Tarmac and tiaras - the magic of the Monaco GP

- Published

Under Mediterranean skies, in a tiny principality where modern skyscrapers and beaux-arts villas fight for space as they tumble down a hillside, the faces of Formula 1 converge.

For some, Monaco is a kind of pilgrimage, a chance to worship their sporting gods. For others, the god is mammon, the sport incidental. In reality, the one cannot exist without the other.

Up in Casino Square, the grand prix's most famous location. In front, the lavish rococo towers of the Casino itself; to the right the Hotel de Paris, a place so synonymous with the grand prix that Jackie Stewart still stays there every year, 41 years after he last won the race.

Between them, a narrow ribbon of asphalt, essentially unchanged since the first race at Monaco 85 years ago.

Blur your eyes, and little has changed up here since those days, since the Monaco of Somerset Maugham.

Fernando Alonso tackles the infamous stretch of road in front of the Hotel de Paris in 2007

Focus again on why you're here, and the 21st century comes rushing back.

Until the late 1970s, this was the place to watch F1 cars in action in Monaco.

As the cars exited the right-hander that takes them in front of the Casino, the crest in the road would flick them sideways, the driver fighting the wheel to retain control. Cars at 30 degrees or more, grand Riviera hotel in the background - Monaco in a single frame.

Now, the predominance of aerodynamics means the cars have to stay more or less straight. If the romance of this spot remains, some of the overt drama has gone.

Cross the track, over one of the blue metal bridges that form the maze of walkways around Monaco during the grand prix. Stroll through subtropical gardens towards Massenet, the corner that leads into Casino Square.

To the left, a couple of hundred feet below, another aspect of the 'new' Monaco.

As ever, the harbour is full of boats, but they seem to get bigger with each passing race.

Turn away from the harbour, to the right. The cars pop up over a brow, back into vision after the steep climb up Beau Rivage from Sainte Devote, the start of the lap.

As soon as they're in sight, the drivers brake down in no time at all from 180mph to 100, fighting to force their squirming cars into the corner, hugging the barrier all the way into Casino Square.

On the other side of that barrier, a row of high-end designer shops that require customers to ring a doorbell before they are considered acceptable and let in. Above them a polite row of privileged spectators, many dressed in clothes that could have been bought from those very shops.

Back through the gardens, down some steps, into a lift, descend to sea level. It opens into a marble corridor. A blast of noise and vibration. Follow it. Up a staircase. At the top, sensory overload awaits - the famous Tunnel.

You don't so much watch Formula 1 cars here as feel them with your whole body.

In a confined space, with cars doing 180mph no more than two metres away, the violence is overwhelming - the noise deafening even through noise-cancelling headphones, no chance of hearing the BBC commentary in your ears; the blast of air being forced aside so strongly it literally pushes you back.

It's an experience unlike anything else, one not to be missed. But it's too uncomfortable to stay here long. So head down towards the Nouvelle Chicane, the bump in the braking zone that pitched Sergio Perez's Sauber into the wall in 2011 now smoothed out.

For the first 55 years of the Monaco Grand Prix, the chicane was a fast, testing left-right kink. But after one too many accidents, it was tightened in 1985. It's now clumsy and slow, the cars clattering and bouncing over the kerbs, wheels spinning on the exit as they head off down to Tabac, where Monaco at its best begins.

For Jenson Button, the Swimming Pool section is "crazy"

In this most elitist of places, where millionaires move to dodge taxes, where Ferraris seem more common than Fords, there is a democracy to Tabac. The biggest grandstand in Monaco affords a view of one of the greatest pieces of asphalt in the world.

When the F1 cars are on track, the boats are moved away from the quayside. It's for safety reasons, but it feels like a statement of priorities.

Approaching through dappled shadows under trees, the drivers head for Tabac's fast left-hander. Following it, the even faster, 150mph chicane at the Swimming Pool.

Stand on the harbour front, between the two corners and look back in the direction from which the cars are coming.

The barrier on the outside of Tabac is in two parts - the first part stopping, a second overlapping behind, the gap to provide access for safety marshals.

The cars are dancing on the edge of adhesion, the drivers turn in blind on a line that aims for the extra space provided by the offset of the walls.

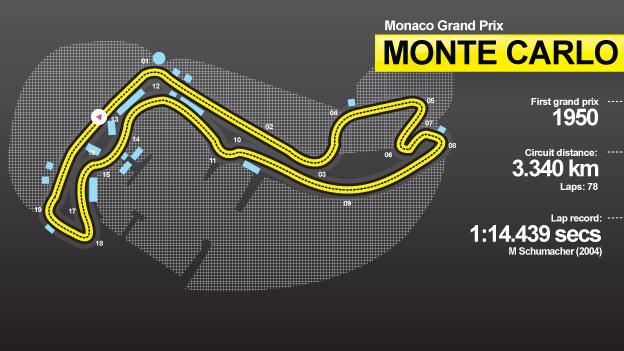

Monaco Grand Prix

Get it right, the reward is tenths of a second; get it wrong, you hit the wall at 130mph.

At the Swimming Pool, the stakes are even higher. Twenty years ago, the cars skimmed between concrete walls here. That was deemed too dangerous. The walls were moved back a little, low kerbs now mark the extremities of the track.

The wall, though, is still key - it's what the drivers aim for, relying on the sliding of the car on turn-in to carry them towards the perfect line between the kerbs.

Button: "You turn in thinking you're going to hit the apex - as in, the wall apex. When you get there you don't hit it because you're carrying such high speed. It's an unusual couple of corners, but a lot of fun. I think we all enjoy it."

From the outside, fun isn't the word. It's awe, the skill and bravery almost incomprehensible. "It's just madness driving around here," Button says. "In a good way."

Out in the harbour, people are sunbathing on multi-million-pound boats, cocktails in hand, some oblivious to the show just a few yards away.

That's one side of Monaco. Massenet, Casino Square, the Tunnel, Tabac, Swimming Pool; they're another. They co-exist, interdependent, the one providing the money that makes the other possible.

This feature was originally published in 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published24 May 2012

- Published24 May 2012

- Published18 May 2012

- Published13 May 2012

- Published13 May 2012