Bernie Ecclestone: F1 chief has never been more powerful

- Published

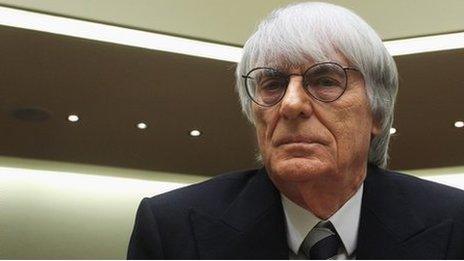

As Bernie Ecclestone made his unintentionally comedic entrance to the High Court on Wednesday, it would have been easy to come to the conclusion that the old dictator may be starting to lose his grip.

Discombobulated by a revolving door, spat back out on to the street and unable to find his way back inside as reporters and television cameras looked on, Ecclestone briefly looked every one of his 83 years.

The legal cases he is facing in London this week and, perhaps even more seriously, in Munich early next year certainly count as serious threats to Ecclestone's position as the chief executive - and overlord - of Formula 1.

If he loses in court, and is convicted of corruption and/or bribery, it is hard to see how he could carry on in that role. Yet behind the scenes in the sport he has made his personal fiefdom over the last 40 years, Ecclestone has, in the words of one leading team principal, "never been more powerful".

This is a time of major political change in F1, and Ecclestone has used the uncertainty to vastly strengthen his position - and by extension that of whoever takes over from him in the future as the representative of the commercial rights holder (CRH).

Bernie Ecclestone's bizarre High Court entrance

Over the last 20 years or so, F1 has been run by a combination of the teams, the CRH and governing body the FIA. The CRH made the money, and the FIA made the rules, with input from the teams and the CRH.

But an apparently subtle change over the last few months has shifted the balance of power dramatically, significantly weakening the position of the FIA under its president Jean Todt and strengthening that of Ecclestone.

Todt has, in the words of one senior figure, "auctioned off the FIA's ability to make the rules".

The process has also effectively disenfrachised the smaller teams and concentrated influence in the hands of the wealthy few.

It has come about because Todt wanted more money from Ecclestone so the Frenchman could carry through his plans to reform aspects of the FIA.

Ecclestone was reluctant to give it to him, and they compromised on an arrangement whereby the FIA increased the F1 entry fees for the teams, adding in an extra levy per championship point scored.

This has given Todt an extra £40m a year to play with. In return, he has agreed to a change in the rule-making process that appears on the face of it to strengthen the FIA's influence, but to those who understand how things work in F1, does the exact opposite.

Previously, changes to the rules were discussed in two working groups made up of experts from the teams and the FIA - one for technical matters and one for sporting matters.

Their recommendations were passed to the F1 Commission, a group of 26 members, comprising representatives of the 11 teams, eight race promoters, the FIA, Ecclestone and suppliers of engines, tyres, fuel and sponsors. Eighteen votes are needed for a vote to pass.

In turn, the F1 Commission sent its recommendations to the FIA World Council, the governing body's legislative arm, which Ecclestone and Ferrari also sit on. This has tended to be a rubber-stamping process.

Under the new system, the technical and sporting working groups have been disbanded and replaced by a 'strategy group', comprising six teams. Five teams are permanent members - Ferrari, Red Bull, McLaren, Mercedes and Williams - and the sixth seat is given to the most successful current team not in that group. At the moment, that is Lotus.

The strategy group can seek advice from any quarter it likes, but there is no obligation for it to seek the general approval of the teams in a round-table forum such as the technical or sporting working groups.

In terms of decision-making, the six teams on the strategy group have one vote each, while Ecclestone and the FIA have six each, with motions passed by a simple majority.

On the face of it, then, the FIA has significant influence. But in reality it does not work like that. Because any motion only needs 10 votes to pass, Ecclestone only needs four teams to support him to win any vote on the strategy group.

Red Bull, who are extremely close to him, are considered pretty much a given, and to get three more "straightened out", as one senior figure puts it, is child's play for a man of Ecclestone's influence. So, in reality, Ecclestone effectively controls the strategy group.

The same goes for the F1 Commission, where the eight race promoters, tyre supplier and sponsors, along with the majority of the teams, again weigh things in Ecclestone's favour.

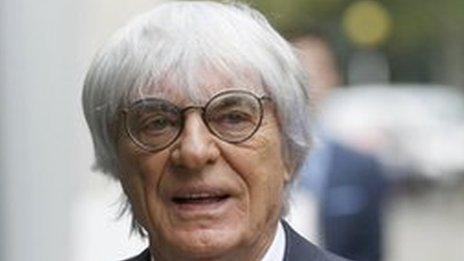

At the High Court, Ecclestone denied making corrupt payments to a German banker

The teams not represented on the strategy group have grave concerns about being excluded, and one of their biggest worries at the moment surrounds discussions about the introduction of 'customer' cars.

It is well known that several of the smaller teams are struggling with the costs of F1. One solution being talked about is, rather than them being forced to design and build their own cars, to allow them to buy second-hand cars from the big teams.

At first glance, this sounds like a good idea. It saves the small teams millions of pounds by allowing them to buy off-the-shelf cars and generates extra income for the big teams.

But the potential downsides are much more serious. The small teams say it will deprive them of their core businesses and force them to lay off hundreds of people - and may eventually as a result force them out of business. It also reduces the diversity of the F1 grid, removes a core tenet of the sport, and potentially causes problems that could undermine the future of the sport.

After all, if customer cars were part of F1, who after a season like 2013 would want to buy anything but a Red Bull? And if in the future, say, two of the smaller teams had year-old Red Bulls which happened to be faster than a new Mercedes, how long would Mercedes want to stay in the sport?

Whether this will happen or not, no-one is sure. But one thing can be counted on. However Ecclestone wants F1 to change in the future, he has created a system that makes it very much easier for him to get his way. Assuming he can survive these court cases, that is.

- Published5 August 2014

- Attribution

- Published6 November 2013

- Attribution

- Published17 July 2013

- Published15 May 2013