Italian GP: The magic of Monza and Ferrari's home race

- Published

- comments

In Italy, Formula 1 means Ferrari. And Monza is where the relationship is consummated.

The home of this weekend's Italian Grand Prix, Monza is a race track like no other. This is no featureless former aerodrome, like Silverstone, or characterless monument to a government's ambition, like so many of F1's newer circuits.

Monza is achingly beautiful. And it is steeped in an atmosphere born of a rich history almost as long as that of motorsport itself.

Located in a royal park and nestled in dense woodland, Monza has an ambience unmatched by any rival.

Cool, misty mornings in early September Lombardy give way to hot, sunny days. Protected trees cast moody shadows. The light is a golden late-summer haze, the backdrop the foothills of the Alps.

Out there in the woods, the ear-splitting scream of an F1 engine at 18,000rpm gives way to a silence punctuated by birdsong.

Leave the pits and walk down to the first corner, past the old banking - last used for F1 in 1961, its crumbling surface dotted with weeds, so steep you can barely walk up it - and look back up the pit straight. The view - of the old grandstand, the historic timing screen, the heat haze - is much the same as it has been for decades.

Stand there, close your eyes, sense the ghosts, and feel transported back through 90 years of triumphs and tragedies, through the makings of a sport.

"Monza is a very special place," says Pino Allievi, a veteran columnist for Italy's leading sports newspaper, Gazzetta dello Sport, who has covered F1 since the 1970s. "In going there, you go through a tunnel with history. It is different from any other circuit. There is a magnetism you don't get anywhere else."

This famous old autodrome has existed since 1922. It's the world's second oldest permanent race track still in active use, after Indianapolis in the United States.

For much of that time, it has been associated strongly with a name that will be at the centre of things this weekend, as it has been since F1 began in 1950 - Ferrari.

The unique blend of glamour, speed and aesthetics represented by its cars resonates throughout the world, but nowhere more so than in Italy, where the famous racing and sports car constructor is almost a way of life.

It has been so for nearly a century. Enzo Ferrari, the legendary founder of the marque, raced for Alfa Romeo in the 1920s and 1930s, alongside the greats of the era such as Tazio Nuvolari and Antonio Ascari. He made the name Ferrari popular before he set himself up as a manufacturer of road and racing cars in his own right in the 1940s.

One of Ferrari's many visionary qualities was to see the value of public relations long before it became a modern obsession, and he used it ruthlessly. He was, for example, the first to set up his company's own magazine - a lead nearly all exclusive car manufacturers have since followed.

The relationship Ferrari built with his people has been passed down through the generations. As Allievi puts it: "As with my grandfather, then my father and now me. Since the early 20th century, everyone has known the name of Ferrari."

Elsewhere in the world, F1 has opposition from tennis, cricket, golf, rugby, cycling and any number of other sports that battle for recognition in the wake of the juggernaut that is football. But in Italy, there is no competition - there is football, there is F1, and then there is everything else.

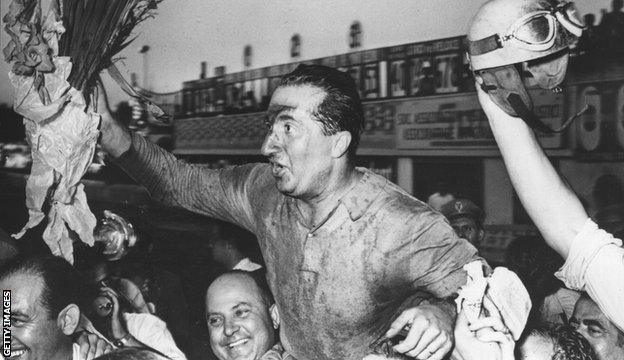

Ferrari driver Alberto Ascari is hoisted aloft by fans after winning at Monza in 1951

Monza is where they come to perpetuate the link, Ferrari the medium through which they do it.

The track has hosted the Italian Grand Prix since it was built, with very few interruptions. The first such was in 1929 and 1930, following an accident in 1928 in which Italian Emilio Materassi crashed his Talbot opposite the pits, killing himself and 27 spectators. Racing at the track was stopped for three years.

The only other breaks have been for the Second World War and the anomalies of 1937, when the race was held in Livorno, and 1980, when Monza was being refurbished and the Italian Grand Prix moved to the Imola track near Bologna. Imola went on to become the home of Italy's second race, the San Marino Grand Prix, from 1981 to 2006, and is where Ayrton Senna was killed in 1994., external

In its long history, Monza and its spectators have seen a lot. All the great drivers have raced there, and many have lost their lives.

The legendary five-time champion Juan Manuel Fangio was lucky to survive a crash there in 1952 in which he broke his back, but won on his next appearance a year later.

In 1961, the German Ferrari driver Wolfgang von Trips, on the verge of winning the world championship, was involved in another tragedy, when he collided with Jim Clark's Lotus and flew into a crowd of people on an embankment, killing himself and 14 others.

Nine years later, another man on the brink of a world title was killed - Austrian Jochen Rindt, whose Lotus crashed approaching the Parabolica corner, almost certainly because of suspension failure. A few weeks later, Rindt was crowned F1's only posthumous world champion.

Michael Schumacher waves goodbye to the Monza crowd after announcing his retirement in 2006

Into the early 1980s, 150,000 people or more would flock to Monza every year to worship at the altar of Ferrari and its drivers. Many would erect their own rickety viewing stands - free-form scaffolding structures were to be found dotted throughout the woods, decorated with home-made banners.

Those structures have long since been banned, swept away in the tide of uniformity forced on F1 by its iron-fisted ruler Bernie Ecclestone, and the safety requirements of the modern age.

At the same time, the famous Italian fans - the tifosi - are not as excited by the modern-day heroes of F1 as they were by their predecessors.

The biggest ever Monza crowd, Allievi says, was in 1982, when the Italian-born American Mario Andretti took pole position for Ferrari as a stand-in for the crowd's last great hero, Gilles Villeneuve, who was killed at the wheel of his F1 car earlier that year.

Then, 120,000 turned up just to watch practice. This year, Monza's owner, the Automobile Club of Milan, is expecting about 80,000 to attend Sunday's race. Still a large number compared to many races, but not what it was, even though F1 has retained its popularity in Italy with those who watch television and read newspapers.

"People feel more distant from F1," Allievi says. "They feel it's all business, that it's too complicated, and that Ferrari have not had any charismatic drivers since Niki Lauda and Villeneuve."

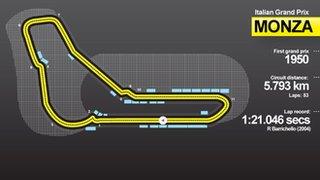

The Monza circuit is a good challenge for the drivers and braking stability from high speed is a crucial requirement

That is despite the five consecutive titles Michael Schumacher won for the team from 2000-2004, and current driver Fernando Alonso's heroic efforts to fight the domination of Red Bull.

"Schumacher was respected tremendously, but not particularly loved," Allievi says. "And Alonso is viewed in the same way now."

Nevertheless, those who do turn up help make Monza a truly special occasion.

The crowd - though perhaps more distant than in the past - cheer and chant for the Ferrari drivers just as they always have.

And a win by Alonso on Sunday would be greeted in the same way as a victory always has, with a track invasion by thousands of people, and the winner spraying champagne on to the multitude below.

For the tifosi, there would be no more fitting climax to four marvellous days when old gods are worshipped, gods of racing rather than commerce, at a circuit that is a cathedral to speed.

- Published5 September 2013

- Published5 September 2013

- Published5 September 2013