Why are there so few BAME players in English women's football?

- Published

"You have to question if the system is really working," says Aston Villa's Anita Asante, left

On Tuesday, England women play Northern Ireland in their first game for almost 12 months - a match introducing the new interim manager Hege Riise.

Notably, however - with Demi Stokes injured and Nikita Parris unable to travel because of Covid-19 restrictions - there will be only one non-white player in the squad of 21. Bristol City forward Ebony Salmon has been handed her first senior England call-up, after the initial all-white squad was announced.

Compared with the men's game, the pool of BAME players to choose from in women's football is a lot smaller.

At the Women's World Cup in 2019, Stokes and Parris were the only non-white players in the England squad. In the men's World Cup squad, external the year before, there were 13 players of colour - celebrated as "representing modern, multicultural England".

While women's football has grown exponentially in the past few years, the number of black and mixed-race players in an England squad for a major tournament has decreased from six in 2007 to two in 2019.

The statistics on BAME representation in English football can be difficult to pin down. Indeed, the football authorities faced criticism last year, external for not monitoring the number of elite players in the men's or women's games.

But Manchester City and England forward Raheem Sterling, speaking to the BBC's Newsnight programme last year about the lack of BAME coaches and leaders in English football, indicated that "there's something like 500 players in the Premier League and a third of them are black".

That figure was backed up when Paul Elliott, chairman of the FA's inclusion advisory board, spoke to the BBC around the same time.

It is estimated,, external though, that the proportion of BAME players in the Women's Super League is lower - at between 10-15% BAME players in the WSL.

"Right now, to be honest, it's not inclusive enough. And it's not diverse enough, and we know it," said Baroness Sue Campbell, the Football Association's director of women's football.

Accessibility & opportunity

Aston Villa's Anita Asante, 35, who has 71 England caps, says one reason there are so few BAME players in elite women's football is inaccessibility.

"It's getting more difficult to get the right accessibility for disadvantaged groups of young girls, especially in inner cities," she told BBC Sport.

"When you're seeing so few [BAME players] making it to the elite level you have to question if the system is really working. Does it need reviewing to find where the gaps are?"

Kay Cossington, the FA's head of women's player development and talent, told She Kicks magazine, external in 2020 that "inclusivity was compromised as we attempted to turn more professional. We had 52 centres of excellence; that was too many for the depth of talent at the time".

With 52 centres reduced to 30 - and with many of the centres that remained based in rural areas - a lot of the BAME players from big cities were travelling two or three hours to get to training. Millwall, for example, had trained in Lewisham and Southwark, but moved to Bromley where facilities were better.

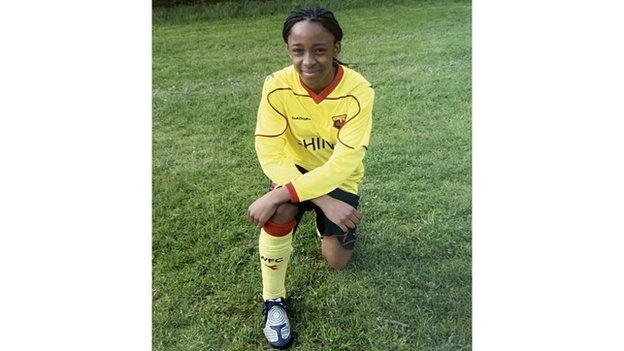

Adekite Fatuga-Dada is Watford's longest-serving women's player

When Watford forward Adekite Fatuga-Dada was 16, she was invited to an England Under-19s camp at St George's Park in Staffordshire, 144 miles from London. But her mum, a single parent, was working on the day of the camp, so Fatuga-Dada had no way of getting there.

Her mum asked the FA if they could help her daughter - then playing for Arsenal's Under-17s - with transportation. The FA told her to ask one of the Arsenal Women first-team players for a lift to the camp.

"I didn't feel comfortable to go and ask an Arsenal Ladies player who I've idolised growing up, if I could jump in the car with them," Fatuga-Dada, now 24, told BBC Sport.

She added: "I was so young and [my mum] didn't want me to travel on my own, which is understandable. But I don't think it's fair to ask every girl to do that. There should be more help.

"It was a very exciting time for me, I was on cloud nine as a young player. But I never went [to the camp] and I haven't been back with England since."

What is the FA doing about it?

The England squad after the 2019 Women's World Cup third place play-off defeat to Sweden

Baroness Sue Campbell says the FA wouldn't let what happened to Fatuga-Dada occur now.

"We'd find a way now," the FA's director of women's football told BBC Sport.

"When I first came into the FA five years ago, there were very few people focused on the women's game. Now we have somebody in every division of the football association with a key leading focus on the women's game."

Campbell says one challenge is not having the resources of the men's game. But she says that now women's football has the "volume through participation", the FA needs to redesign the pathway for its emerging talent, external.

The FA is also working with the EFL Trust to carry out more talent identification work in inner-city areas and has provided scholarships for players who need financial support. It says it is already seeing more ethnic diversity in the England youth teams.

The teenage drop-off

The FA also has an Asian Women's Advisory Group, and through its Wildcats programme, external for girls aged 5-11, it has trained coaches from the communities it is targeting - so that girls have relatable role models. There is also a new teenage equivalent programme.

But when the drop-off rate from sport for teenage girls is so high anyway, external, what is being done to make sure all the FA's work with youth is translating into the elite level of football?

"We've developed a programme for clubs, which is about helping clubs think about what it means to be girl-friendly and inclusive," Campbell said.

"It doesn't just mean you run a women's team. It means the whole ambience of who greets them, what the changing rooms look like, what is going to help them come along, feel that they belong, and that they're part of it.

"If you go that first time and it feels uncomfortable, most girls don't have the confidence to go back again."

So is it just a case of this work trickling down and waiting for the impact to be made? Or does the problem run deeper than that?

The perception of women's football, post Sampson

Eniola Aluko spoke to the BBC about Sampson claims in August

There are other issues for women's football that are unrelated to the talent pathway. In 2017, the FA apologised to England players Eniola Aluko and Drew Spence for racially discriminatory remarks made by sacked England women's boss Mark Sampson. It was a high-profile case that made headlines for more than a year.

Villa's Asante, who was playing in the squad at the time, said: "For young girls from similar backgrounds watching that, they would have probably been disheartened to have seen the negative impact it had on those individuals and also the actions at the time of the squad.

"That perception or lack of support for the person experiencing a form of discrimination or racism to the nation publicly, is not going to have a positive image or impact to young people.

"That's why it's important that the FA and us as players talk about these experiences, to try to improve the system so that it can be better for the next generation."

Asante says that since the global resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, her team-mates have reflected on the situation.

"I've had players that I know reach out to me personally and apologise," she said. "Not because they did something directly bad, but because they didn't reach out or they didn't support myself and those players at the time."

'A white space' and stereotypes

Fatuga-Dada says another problem for young players of colour is stereotypes.

"It is very much a white space," she told BBC Sport.

"A lot of black players that I know would be told the reason why they weren't getting picked for squads is because of things like attitude. I guess now you look at it and say that's a stereotype.

"It was tough - we were kids, and you can't argue with the manager or say 'I don't have a bad attitude, I'm not what you think I am'.

"It was so easy to discourage certain players from playing, because they were just told 'this is what you are'.

"If there are not more black, Asian or minority players at a grassroots level, we can't expect them at the top. If they do have the talent, why are we not trying to encourage them to reach those heights?"

If you can't see it, you can't be it

Asante says the lack of representation - both on the team and behind the scenes - is another challenge, especially as the number of BAME players has decreased in the past few years.

"From leadership to organisation management, the lack of representation is a barrier," she said.

"People don't have that connection necessarily to the game, because they don't see people that look like them or have their shared lived experience."

Asante remembers England legend Rachel Yankey leading a training session when she was a teenager at Arsenal, and says it made a huge difference having someone she could relate to.

She said: "She comes from a similar background - and all of these connections that we could build made me feel like this was a space that I really wanted to be in."