Johan Cruyff: Total Football and the World Cup that changed everything

- Published

In the fourth of our World Cup icons series, BBC Sport tells the story of how Johan Cruyff and the Netherlands' Total Football captured the world's imagination in 1974.

It was a summer that played out in an orange haze. One of floppy-haired Dutchmen letting their revolutionary brand of football loose on the world and cavorting their way into the hearts and minds of the adoring public. It was Johan Cruyff's summer. At least, it almost was.

As he ground-hopped through West Germany in 1974, Cruyff embraced each game with more of a dance than a duel, his every stroke of leather compelling and each balletic movement steeped in vision and expectation.

Just the mention of his name transports you to Dortmund's Westfalenstadion, 19 June, the 24th minute - the moment Cruyff conjured up an unmistakable turn that bamboozled Sweden's Jan Olsson and was cast in football folklore.

"The turn wasn't something I'd ever done in training or practised," wrote Cruyff in his autobiography, My Turn. "The idea came to me in a flash, because at that particular moment it was the best solution for the situation I was in."

Yet that piece of skill, the inventive, individual moment of brilliance he is remembered most vividly for, was a beautiful contradiction.

Cruyff was the face of Total Football - a style of play where success blossoms with a collective, almost telepathic understanding of space and movement among all 11 players - but he was also the one star that could break the mould.

Cruyff was the essence of a team who captured the imagination with football as vivid and resplendent as their orange shirts, including leaving their mark on a mesmerised future Arsenal manager.

"I discovered completely new football," recalled Arsene Wenger at the Cruyff Legacy Summit. "When you speak today about pressing, transition and winning the ball back quickly, in 1974 Holland did that already.

"They were miles ahead tactically. They believed in the way they think about the game and they were not ready to compromise with their ideas: 'That's the way we see the game and that is the way football has to be played.'"

It was a concept that began with Ajax, the club based just five minutes from Cruyff's childhood home in Amsterdam. 'Jopie' joined as a 10-year-old, his mother later got a job there as a cleaner following his father's death, and it was Ajax that helped supplement him leaving school at 15 by faking his age to offer him a "special" youth contract.

Under the guidance of the great Rinus Michels, Cruyff became an integral part of a side that would go on to dominate European football during a boom for Dutch clubs.

Michels, himself influenced by Hungary's Magical Magyars in the 1950s, developed a style of football that would see Ajax win their first European Cup in 1971 and - after he left for Barcelona later that year - watched as the side he built collected three successive continental crowns.

"Michels made us run less and take over each other's positions, which was revolutionary," Ruud Krol, former Ajax and the Netherlands defender, told Uefa.

"It was the first time there was a totally different vision of football. Total Football spread all over the world. It was the only real change for almost 40 years. He stunned the world."

By 1973 Cruyff, about to claim his second Ballon d'Or, was an Ajax star and an idol for youngsters in the Netherlands at a time of social and cultural change.

Young people related to his practical approach and admired his exceptional talent. He was unwittingly cool - as a teenager he would stub out cigarettes on his boot soles - but he could also be confrontational, demanding and rebellious.

"He said you must do this in a game or you must do that," team-mate Johnny Rep remembered in David Winner's book Brilliant Orange. "It was not easy for me to shut my mouth."

Cruyff wore the Ajax armband, but during a summer training camp the squad voted Piet Keizer in as captain. Furious and feeling undermined, it spelled the end in Amsterdam for Cruyff, who called it a "form of jealousy I had never before experienced".

He left Ajax to join Michels in Barcelona for a then world-record £922,000 and helped the Catalan side to a first La Liga title in 14 years.

Cruyff experienced problems with some of his former colleagues during the international camps that followed, believing they were complaining about him arriving late from Spain or for not travelling with the team. But those feelings had softened by the time they regrouped to prepare for a tournament that would change many of their lives.

The Netherlands' record of qualifying for major tournaments was, frankly, rubbish - they had not reached a World Cup finals since before World War Two and had never appeared at the European Championships.

Even for the 1974 tournament they almost made a hash of qualifying, relying on a controversial offside decision in the final game against Belgium to see them through; Jan Verheyen's 89th-minute winner was chalked off, despite replays showing the Belgian was being played on by a number of Dutch defenders.

Czech manager Frantisek Fadrhonc was replaced by Barcelona boss Michels for the finals. It turned out to be a masterstroke.

Michels' squad was largely comprised of players with an Ajax connection and those from Feyenoord, who won the European Cup in 1970. But there was a surprise call up for FC Amsterdam goalkeeper Jan Jongbloed - the cigar shop owner who won his only previous cap 12 years earlier and was selected predominantly for his ability on the ball.

The Ajax contingent were well versed in the coach's pressing style and switching of positions, while the rest of the squad had the system drilled into them during a pre-tournament camp at the leafy KNVB headquarters in Zeist. Michels wanted Ajax 2.0, the ultra-attacking remodel.

It took time to click and they lost a friendly to a second division German team while trying to familiarise themselves with the tactics, but just one week before the World Cup started they enjoyed a morale-boosting 4-1 victory over Argentina.

"Total Football requires talented individuals acting in a disciplined group," said Cruyff, who had a huge influence on team selection. "Someone who whines or doesn't pay attention is a hindrance to the rest, and you need a boss like Michels to nip that in the bud.

"Total Football is, aside from the quality of the players, mostly a question of distance and positioning. When you've got the distances and formation right, everything falls into place."

Archive: The Cruyff turn is born at the 1974 World Cup

The Netherlands opened their first World Cup campaign in 36 years against Uruguay at the Niedersachsenstadion in Hannover, stepping out in orange shirts trimmed with the iconic three stripes of Adidas along the sleeve. All bar Cruyff's, that is.

He was contracted to Puma and had already refused to wear Adidas boots when playing for the national team, despite a KNVB deal with the manufacturer. At the World Cup - after a standoff between the brands, Cruyff and Dutch football bosses - it was decided his kit would have one of the stripes removed.

"The KNVB had signed a contract with Adidas without telling the players," Cruyff wrote in his autobiography. "They thought they didn't need to because the shirt was theirs. 'But the head sticking out of it is mine,' I told them."

"Those two stripes belong to me," he later wrote in a column for Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf, when the row reignited 40 years later after Cruyff's clothing company released a replica of his 1974 jersey.

In Hannover, Cruyff was the target of some rough Uruguayan treatment but glided over tackles and carried the Netherlands forward in a move that resulted with Rep giving them the lead after seven minutes, later adding his second to complete an opening victory that provided a glimpse of the side's potent mix of a smothering press and effortlessly fluid attack.

Four days later the Dutch played out a goalless draw with Sweden - a match remembered for one of the most iconic flashes of brilliance the game has ever witnessed.

Cruyff received a diagonal ball on the left of the Swedish box. His first touch almost let him down but a seemingly elasticated right leg wound it back in again and, once under control, the game of cat and mouse was on.

The shaggy-haired Dutch skipper exaggeratedly shaped to knock the ball back down field with his right foot, luring Olsson to take the bait, and with the Sweden full-back already moving in the direction of the anticipated pass Cruyff wrapped his boot around the ball, dragged it through his legs and was off towards the byline in an orange blur, leaving Olsson floundering in no man's land.

"There are impulses that arise because your technical and tactical knowledge has become so great that your legs are able to respond immediately to what your head wants them to do," wrote Cruyff. "Even if that's nothing more than a flash in the brain.

"I've always used feints like that. I've never used them to make the opponent look foolish, only as the best solution to a problem."

Olsson was convinced he was going to take the ball, and then it was gone.

"I do not understand how he did it," he said in 2016. "Now when I see the video, every time I think I have got the ball. I am sure I am going to take it, but every time he surprises me."

The move ultimately came to nothing and the Netherlands were unable to find a breakthrough, but Cruyff's moment of wizardry became the most recognisable image of that - arguably, of any - World Cup.

By the time the final group game against Bulgaria came round, the Netherlands were confident and won 4-1 against a side that included several of the CSKA Sofia team who ended Ajax's three-year unbeaten run in the European Cup earlier that season.

Cruyff, picked as the focal point in attack but dribbling into the box from the left, won a penalty from which Johan Neeskens put the Dutch ahead, adding another before the break while the captain toyed with and riled the Bulgarians and almost scored following a run from his own half.

Rep made it three after Cruyff sent the black and white tournament ball spinning into the area from a free-kick, before a floated cross from the Barcelona playmaker found a diving Theo de Jong arriving to cap a resounding win.

The Dutch were hitting their stride. Their football was captivating fans on the terraces and those watching from home, and their choir of orange-clad supporters was getting more vociferous with every scintillating performance.

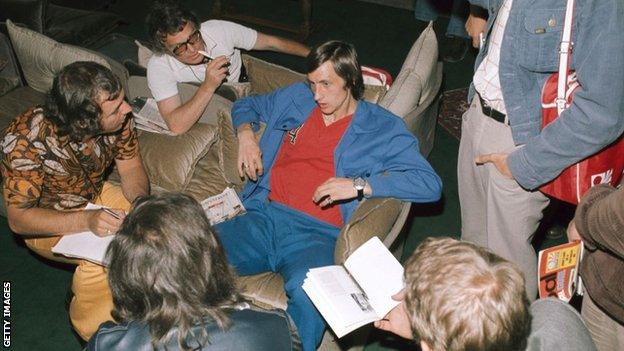

Cruyff talks to reporters at the Netherlands team's hotel in Hiltrup

The tournament format saw teams progress into a second group stage, with the Netherlands ripping through Argentina in their first game - the opening goal a perfect snapshot of their breathtaking style.

The Dutch recovered possession in the Argentina half and Cruyff plucked Wim van Hanegem's deft chip out of the air before rounding goalkeeper Daniel Carnevali and sliding the ball into an empty net.

Krol added a second and Rep then headed in a third from Cruyff's deep cross as boss Michels, raincoat covering his knees, observed from the bench with a flicker of a smile during a downpour in Gelsenkirchen.

The second-half weather could not dampen a display so dominant from the Dutch that goalkeeper Jongbloed touched the ball only once in the entire game. Cruyff added a late fourth with an instinctive volley from a tight angle to further whip up the hype around this team and their seemingly unstoppable captain.

"They said he would have made a good ballet dancer," Michels once reflected. "Honestly, I think Johan could have become anything he wanted to."

Jorge Valdano would go on to become a World Cup winner himself - and Argentina would get their revenge four years later in the final in Buenos Aires - but he watched in awe as a teenager as the Netherlands' number 14 tormented his compatriots.

"Never in my life have I seen a player rule matches like Cruyff," he said. "He was the owner of the show, much more than his team, the referee or the fans. His grip on what was happening on the field was amazing. He was a player, coach and referee at the same time."

Cruyff admitted to being tense in the early stages of the tournament but was now wowing the press with his manner off the pitch as well as on it - apart from one Dutch critic who was tossed, fully clothed, into the hotel swimming pool by the squad.

"Cruyff himself was a rapid and remarkable learner," said esteemed English football writer Brian Glanville. "Surrounded by a polyglot of journalists he dealt effortlessly with them in Dutch, English, German, Spanish and Italian."

Archive: Johan Cruyff scores twice at the 1974 World Cup

As June rolled into July the Netherlands were continuing to gather momentum and a 2-0 win over East Germany teed up what was essentially a semi-final against reigning champions Brazil.

This was a Selecao without Pele, who had left the national team in 1971 and revealed years later he refused to play in the 1974 World Cup in protest against torture by Brazil's military regime - instead he spent the tournament working for Pepsi.

Brazil still boasted the likes of Roberto Rivelino and Jairzinho, who missed a golden chance as the South Americans looked to take the initiative in the opening 20 minutes. But with the holders in blue and the Dutch in white, it was more than just their kits that were unrecognisable - it was a hot-tempered, physical battle.

"That was the best game, the hardest game - it had everything," explained Krol in Brilliant Orange. "There was nice football, nice combinations, dirty football. It was a game on the limits and I like that. Do everything to win."

Brazil collected three bookings in the first half, the Dutch one. But after the break Cruyff sprinkled some stardust on the skirmish with a pass from the right threaded between a pair of backtracking Brazilians for Neeskens to loop over goalkeeper Emerson Leao with a first-time effort.

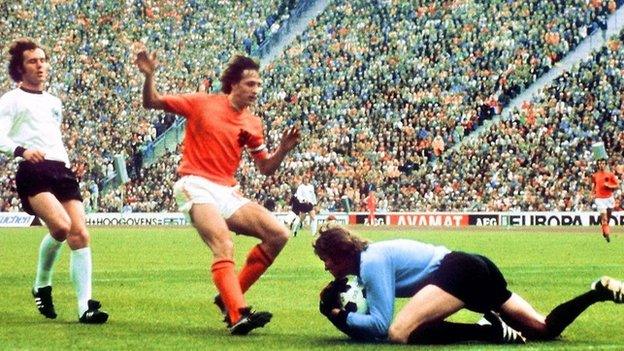

Their superior goal difference meant the Dutch only needed a draw to progress, but they made sure of their place in the final with 25 minutes remaining when Cruyff finished off a flowing move down the left by leaping on to a side-footed volley in mid-air. Luis Pereira was sent off for a hack on Neeskens late on as Brazil relinquished their grip on the trophy.

"It all came together in that game against Brazil," wrote Cruyff. "Until then, no one really knew how good we were, and the game against Brazil was probably the moment you could point to and say that was Total Football.

"When we walked on the pitch we were nervous, because we thought that we were still playing the team of 1970. It took us 30 minutes to realise that we were actually more skilful than them.

"Winning was the consequence of the process we had concentrated on. The first step was to bring enjoyment to the crowd, the next was the win."

The Netherlands had been so good, so compelling, their confidence was straddling arrogance. In an unusual calendar quirk, boss Michels even jetted back to Barcelona to oversee his club side play the Spanish Cup final mid-tournament.

But before the final there was unease in the Dutch camp as news reached home about a story in German newspaper Bild.

As Auke Kok explained in Johan Cruyff: Always on the Attack, Cruyff found being away from wife Danny and their three children "inhuman" and life at the Waldhotel Krautkramer in Hiltrup was becoming a bit of a drag.

In need of some entertainment, a group of players decided to host a now infamous party following the win over East Germany.

Volendam band The Cats performed, sparkling wine and cigars were enjoyed, and by 2am Cruyff and several others fancied a swim - naked - in the hotel pool, where they were joined by a group of local females.

"Little happened, other than a bit of flirting," wrote Kok. But unbeknown to the Dutch, there was also an undercover journalist present and the story appeared in Bild under the headline: Cruyff, champagne, naked girls and a refreshing dip. The captain was furious and spent hours on the hotel phone trying to placate his wife.

Cruyff always denied the incident and head coach Michels insisted it was an attempted smear campaign by the German press to unsettle the Dutch should they meet the hosts in the final.

And so they did, on 7 July at the Olympic Stadium in Munich.

Cruyff and his Dutch team-mates were unable to build on their early lead in the final

For many in the Netherlands, the German occupation during the war still carried huge cultural significance - midfielder Van Hanegem lost his father, sister and two brothers in the conflict.

It was, however, the bohemian Dutch who went into the final as favourites and there was huge optimism around the prospect of lifting a first World Cup.

"You could see it in their eyes," said German forward Bernd Holzenbein in Brilliant Orange. "Their attitude to us was, 'how many goals do you want to lose by today, boys?'. While we waited to go on the pitch, I tried to look them in the eye, but I couldn't do it. They made us feel small."

Dutch preparation was not ideal, compounded by losing their The Cats cassette tape and, the story goes, instead having to listen to David Bowie's Sorrow.

Cruyff did not sleep well the night before the final and instead sat up smoking in his room. He chewed gum as he stared into the crowd while the teams lined up before kick-off. For the first time, the Netherlands' huge following was massively outnumbered by home spectators.

The hosts had been booed during an unconvincing start to the tournament that featured a defeat by neighbours East Germany, and they were immediately left stunned by the Dutch as Cruyff went on a surging run, dummying and shimmying his way into the penalty area where he was brought down by Uli Hoeness - all before any German player had even touched the ball.

Neeskens converted from the spot to give Michels' men the perfect start and, as several players have since conceded, they set about trying to humiliate their hosts with the kind of football that won them so many suitors throughout the tournament - but, crucially, this time without adding to their lead.

"It was a classic case of pride coming before a fall," wrote Cruyff. "As soon as you're past that point of over-confidence, it becomes incredibly difficult to turn it around.

"Throughout the match everyone was either a bit too early or a bit too late - never on time. It just wasn't quite 100%. Sometimes you can lose a game in your head."

Despite their slow start to the competition, West Germany were also a very good side and moments after a glorious chance for Rep at one end, created by Cruyff, Holzenbein went down inside the box at the other. Paul Breitner levelled from the spot, and suddenly it was Germany's final.

Cruyff was a false nine long before the term was coined. He was everywhere during the World Cup: dropping deep as a playmaker, arriving late into the box, drifting on to the flanks. He created more chances and completed more dribbles than any other player in the tournament.

But as the Netherlands struggled to wrestle back control, the captain was dragged further away from goal, swamped by white shirts and unable to find space where he was so usually dangerous.

He came in for rough treatment from Berti Vogts, who was eventually booked, but then so was Cruyff for arguing with referee Jack Taylor at half-time after Gerd Muller had given the hosts the lead. There was some internal sniping between the Dutch, too.

A mentally and physically drained Cruyff could not rediscover his spark. He created several chances when restored to a forward position after the break, but nothing would go in for Michels' team.

"When it was all over, of course, there was a great feeling of disappointment," wrote Cruyff. "You know you're the best in the world, but you haven't won the prize."

Johan Cruyff meets Queen Juliana with coach Rinus Michels and the rest of the Dutch squad

Back in the Netherlands, the squad were greeted like heroes with a reception at the Royal Palace and celebration on the Stadsschouwburg balcony in Amsterdam. Cruyff later wrote that he got over the disappointment of losing the final quickly.

"Much more important was the vast amount of positivity and admiration for our play that our performances had generated all over the world," he said.

"We had set an example for billions of people. We had also given hope to all the players who, like me, weren't big or strong. The whole philosophy of how football should be played was adjusted during that tournament."

It also changed his individual status. Cruyff had already been twice crowned the world's best but admitted he did not feel famous until that tournament. When it was over, he was a global superstar and later that year won his third Ballon d'Or in four seasons.

"Cruyff was an optimal player," said Wenger. "In every situation he found the optimal solution. He had the tools to realise it. The point of his decision making was exceptional.

"You always felt he was a class above everyone on the pitch. There are few players like that. He had that elegance, you wanted to look like him on the football pitch."

But 1974 would be his one and only World Cup. Cruyff helped the Netherlands qualify for the 1978 tournament in Argentina but made a decision not to play and would not go back on that, later suggesting it was because of a kidnap attempt at the family home in Barcelona.

In many ways, it added to his legend.

Cruyff, in his four weeks on the global stage, was a playmaker-come-coach who gifted the sport a new philosophy. He left a legacy that transcends a flick, a touch, a goal, even a turn - one that has survived long beyond the last tying of his boot laces and donning of the lucky number 14 shirt.

Bibliography

Johan Cruyff: My Turn, The Autobiography

David Winner - Brilliant Orange: The Neurotic Genius of Dutch Football

Auke Kok - Johan Cruyff: Always on the Attack

BBC World Cup icons series