Richarlison: The work ethic and humble origins behind Everton forward's rise

- Published

Richarlison could face FA action after picking up a flare at Goodison Park

The battered, red-brick bus station in the small Brazilian town of Nova Venecia has a story to tell.

Backing on to a murky canal, with its £2 all-you-can-eat buffet and a drunk passed out on the forecourt, it marks the start point of Richarlison's journey to the Premier League.

Aged 17 and disheartened by serial rejection, it was from here that he left home on an 11-hour, 600km trip to Belo Horizonte, with borrowed boots and no money for a return ticket.

It was 2014. Trials at Avai and Figueirense had gone unrewarded, his beloved national team had been humiliated on home soil at the World Cup. Attracting little attention despite being top scorer with Real Noroeste Under-20s, the young forward was losing hope.

He considered the bus journey west - for a trial with second-tier side America-MG - his last big chance. He was determined not to give up.

"I remember that day," childhood friend Pedro Emanuel tells BBC Sport.

"He told me he was going, but didn't have any boots. In truth, he had a black pair but they were falling to bits. I told him: 'Man, there's a pair here, eye-catching blue and pink ones, you should take them.' Thank God everything worked out."

It certainly did work out, the trial eventually leading to five consecutive seasons in the Premier League with Watford and Everton. On the international stage Richarlison is a Copa America winner, a 2020 Olympics gold medallist, and a certainty for this year's World Cup in Qatar with Brazil.

Yet it all could have been so different.

Richarlison's parents separated when he was six, so he spent three years living with his father Antonio, working on his grandfather's farm helping harvest coffee beans, travelling long journeys every weekend to play matches.

By age seven, people were telling Antonio to invest in his son because he had special talent. He responded by buying 10 footballs and sending him to live with an aunt in Nova Venecia.

"We were very poor at that time," Antonio tells BBC Sport, dressed in the training kit of Nova Venecia FC, of which he is the president and his son is an ambassador.

"It was a very difficult childhood for him and difficult for me too because we lived in the countryside and every week we had to climb on the back of a lorry to get to football matches. People kept saying he had a future though, so when he turned nine I left him with my sister."

Richarlison helped pay his way by selling ice cream and chocolates on the streets, washing cars, working in a cafe with his uncle Elton, and trying his hand as a bricklayer's assistant.

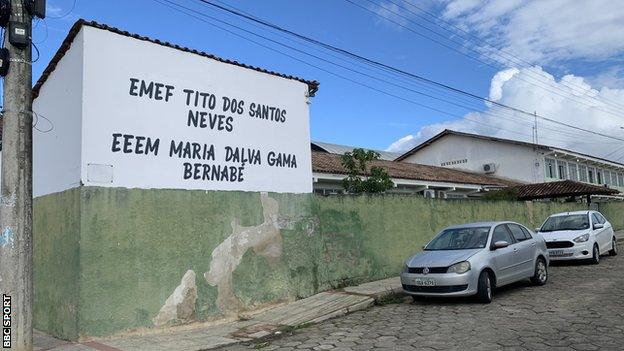

While Antonio admits his son was not the most academic of children, staff at the Tito dos Santos Neves school in the rough neighbourhood of Rubia describe a well-mannered, football-mad boy with dyed yellow hair like his idol Neymar. The school janitor recalls him bursting through the front gates every day and running directly for the yard at the back to play football. Teachers remember his humility and good behaviour.

"He didn't like to study, but he wasn't undisciplined," says Elisangela Monteiro Guidi, who taught Richarlison when he was 11.

"He was always well-behaved; he wasn't a rebellious boy by any means. He had respect for his teachers and that came from his family, who are good people. For sure, at that time and in this area, he might have got involved in drugs and violence, but he always managed to avoid that."

Not quite always. Aged 14, Richarlison had a gun pulled on him by a local dealer who believed he was trying to encroach on his territory. And Antonio recalls being summoned by the school on another occasion after his son was picked up by police on the street.

"We were worried because the area at that time was dangerous," Antonio says. "But it was more a case of being caught in the middle. Unfortunately, a lot of his friends went the wrong way."

Richarlison's old school - he would burst through the gates to play football in the yard before class

Richarlison credits his first youth coach, Fidel Carvalho, a policeman, as another who helped him steer clear of a life of crime. "Never give up," was Carvalho's motto. He recalls squeezing eight of the team into a VW Gol to contest a final out of town. The future Everton forward travelled in the boot and they returned as champions.

By age 16, Richarlison was playing as an amateur with Real Noroeste and dominating the Under-20 age group, his strength and pace proving problematic even for those three years older. Yet things ended sourly when the club's negotiating tactics saw his 2014 move to America-MG almost collapse.

After much back-and-forth, Real were allowed to retain a percentage of his rights, but the club's hardball stance affected the mental health of Antonio, who was already suffering from depression. To this day, Richarlison does not like to speak about this period of his career.

If leaving Real proved difficult, the youngster adapted to life at America easily. One of only two boys selected from the trial to which he travelled by bus, he joined the Serie B club's U17s before being fast-tracked into the U20s following four goals in his first four appearances.

America director Euler de Almeida Araujo remembers being impressed by his strength and determination - honed from running up and down the hilly, cobbled streets of Nova Venecia. Weeks later, he was training with the first-team.

"He played on the wing and would be fouled a lot but would rarely go down," says Araujo.

"Defenders would smash into him and he'd fall. You'd think he must be hurt, but he would bounce back up and keep going. He never gave up. He was like a young Ronaldo in that sense - that physical strength and determination at such a young age."

Richarlison moved to Nova Venecia as a young boy to live with his aunt

Richarlison's competitiveness was not reserved solely for the field. America's massage therapist Silvio Junio Nunes da Silva remembers having to take his young son to work one night before a match.

"Richarlison was playing PlayStation, so my son asked if he could play too," he says.

"I left them to it, but when I came back, Richarlison was winning 11-0. I said: 'Enough already, man.' But he was ruthless. He wanted to keep scoring, keep winning. He was 17, my son was seven. That desire to win is in his blood."

Marcelo Toscano played up front with Richarlison in 2015 as America were promoted to Serie A. He remembers a player with talent, humility - and a large nose.

"He was a lot of fun; we always joked back and forth. Back then, we called him Toucan because, I mean, it's not small, is it?" Toscano says.

"I said from the start that he would go far - because of his work ethic, his determination, his talent, and his humility. We scored a lot of goals that season and it's no coincidence he is where he is today."

Richarlison only stayed at America for a year, scoring nine times in 24 appearances before being sold to Fluminense for R$10m (worth £1.6m today) aged just 18. Yet he clearly left an impression - and not only because they retained 20% of his economic rights, thus receiving a windfall when he moved to Watford in 2017 for £11.5m. Speak to anybody at the club and they have a tale to share about their famous former colleague and his humble outlook.

For example, when a youth player at America receives their first professional salary, club rules dictate they should leave the academy dorms to free up a space for someone else. Richarlison, rather than renting the nice apartment his agent had identified, preferred to continue living with his team-mates - and the occasional rat that frequented the bedrooms in the evenings. He withdrew only 20% of his first salary and used the rest to support his family back home.

"He was a simple guy, very humble, and just a really good person who helped everyone he could," says Ze Ricardo, the America full-back who lived with Richarlison in the dorms.

"The boys who didn't have boots, he gave them his. He has a super good heart."

That humility and empathy has remained even as his career has rocketed.

Antonio adds: "He had a very close relationship with his grandad and his great-grandad - everyone says the same things about them; humble, hard-working people.

"We always taught him to carry that with him. Even today, I always say that he mustn't lose that essence. He must keep his feet on the ground.

"And he does. Whenever he comes to Nova Venecia he helps whoever he can. If it was up to him, he would still walk up and down the streets in his flip-flops, playing football with the children in the fields, just as he did before. Unfortunately, it's more dangerous for him now, so he does more online."

Richarlison's dad Antonio pictured in Nova Venecia FC's club gym

Few active players, if any, are as vocal as Richarlison when it comes to social issues. He has helped raise awareness and funds across a broad spectrum of charitable work including on deforestation, Brazil's rape crisis, combatting Covid-19 and the importance of voting in this year's presidential elections.

In 2019, shortly after paying for a group of Brazilian students to fly to Taiwan to compete in an international maths quiz, he broke protocol when receiving the most prestigious honour available to an athlete in his home state of Espirito Santo. Requesting the chance to address the floor, he urged the regional government to invest more in education.

A year later and after organising a charity match in Nova Venecia that generated 6.4 tonnes of food for those in need, he was named Everton's PFA Community Champion.

"All of us who play in big leagues and have space in the media, we have a great social responsibility," he told the club's official website.

"At first, I just wanted to buy a house for my parents, but then I saw that I could do bigger things."

Testament to his popularity at Everton can be found in the fact that even as his club finds itself embroiled in a relegation battle and rumours link him to a move away - a potential reunion with Neymar at PSG perseveres - nobody could realistically question his commitment. He continues to leave every inch of his six-foot frame on the field.

It may not be the characteristic most often associated with Brazilian footballers, but it bodes well for his chances of success at what will be his first World Cup later this year.

"It's a dream he has had since he was a child watching Ronaldo in 2002," says Antonio, just a short walk from the battered, red-brick bus station where it all began.

"That final, he was just a little boy; now, God willing, he's going to be there playing. I always told him he would play at the World Cup.

"And, just so you know, I also told him he would be top scorer, so let's see..."