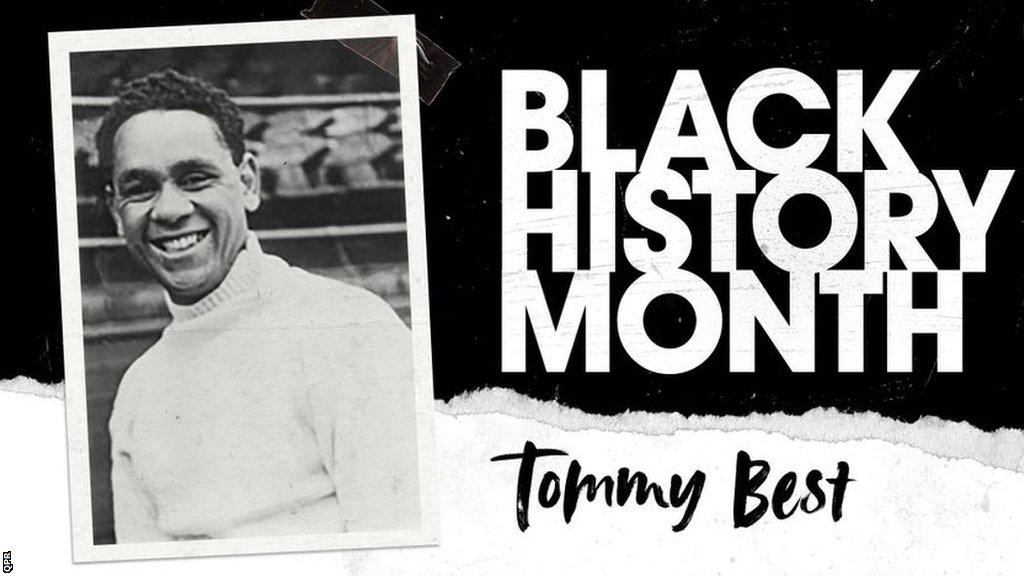

Tommy Best: Wales' forgotten black football pioneer

- Published

WARNING: This article contains descriptions of racism and other offensive and discriminatory language and behaviour.

There was nothing particularly remarkable about the game that October afternoon.

At least not according to those that chronicled West Bromwich Albion's win over a Cardiff City side still finding their way in the Second Division.

Among the words hurriedly filed back from the Hawthorns for that evening's late newspaper editions, there had been sparing mentions of the Bluebirds' new signing whose shot was so hard it punctured the ball.

But that was not out of the ordinary for Tommy Best, the centre-forward with a reputation for a powerful strike.

What was different was that Tommy Best was black.

What was significant was that, on 30 October 1948, Best had become the first black player to wear a Cardiff shirt.

But his journey to this point was not one made from within a city already established as a cultural kaleidoscope.

Because what remains remarkable is Best's story, one of a boy from Milford Haven who went to war and came back a footballing pioneer.

The tale of a South Wales derby hero who broke barriers in Wales, Northern Ireland and even London.

And yet, 75 years on, a story seemingly overlooked.

Perhaps it is not surprising given it was not acknowledged at the time.

"It wasn't recognised as the milestone it was," notes Richard Shepherd, a Cardiff City historian.

Nor, he says, was there any particular fuss made when Best, at the age of 27, completed his £7,000 move from Chester 15 days earlier.

Cardiff, after all, was a city where the burgeoning Tiger Bay had seen as many as 50 different nationalities establish communities by the time Best was born in December 1920.

It would have been a different story in Milford Haven, 100 miles west of Cardiff's dock area melting pot.

"If you look at the census from that time, more than 99% of Milford Haven would have been white so Tommy and his four siblings would have stood out," says Bill Hern, co-author of the book Football's Black Pioneers.

The son of Barbadian steam ship engineer Thomas and Welsh-born Gladys, Tommy had played football only locally; the outbreak of war had not scuppered any hopes of a career in the game as much as sparked them.

Joining the Royal Navy and serving on the minesweeper HMS Gloman, the ship was damaged by a raid while docked in Belfast.

It was to prove fortuitous and fateful for Best, a chance that created a career.

A Dublin side - Drumcondra - were a man short for an inter-city cup tie against Belfast Celtic. Somehow - and it's not quite clear how - Best was encouraged along by his chief petty officer, and then invited to play. He duly scored.

It was enough to knock-out the top-tier Belfast team, earning Best a contract and the status of being the first black player to play professionally in Irish football.

It also earned him a nickname that his family say he loved, but nevertheless says something about the time: Darkie Best.

"I suppose it was a novelty seeing a coloured man playing in green and white," Best told the Belfast Telegraph in 2006.

"I was never subjected to racial comments by anybody - team-mates, officials or supporters. I looked upon Belfast as my second home."

It is a sentiment he echoed to the three children from his 50-year marriage to Eunice.

"He loved that nickname," says daughter Jenny Hotchkiss. "He didn't see anything in a colour, he saw people as people.

"I'm sure there were times he would have been upset, but he wouldn't show it.

"I think he just loved football so much he wouldn't care what people wanted to say. He was a big, powerful man, but more than anything he was full of love.

"He could just ignore words. His brother was different; he would get into trouble fighting when people would call certain names. Dad didn't speak about that. Perhaps he just ignored it."

Not that the concept of racism or prejudice was lost on Best.

When a posting to Australia prompted his exit from Belfast Celtic after a season, Best played for Queensland side Thistle FC. He was said to have disliked Australia because of the treatment of Aboriginal people.

Eventually, he would return home and play for Milford before a trial at Chester saw him move to the Third Division North club in 1947. He had become the first black player to feature in a league game for the side.

With 14 goals in the 30 games he played in his first season, Leeds, Blackburn and Blackpool were all mentioned as possible suitors in what would be a record sale for Chester.

He chose Cardiff, doubling his wages, but it was the lure of returning to Wales that was the decisive factor.

Pictures in the South Wales Football Echo show a besuited Best smiling as he signed his contract under the eyes of manager Cyril Spiers. Best's considerable size was referenced, deemed a "heavyweight striker" weighing in at 14 and a half stone despite just a 5ft 10ins frame.

The colour of his skin was not mentioned, not at least until after his first appearance for Cardiff's reserves where he was said to "know all the arts of football".

It added: "Best, though coloured, is a Welshman."

It was not until the end of the season that he made his mark, impressing particularly in a game against Tottenham Hotspur and then scoring his first goal in a 4-0 March win over West Ham United, the first of four in four games.

"Rarely has one player done so much to cheer so many spectators and enliven a rather tame game until the closing minutes as did chocolate-coloured Tommy Best, City centre-forward, at Ninian Park," read one London report the day after the West Ham fixture.

Such terms would follow him through his career, certainly in press reports outside of Wales.

At QPR - where he also became the club's first black player - fans were said in one newspaper column to like chocolate, "not because of a sweet tooth…but the club's new inside man, Tommy Best. For that is the nickname that has been stuck on this brilliant coloured boy since his arrival at Shepherd's Bush".

In another report towards the end of his career in non-league, when his weight had even crept up to 17st, the writer - calling Best 'easily the outstanding player" - said he was still recognisable due to his skill and "his dusky face and flashing smile".

As repellent as it would be considered now, Best appeared to excuse the language as coming from a place of affection.

"It's what we could consider openly racist," says Bill Hern. "It was rare for the press not to refer to colour in whichever way you could think.

"And there would have been a scale, certainly from the terraces, to words that would horrify us now. We might not have many records of it, but undoubtedly he would have had to suffer it."

The club historian at Hereford - where Tommy would later play and settle with his family - recalls the same story of abuse that Best recounted to his children.

"He said it could be pretty bad at times, but he told me the worst he ever had was in a game at Merthyr where there had been bananas thrown and the monkey chants," recalls Ron Parrott, who became a friend of Tommy in later life.

"But he swore it didn't upset him. As he told me about it, he leaned to me with a wicked glint in his eye and said the more they did it, the harder he tried."

His second season at Cardiff begun as his first ended, with a flurry of goals. Tributes flowed from the news pages as he scored five in his first eight games, including the only goal in a 1-0 derby win over Swansea in front of a then-record 57,510 at Ninian Park.

His form did fade and, after injury, Cardiff's struggles saw them consider new attacking options.

Best moved to QPR as the Bluebirds looked to balance the books in the early days of escalating transfer fees, becoming a popular figure in his year in West London - described as giving an 18-year-old John Charles of Leeds a torrid time on his Loftus Road debut - before heading to Hereford.

But it was his Cardiff prime where Best wondered if he had done enough to realise a dream of playing for Wales, following in the footsteps of Eddie Parris who had become the national side's first black player in 1931.

There had been a time when a schoolmaster had told Best he had little chance of selection when going for a Welsh Schoolboys trial, but this was different as the forward impressed in the second tier of English football.

"He said he was called into the manager's office at Cardiff and said he was being considered for Wales," says daughter Jenny. "He thought he was going to be called up. He was overlooked and that hurt him. It would have meant everything."

In an interview given to the Western Daily Press in 1998, Best said: "I can only assume it was because of my colour. You have to remember that black players were a rarity then, and I'm forced to the conclusion that I was the victim of prejudice."

Best may have simply been unlucky; in his position stood Trevor Ford, one of Wales' greatest ever strikers who, despite suggestion of injury at the time of Best's best performances, did not miss a game in that period.

"I'm not totally convinced because of Ford's presence and because Tommy never did play First Division football, but we might never know for certain," adds Hern.

"But it does show that he was conscious of the colour of his skin."

And proud, just as he was of his career.

Best lived to the age of 97, suffering with dementia before his death in 2018, but did manage to enjoy trips to his former clubs Belfast, Chester and Hereford.

"Even when he was in hospital, when he didn't really know who we were, he would still be able to tell all the nurses about his career and reel off the clubs he played for," daughter Jenny says.

"We would stop in a wheelchair and next to someone and he would say, 'Hello, I'm Tommy Best, did you know I played for Cardiff or Hereford or QPR'."

Achievements in itself, but as a footballing pioneer, it is something else. Remarkable even.

"He would have been a star, I'm sure," she adds. "Perhaps it's a surprise more people don't know his story. I wish it could have been recognised more.

"I'm not sure people really realise what he and other black players of that era would have gone through."

If you have been affected by issues raised in this article, there is information and support available on BBC Action Line.

BLACK MUSIC WALES: The artists who pioneered black music in Wales

WALES' HOME OF THE YEAR: Which home will be crowned the winner?