up in Hackney, east London, "essentially as Indian kids".

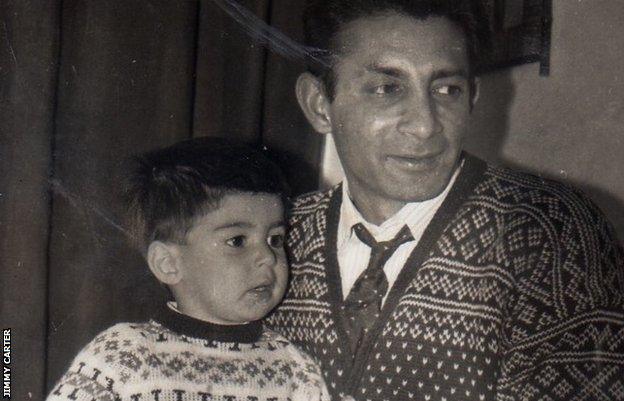

A young Carter pictured with his father, Maurice

"Our mum was English but whenever my dad could afford meat we'd have curry and rice," Carter says. "When he couldn't afford meat, he'd drop a few boiled eggs in the sauce of the dhal and we'd have it with rice. That's how we were brought up.

"He sacrificed everything. He was a qualified City & Guilds leather technician and had job offers all over the world, but he had to put everything on hold to bring us up.

"He would take menial jobs just to be able to take us to nursery. He'd be stacking shelves in an off licence just to know that he could drop us off at 9am and pick us up at 3pm."

Carter had a "tough" upbringing during the 1970s and 1980s. Suffering racist abuse was a common part of a far from regular life, the beginnings of a rags to riches journey that would not be out of place in a Bollywood script.

He would be woken at 6am by his father on frosty winter mornings and ordered to go out running in his local park to "get one over" the other kids trying to make it as footballers. He would also be told to get some milk off someone's doorstep on the way back if they had none at home.

Maurice also liked to gamble and would sometimes tell Carter and his brother, who were "free dinner school kids like Marcus Rashford", not to run around at playtime as there would be no evening meal because he had lost his money on the horses.

Sometimes, though, Carter says, "he won and we'd go up to Drummond Street in Euston and we'd have a curry and buy Indian sweets".

On the pitch, despite "getting kicked all over the place" and dealing with "major abuse" playing for his youth team, Carter was picked up by Crystal Palace when he was 14.

"Whenever I got abuse, I always wanted to prove the person who instigated that racism wrong," he says. "I wanted to humiliate him on the football field. That would be my answer back.

"I would never go back home and tell my dad. I knew how much that would hurt him.

"He would've thought that because of his skin colour, my skin colour is what it is and, because of that, I got racial abuse and there was nothing he could do about it.

"I took it on myself and became thick-skinned. It made me more determined.

"You have to show them that: 'Yes, you called me that, but that Indian boy you just tried to kick has just humiliated you; you are going to be reading about me and watching me play for the biggest clubs in world football.' That's how I spun it round."

Carter and Jan Molby, pictured in February 1991, following Kenny Dalglish's resignation as Liverpool manager

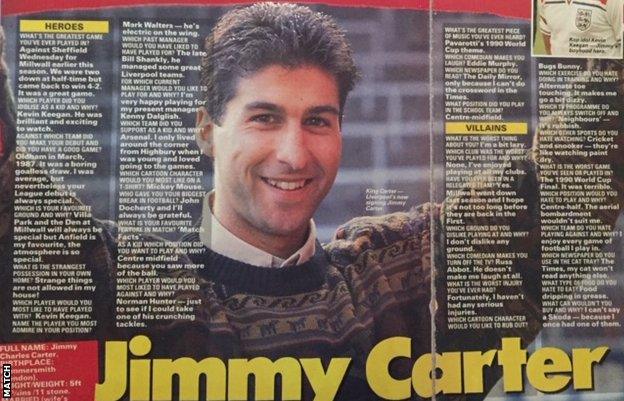

Carter's dream of making it big took a hit when he was released by Crystal Palace at 19. He worked his way back into the game at Queens Park Rangers before making his name at Millwall.

Aged 22, Carter was part of a Lions side that won the old Second Division title in 1988. With Teddy Sheringham and Tony Cascarino in the team, they were promoted to the top flight for the first time.

Still, only those closest to him - such as Sheringham, who had played in the same Sunday team growing up - knew about his Asian background.

"My second chance came at Millwall," Carter says. "Football was very different back then and I felt there was no real need to disclose my Indian heritage - it was just about playing.

"Hardly any of my team-mates knew of my Asian heritage apart from Teddy. I always felt welcomed at Millwall but I'd sometimes get a few racial comments from the opposition just because I looked a bit different.

"Looking back, they were comments which you probably couldn't get away with now, but I never took them to heart. For me, it just made me more determined.

"To get on in football, if you were to take offence or have any bitterness towards it and bite back, then I probably would have got a harder time. It's not nice to hear, but it was a different era back then.

"It was all about getting your head down and making sure you stayed in that first team to better your career."

Carter did just that as Dalglish came calling and he moved to the reigning English champions Liverpool.

Carter's time at Liverpool would be cut short. He moved on to boyhood club Arsenal in October 1991.

British Asians to have played in the Premier League since Carter include Michael Chopra, who made his debut for Newcastle United in May 2003, and Zesh Rehman, whose first appearance for Fulham came against Liverpool in 2004.

At present, there are 10 British Asians among 4,000 professional footballers in the UK - that is 0.25% compared with 7% of the population as a whole.

So, does Carter regret not making more of his Asian heritage to help inspire others from the same background?

"When I signed for Liverpool, there was never any mention of: 'Do you have any Asian background or foreign heritage?'" he says.

"I was very lucky to get my second chance in football and what I didn't want to do - looking back - was bring anything to attention which could possibly be seen as a detriment to me. There were no Asian players back then.

"People would still talk about black players saying they didn't like it in the cold, or that Asian players were too lightweight. I couldn't afford for anything to be brought up where it was going to be a detriment to my career.

"If I had highlighted my British Asian heritage it would have, perhaps, shone a light on being the first one to ever play for Liverpool and Arsenal.

"It could have given that belief to youngsters up and down the country, that they too could make it. But, on the whole - even taking that into consideration - I still don't have any underlying regrets.

"There is part regret that I wasn't able to feel strong enough or have the conviction at the time to actually come out and shine a spotlight on it. But outweighing that was the fact that, to do that would be pointing myself out as someone different, when it shouldn't be like that. It shouldn't be about the colour of your skin.

"It has to feel right in all aspects for you to disclose something. It wasn't a conscious decision that: 'I'm going to keep this a secret.' It was nothing like that.

"If people came up to me and said, 'I spoke to your dad the other day, I didn't know you were Asian', I was pleased as punch. I would never be one to hide that."

Carter's playing career ended in 1999 with a final stint at Millwall, following spells at Oxford and Portsmouth. He now works as a co-commentator for radio and does some work for the English Football League. He lives in Hertfordshire, on the outskirts of London, with his wife and two children.

He still makes dhal like his father used to when on cooking duties.

"I'm very proud of my Asian heritage and the fact that my father was so proud," says Carter.

"All he ever wanted me to be was a sportsman and to realise the ability I had - to strive and be the best I could and to reach the top. I was able to make him proud when he was alive.

"Looking back at my career, to think that I played for two of the biggest clubs in world football - I'd have to take that from where I was as a little kid."

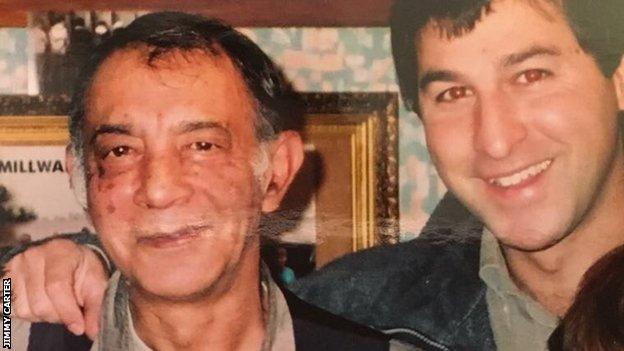

Carter, pictured with his father Maurice, who passed away in January 2009

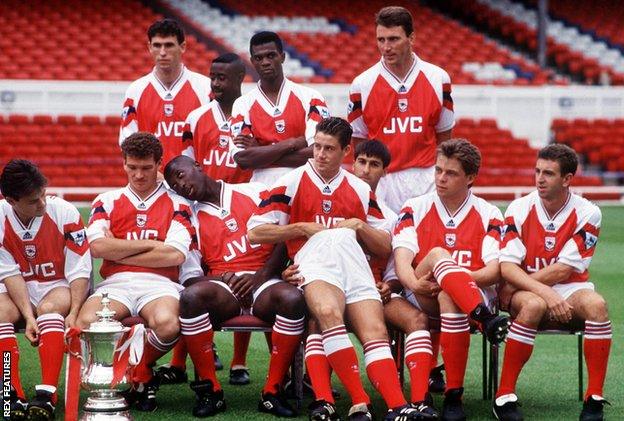

The Arsenal team pose for a photo in August 1993. Carter is partially obscured in the front row, third from right

Sir Paul McCartney chats to Idris Elba: The music legend reveals his writing process and most-loved songs

The Cipher: Can you crack it? Thrilling new drama that will keep you gripped