Why xG can't always tell us how good a team really is

Morgan Rogers' free-kick goal for Aston Villa against Leeds had an xG of just 0.11

- Published

If you look at the expected goals (xG) for the Premier League results last weekend, you would probably be thinking the statistic is a load of rubbish.

Of the 10 matches, the xG score for each team matched the result in only three fixtures. For instance, Manchester United (2.27) lost 0-1 at home to Everton (0.16).

Yet xG is not going to take into account that Everton had a man sent off or that they played with their backs to the wall for most of the game.

It can tell us that United did not create many big chances from their 25 shots, Mason Mount (0.44) and Luke Shaw (0.38) being the best of them.

If the xG is so wildly out, is it time to stop giving it so much prominence? Not so fast, perhaps.

In week 11, the xG matched seven results, and in week 10 it had eight correct.

Since 2021-22, xG has an accuracy level of 59% and it is at 57.5% this season, which is a one, or two-result swing from being on trend.

Most importantly, xG is not trying to be a barometer of individual results, rather a metric which assesses every chance a team creates and how effective they are at converting them.

Aston Villa, Sunderland and Tottenham would be in the bottom four if their results were based on xG , yet in the real world actual goals have them in fourth, seventh and ninth respectively.

Villa have been exceptionally good at scoring from distance (more on this later), while for the other two teams goalkeepers Robin Roefs and Guglielmo Vicario have been excellent at keeping out high-quality chances from the opposition.

So, you might ask, what is the point of even measuring xG in a game?

Here's a better way to think of it: If you leave a game saying "I can't believe we lost that" or "if we keep playing like that we'll be alright" then you will most likely have a higher xG than your goal return.

If you're saying "I can't believe we won that", then it's going to be a low xG.

The idea is, eventually, a team should start performing to their xG, good or bad. That cannot take into account various issues about general player and team form. Just look at Liverpool: on xG this season, they should be fifth rather than 12th.

So, what influences xG? And is it really a reliable way of assessing a team's performance?

More set-piece goals with higher difficulty

Taking a closer look at tactical trends this season, a few key methods of chance creation stand out.

There is an increased focus on exploiting set-pieces including corners, free-kicks and throw-ins.

If we think of set-pieces as mini-games that can be choreographed beforehand, it is easy to see why the likelihood of scoring from these situations in reality would exceed the predictions of an xG model.

Opta's xG model takes into account many factors including distance from goal, goalkeeper position, the clarity the shooter has towards goal based on the positions of other players, the amount of pressure they are under from the opposition defenders and shot type.

Set-pieces often result in shots being taken in crowded penalty areas with the scorer under some pressure meaning xG is likely to underestimate the proportion of well-worked moves resulting in goals.

If a Premier League team is able to manufacture a shot from a set-piece, it is likely that their pre-planned routine will have worked. Irrespective of the shot location and player position, this puts the attacking team at an advantage compared to the unprepared defending side.

What does xG tell us about how Premier League teams have started the season?

- Published15 October

Should Spurs be worried about their attack?

- Published2 days ago

What is xG in football and how does it work?

- Published26 September

xG does not factor in how good a player actually is

Opta's xG model assumes 'the average player' is taking the shot. It therefore underpredicts the likelihood of goals when better players are taking the shots in zones that suit them.

In our set-piece example, it is fair to assume that teams will create routines that aim to get their most dangerous scorers in shooting positions, resulting in more goals than the average player would score.

This idea was confirmed in a recent study that found Opta's xG model overpredicted the number of goals teams lower down the table would expect to score, while underpredicting how many goals teams near the top of the table (with better players) would.

Shots from distance may give a false impression of performance

A second trend this season has been teams creating shots from in front of defences that have dropped deep.

Spurs have massively overperformed their xG this season and have scored many goals in this way. The same can be said of Aston Villa, who are high in the table despite creating the worst-quality chances.

By attacking at speed or carrying the ball towards the byeline, teams are able to push defences closer to their own goal resulting in attackers finding themselves in space further out.

We know xG heavily factors in shot distance and the clarity a shooter has based on defenders between them and the goal so these situations are lower xG chances. These chances however result in an unopposed shot centrally resulting in a goal frequently.

Direct free-kicks

The last 'low xG' method of scoring that has paid dues for teams this season has been scoring directly from free-kicks.

The number of direct free-kicks a team wins and the likelihood of putting these away from distance mean they do not contribute much to xG tallies. The average player is unlikely to score from these situations.

For teams with strong free-kick takers, overperforming xG from set-pieces is a pattern we have seen over many years.

xG overperformance in practice

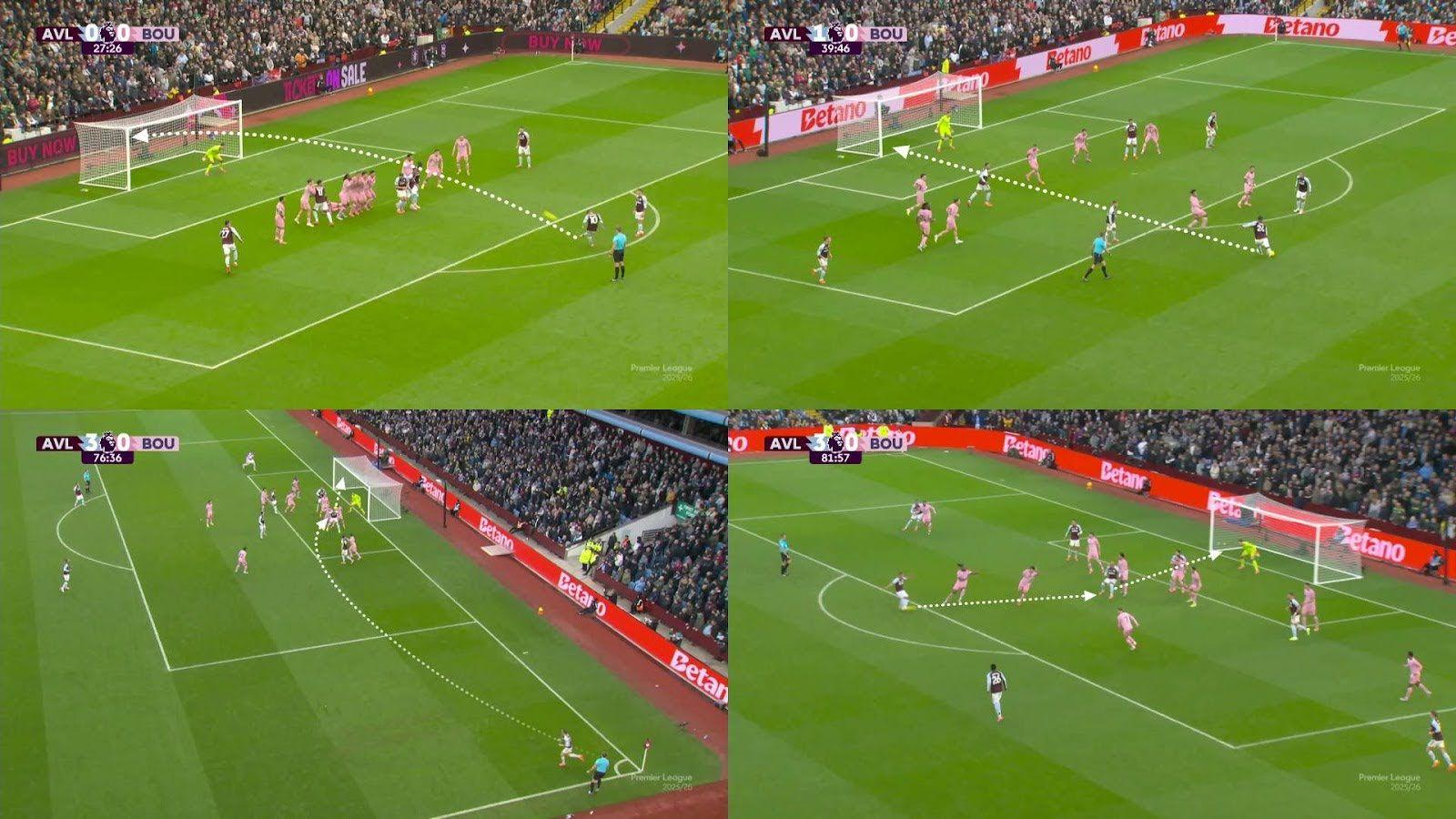

Aston Villa's four goals against Bournemouth all came with a very low xG

Aston Villa have scored 4.06 goals greater than their xG this season, more than every team bar Spurs (8.84) and Burnley (5.26). Villa's 4-0 win against Bournemouth this season illustrates what we have discussed well.

Despite scoring four goals, Villa's xG was just 1.88 - lower than Bournemouth's 2.01.

Villa were willing to take numerous shots from distance with their capable ball-strikers taking advantage of the space in front of Bournemouth's defence.

The first goal was a 0.14 xG free-kick by Emiliano Buendia from the edge of the box.

Amadou Onana then scored a 0.04 xG shot from outside the box under less pressure through a crowd of bodies.

Villa's third was a 0.10 xG header from Ross Barkley from a well-worked corner, and the fourth goal was a corner routine that found Youri Tielemans at the edge of the box. Tielemans' shot was directed home via a 0.12 xG Donyell Malen deflection.

The four goals came from a total xG of 0.4 including two shots from distance in front of a defence that had been pushed back, and two set-pieces.

So, is xG still useful?

Although xG might not tell the whole story for individual games, over the course of a season it tends to even out well.

Last season, the four teams that won the most games on xG finished in first, second, fourth and fifth place.

The tactical trends mentioned, although partly sustainable, occur less often per game when compared to the number of open-play chances from teams that dominate. They also require top individual quality to execute well given the difficulty.

If a team is consistently getting into good shooting positions close to goal over a season, it is safe to assume they will finish in a good league position.

The great thing about football is that on any given day, moments and individual quality can help any team win. And xG is not trying to take that away.

Related topics

- Published17 October