Motorsport must find a way to protect drivers - Allan McNish

- Published

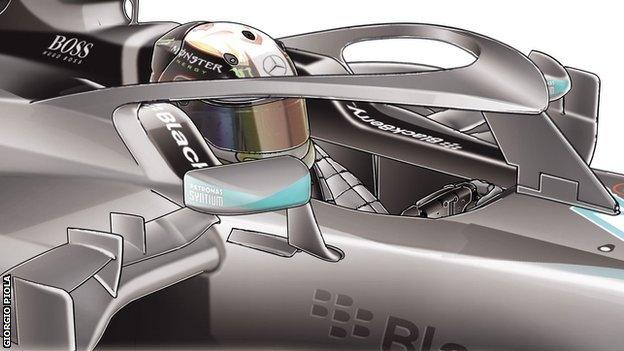

An artist's impression shows one of the latest designs for driver protection in the cockpit

The debate about cockpit head protection in Formula 1 and other single-seater racing categories has been reignited by the death of British driver Justin Wilson in an IndyCar accident last week.

In fact, Wilson's death has merely underlined what was already obvious - this is a problem that needs solving as soon as possible.

The fatal incident involving Wilson, who was 37, was the latest in a series of accidents that have highlighted that the drivers' heads are now the single biggest concern in crashes of this type of racing car.

A worrying trend

The issue of safety for drivers in the cockpit area was brought back into focus following the death of former F1 driver Justin Wilson

A month before Wilson's death, F1 driver Jules Bianchi finally succumbed to head injuries that had left him in a coma since a crash in the Japanese Grand Prix last October.

In the last six years, there have been a series of major accidents that have either killed or seriously injured drivers:

Maria De Villota sustained head injuries that led to her death in an accident during an F1 test

Dan Wheldon died after his head hit a fence post in an Indycar accident

Dario Franchitti had to retire because of suffering too many head injuries in his IndyCar career

Felipe Massa, external suffered a fractured skull during qualifying for the Hungarian Grand Prix

Henry Surtees,, external the son of 1964 F1 world champion John, was killed by a loose wheel in a Formula Two race

Beyond that, there have been a series of close calls.

In F1 this year, two-time world champion Fernando Alonso has twice had accidents which highlighted the vulnerability of the head as a major concern in F1.

The Spaniard suffered concussion in a crash at Barcelona in pre-season testing, and was lucky not to be injured when his McLaren ended up on top of Kimi Raikkonen's Ferrari after the Finn lost control on the first lap of the Austrian Grand Prix.

Even at the most recent F1 meeting in Belgium just over a week ago two accidents in support races highlighted this concern.

In the GP2 race, Daniel de Jong, external hit his helmet on the tyre barrier in an accident in which he also suffered a broken back; and in the GP3 event a loose wheel hit the front of the car of Matt Parry, just a couple of feet from his helmet, an incident very similar to the one that killed Surtees.

Then there was the series of crashes in practice for this year's Indy 500 in which cars overturned at more than 200mph.

Each one of those accidents can be - and has been - described as "freak", in the sense that the specific circumstances were unusual and unlikely to be repeated.

But it is abundantly clear that there is a trend about which something needs to be done.

This is a large part of the reason why the F1 drivers were so sensitive to the two high-speed tyre failures suffered by Nico Rosberg and Sebastian Vettel at the Belgian Grand Prix.

Rosberg and Vettel - and their colleagues - were very aware that had those incidents happened a couple of hundred metres earlier or later, they would have led to very severe crashes at close to 200mph.

How motorsport injuries have changed

The force of the impact at Jerez in 1990 was so violent it cracked Donnelly's helmet causing bruising to his brain

When I started racing in the 1980s, the biggest concern tended to be severe leg injuries, or big crashes that might not have killed you, but gave you major problems for the rest of your life.

There are a lot of ex-F1 drivers from the 1980s walking around with pronounced limps at the moment because of the vulnerability of drivers' legs in an F1 car in those years.

And Martin Donnelly is an example of the full-body crash. His Lotus pretty much exploded around him when he crashed at Jerez in 1990, and he was very badly smashed up in the impact.

But as safety has improved in a number of areas - the understanding of carbon fibre, how to attach suspension more effectively, impact tests and so on - the majority of serious accidents now involve head or spinal injuries.

Head injuries were always the ones I worried about most in my career, because the recovery from them is so unpredictable.

Evolution is inescapable

It can be instructive in situations such as this to look back at how the sport has evolved over time.

Take helmets as an example. Back in the 1930s, the spectacular Mercedes and Auto Union 'silver arrows' that dominated grand prix racing could top 210mph on the old Nurburgring - and the drivers wore helmets made of leather.

I've driven one of those cars, and I can tell you that is a terrifying thing to think about, but back then it was accepted as normal.

They did not have seat belts either - if you had an accident, the best outcome for the driver was to be thrown away from the vehicle.

Things have thankfully evolved massively since that time and they continue to do so.

The development of helmets

The contrast in Formula 1 helmets is evident, from Argentine driver Juan Manuel Fangio in 1956 to the present day ones worn by Lewis Hamilton and others

Examples of how F1 has continued to learn from experiences can be seen in the accident that killed Ayrton Senna at Imola in 1994, and Massa's crash in Hungary in 2009.

Senna was killed by a suspension arm piercing his helmet. Since then, cockpit sides have been raised, wheel tethers have been introduced to stop wheels coming off cars in accidents, and the survival cell of an F1 car has been made much stronger, particularly in its ability to absorb the energy of an impact, through the use of regulatory crash tests.

Massa was hit on the head by a suspension part from another car, weighing just 2kg, and that has led to a major improvement in helmet safety.

Visors are now effectively bullet proof - because a stone flicked up by a wheel of another car effectively behaves very much liked a bullet from a gun - and helmets are now made of carbon-fibre, and are much more effective at dissipating the energy of impacts than they were pre-Massa.

Additionally, attached to the top of the visor is a strip of a composite material called Zylon, further improving protection to the weakest area of a helmet, around the open aperture.

What is the solution?

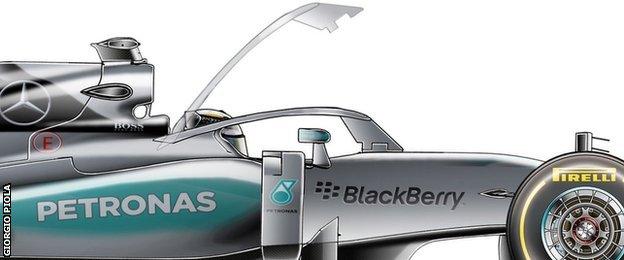

An artist's impression shows one of the latest designs for driver protection in the cockpit

The next step in driver head protection remains unclear, but a number of ideas have been floated to reduce the vulnerability of drivers' heads.

Among them are canopies and other forms of structure that protect the head from an impact from in front or above.

Governing body the FIA is conducting more testing on a variety of solutions later in September. One will be the 'halo' you can see in this article. That's an idea that came from Mercedes, although the team have come up with further ideas since.

Time to dismiss the objections

There have been objections to this process, many of which are on the basis that such devices are somehow contrary to the essential nature of the so-called DNA of single-seater racing.

But there are convincing reasons to dismiss those objections.

Firstly, in today's society, motorsport cannot afford to be seen not to be making itself as safe as it can be.

Secondly, it is hard to sustain an argument about the "essential nature" of F1 when it has changed so much over the years.

Thirdly, are we really so sure that open cockpits are the DNA of F1?

While these types of racing cars have tended to be designed with open cockpits - and that design is now dictated by the specifics of the regulations - they are not intrinsic to the name of the sport. Depending on which side of the Atlantic you are on, they are called either single-seaters or open-wheelers, not open cockpit.

Equally, part of F1's image is about pushing boundaries, and being at the forefront of new technologies. Safety is just as much a part of that as anything else.

Another argument made against head protection is that it could obstruct a driver trying to get out of a car quickly if it overturns.

But that point is anachronistic. I cannot think of one incident in the last 10 years in which a driver has had to scramble quickly out of an upturned car.

That's because the advance in fuel-cell and fuel-line technology means fire is not the risk it used to be.

Not only that, but if a driver has a large accident that requires a safety team to get him out of the car, then he is extracted in his seat, and that takes minutes, not seconds.

The 'halo' canopy is one of the ideas put forward by Mercedes to increase driver's safety

The arguments against increased canopies and the like remind me a little of the introduction of the Hans (Head And Neck Safety) device about a decade ago.

The Hans is a yoke that goes around the driver's shoulders and is attached to the helmet. It drastically reduces the risk of lower skull fractures because it prevents extreme movements of the head and neck.

When that was first introduced, lots of drivers complained that it was uncomfortable, but they were forced to use it.

Over the years its effectiveness has been proven beyond doubt. And nowadays, if you get into a car without it, you feel naked.

That is not to say there are not potential problems. And one real concern is that some of the structures proposed could restrict vision and therefore the potential for extra risk.

Final thoughts

Exploding tyres in F1 have raised safety concerns for drivers whose heads are exposed in the cockpit of their cars

I find it useful to separate the concepts of risk and danger.

Racing is dangerous. That is an immutable fact.

Kinetic energy is a function of the square of speed. Energy is what does the damage in an accident and what needs to be dissipated to increase safety. So, by definition, hurtling along at high speed in a projectile can never be safe.

We want to reduce danger but removing it altogether is impossible. However, the sport can reduce the unnecessary risks and doing so is only logical.

As drivers, we accept that a large element of racing is gladiatorial and that there is an inherent risk in what we do.

But, in general, we do not accept that risks should be unlimited, that nothing should be done to reduce them, or that there is any such thing as "safe enough".

When it comes to issues of safety such as this, it is vital that whatever solution is adopted, it is the one with the most positives and the least negatives.

To establish which solution meets those criteria will take some time.

It has to be the right solution at the right time, not the wrong solution because it is quick.

But the biggest negative would be to do nothing at all.

Allan McNish was speaking to BBC Sport's chief F1 writer Andrew Benson

- Published26 August 2015

- Published26 August 2015

- Published18 December 2015