David Coulthard column: F1 will never eliminate its inherent danger

- Published

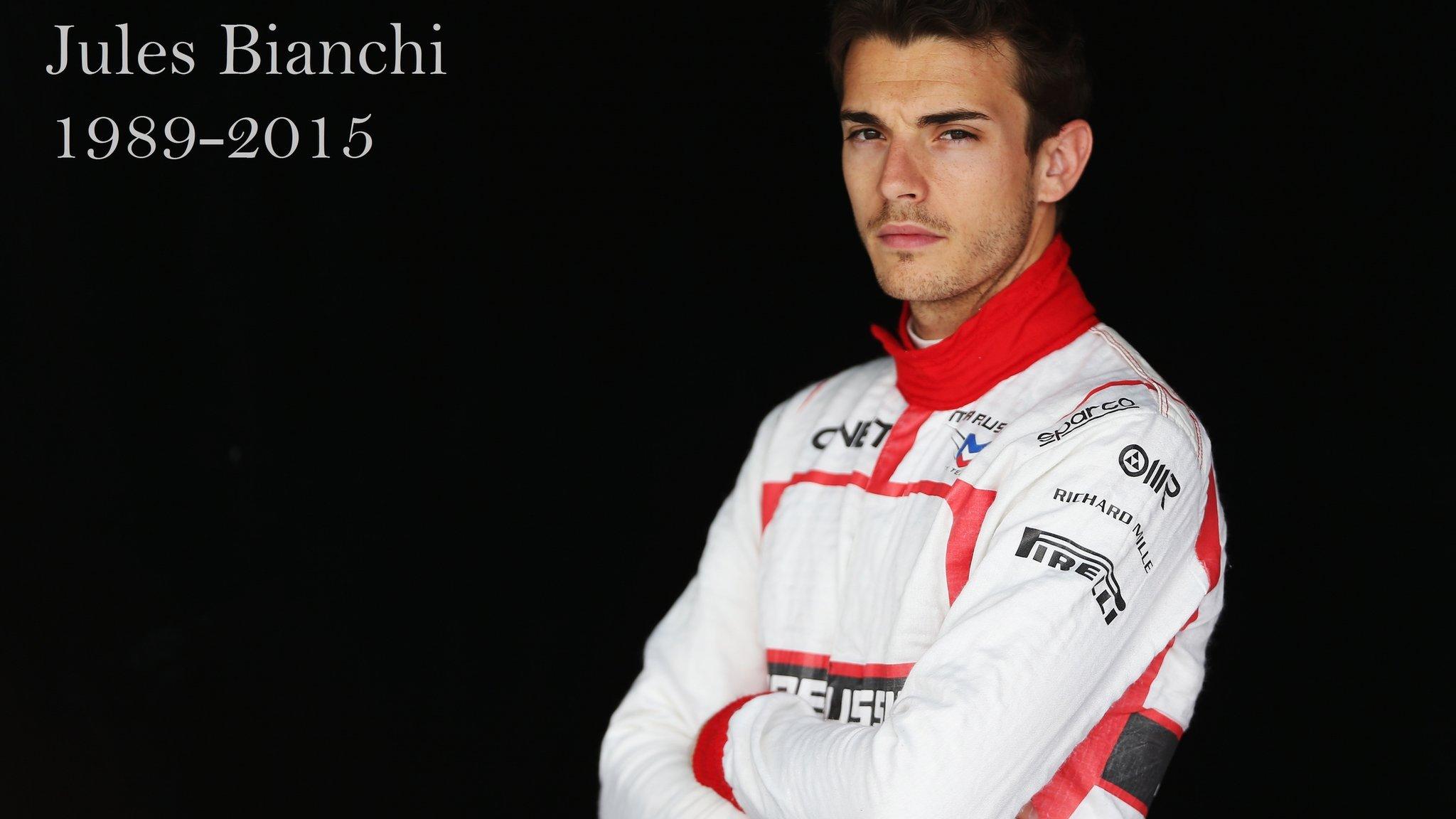

Formula 1 is no stranger to tragedy, and the death of Jules Bianchi, external from injuries sustained in a crash in last October's Japanese Grand Prix is a reminder that danger is never far away, however distant it might appear.

Over the last two decades, F1 had become accustomed to seeing drivers walk away or emerge uninjured from very big accidents, such as Robert Kubica's barrel roll in Canada in 2007, external or Mark Webber's somersault in Valencia in 2010., external

That is testament to the work done to improve safety following the terrible events of the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, at which Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger were killed in two separate accidents and three other serious incidents provided a wake-up call for everyone involved.

The lessons of that weekend in Imola have never been lost on those in positions of influence in F1.

Any incident such as that inevitably leads to a period of introspection, and further changes have been made as a result of Bianchi's tragic loss.

How F1 reacted to Bianchi crash

In many ways, what happened to Bianchi can be described as a 'freak' accident. The odds against him going off, in a sector of the track covered by double waved yellow flags - the most extreme form of caution before a race stoppage - and hitting a recovery vehicle, external must have been huge.

There were even more unusual circumstances in the most serious accident since Senna's prior to Bianchi's, when Felipe Massa suffered a fractured skull, external when he was hit on the helmet by a suspension part that had come off another car in Hungary in 2009.

Read more on Bianchi's death | |

|---|---|

In both cases, though, lessons have been learned.

Helmets have been redesigned and strengthened as a consequence of Massa's crash.

And following Bianchi's accident, two key changes have been made for safety reasons. One was the addition of extra strengthening around the cockpit. The other was the introduction of a system called the virtual safety car, external under certain circumstances in races.

Bianchi suffered his injuries when he collided with a vehicle that had been sent out to recover another car.

All the correct procedures were followed at the time, but Bianchi nevertheless lost control of his car and went off the track.

The virtual safety car takes away from the drivers the decision of how much to slow down to be safe in such circumstances. When it is deployed, which typically would be in exactly the situation in Japan last year, the drivers have to drive to a 'delta' time on their dashboard.

That means the chances of a similar accident happening again are even smaller than they were before. Still, though, danger cannot be completely removed - even 50mph is potentially fast enough for an F1 car to aquaplane and go off the track.

The unsolvable danger

David Coulthard took over Ayrton Senna's seat at Williams following the Brazilian's fatal crash at Imola in 1994

Clearly, the biggest risk to an F1 driver's safety is his exposed head and there has been much debate about the fact that grand prix cars are open top, and the dangers that creates.

Many changes have been made in recent years to protect drivers' heads, and governing body the FIA continues to research the topic further.

There have been tests of jet fighter-style canopies and various other structures forward of the driver.

But each had major flaws and in the end the decision so far has been not to interfere with the DNA of the sport, which has always been for open-top, single-seater racing cars.

In this, there is a parallel with boxing, where the professional game continues without head protection when it is used in the amateur form.

There are other forms of motor racing where the driver's head is covered, but F1 is the pinnacle in terms of speed and challenge and that is where those who have the ability and the opportunity will always want to be.

Why drivers do it

David Coulthard says he was able to "compartmentalise the different aspects of the job" through his own accidents

No-one involved in motorsport is ever under the illusion that what they are doing is not dangerous.

Although an F1 racer had not suffered a fatality between the deaths of Senna and Bianchi, there have been several drivers killed in crashes in other categories.

Danger is an inherent part of life, and depending on your life choices you put yourself either more or less at risk.

Everyone who steps into a racing car knows that what they are doing could put their life in jeopardy, but they still choose to do it because of what it gives them back.

I got my opportunity in F1 because of Senna's death - I replaced him at Williams. I never forgot that. But, from my own point of view, I was able through my own incidents and accidents to compartmentalise the different aspects of the job.

For me, the joy and pleasure of competing and being part of a team outweighed the potential yet unknown risks of what might happen. And I suspect that is how 99% of the global population live their life.

We all know we're going to die one day, but we don't look at every footstep we take for fear of going down a sinkhole that might be about to open.

Motor racing is dangerous - it says so on the ticket

The draw of motor racing is great enough that some people will always put themselves at risk to do it - and that's not just the drivers.

Anyone who is involved in the running of a motor race is potentially in danger. During my time in F1, two marshals were killed. Despite standing behind barriers in designated 'safe' places, they were still hit by flying debris.

The same goes for spectators. Everything possible is done to protect them, but there is always the chance that something could happen.

When cars are travelling on the limit at 200mph and more, it is not possible to mitigate every risk.

Jules Bianchi 'fought to the very end', his family said in a statement

When you buy a ticket, "motor racing is dangerous" is written on it for a reason. The same phrase is on the passes you need to get into the paddock and work in F1.

Accepting that, though, is not the same as doing nothing about it. Those in positions of responsibility in the sport have sensibly and continually looked for solutions to reduce the risks.

The concept of safety runs through the rules governing the cars, which are not even allowed to venture on to a track before passing stringent impact tests.

Nowadays everyone involved in the sport has to think like that - in a way they might not have done 30 years ago or more.

And as much as the engineers who create the cars focus on performance, I do not know a single one who would ever compromise a driver's safety in their quest for extra speed.

The inherent contradiction of F1

F1 is about pushing the limits of human ability. That is a big part of its appeal to millions of people around the world.

Some people are just wired that way, to be competitive, to push beyond where most others will go.

Others watch for myriad reasons - because the racing is exciting, or because they admire what the people involved are doing, and understand what it means and - let's accept it - because they know what's at stake.

Throughout F1 there is an absolute understanding of the importance of safety, from the sport's supremo Bernie Ecclestone down.

In the 21 years I have been hanging around grand prix tracks, safety has improved considerably - to the point where people are now asking whether the sport has been sanitised so much that the perception of danger has been reduced too far.

At the Japanese GP during lap 41, Bianchi crashed into a recovery vehicle as it lifted the Sauber of Adrian Sutil

As Bianchi's accident proved, the danger is still very much there.

It happened at one of the older race tracks, in the most challenging circumstances - wet weather, fading light, on a very demanding corner, over a blind brow.

There is less risk of that happening at one of the newer, flatter tracks, with vast run-off areas. But unquestionably the drivers would say there is less pleasure in driving there than at Suzuka.

That's not because they think for one minute that the possibility of death should be part of the challenge.

It's because the consequences of a mistake are much greater. Instead of running wide and rejoining the track, they could damage the car, even have a crash. And even if you are 'uninjured' in a crash, believe me, they all hurt.

It is the difference between putting 50p on a roulette wheel and £50,000.

The bigger the competition, the higher the stakes, the greater the satisfaction.

Therein lies the fundamental conflict - and appeal - at the heart of F1.

David Coulthard was talking to BBC Sport's Andrew Benson

- Published19 July 2015

- Published18 July 2015

- Published18 July 2015

- Published18 July 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published2 November 2018