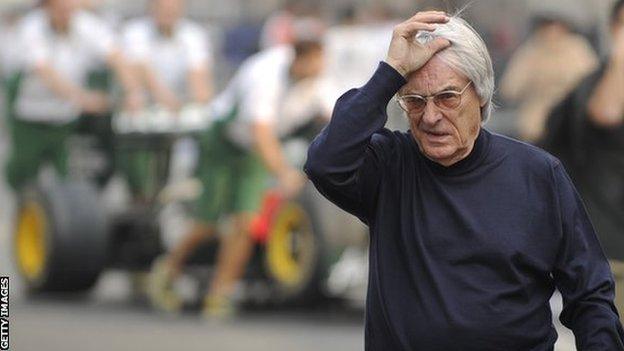

Bernie Ecclestone battling to keep a grip on Formula 1

- Published

The future of Formula 1 is uncertain unless changes are made, according to Bernie Ecclestone

Is Formula 1 in crisis? Well, it is according to the sport's commercial boss Bernie Ecclestone.

Television audiences are down, Ecclestone says, teams are struggling to survive. Something needs to be done.

That's what the 85-year-old told a meeting of the FIA World Council, F1's main legislative body, last week.

The upshot of that, and the conversation that followed within the governing body's headquarters in Paris, was Ecclestone and FIA president Jean Todt were granted unprecedented powers "to make recommendations and decisions regarding a number of pressing issues in F1".

What does that mean? In a nutshell, it is the latest salvo in an increasingly tense fight for power and influence in F1 that could change the future direction of the sport.

'For Ecclestone, this is a nightmare'

Ecclestone and FIA president Jean Todt (right) may have joined forces but how long can their alliance last?

The plan discussed by Ecclestone and Todt with the FIA World Council was to cut the F1 teams out of the decision-making process, to which they have had a legal right for 35 years.

Why? Because Ecclestone's power is arguably at an all-time low.

An example of this was seen just a couple of weeks ago, when there was a remarkable development that received relatively little coverage.

Todt and Ecclestone had proposed a reduction in the prices of the engines supplied by the manufacturers to their customer teams - an issue that has caused controversy since the introduction of the controversial turbo hybrid engines in 2014.

Ferrari used its contractual right of veto to block this plan. So Todt and Ecclestone came up with another - an alternative engine, that could be supplied at a fraction of the cost of the turbo hybrids, and would run alongside them under a complicated equivalency formula.

But that plan, too, was blocked, this time by the F1 Commission, the stage of the legislative process before the World Council and on which sit representatives of all the teams, plus of circuits, sponsors and tyre supplier.

So a rule change desired by both the FIA president and the commercial rights holder was blocked thanks to the power of the car manufacturers in F1. It was a momentous, almost unprecedented, situation.

For Ecclestone, this is a nightmare. Power and control are his raison d'être. And he is determined to get them back. Hence the persuasion that led to the granting of dramatic new powers.

What's the battleground?

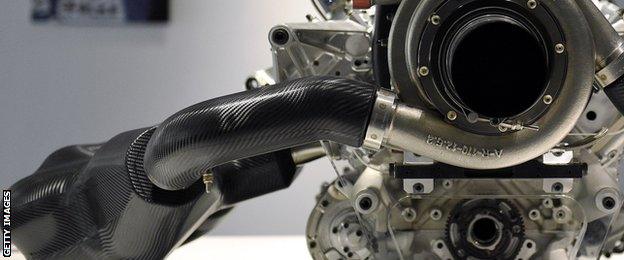

The debate over engine noise and cost was a focal point of the 2015 F1 season

The subject over which this battle will be fought is engines. While the manufacturers managed to stop the 'alternative engine' at the F1 Commission stage, they did agree to address several concerns.

These were: the supply of engines to customer teams; reducing engine cost; simplifying engines, and 'improving' the sound they make.

Cost, complexity and noise have been subjects for discussion since even before the turbo hybrids first raced last year.

The issue of supply arose following Red Bull's attempt to split with Renault.

Cynics have suggested Red Bull - whose boss Dietrich Mateschitz is a close ally of Ecclestone - might have invented the whole situation as a way to leverage the political situation in which F1 now finds itself. And that Ecclestone, working in cahoots with his old ally and former FIA president Max Mosley, planned where F1 is now months ago. But there is no proof of that.

The manufacturers have been given a date - 15 January - to report back with their proposals. And there is another date of importance - 31 January, by which time, the World Council says, Todt and Ecclestone will produce their own conclusions as to what they will do with their apparent new mandate.

The implicit threat is obvious - come up with solutions to what is deemed to be a problem with the engines, or have the 'alternative' engine forced upon you.

And the manufacturers won't want that - because they know the cheaper engine could be legislated to be as competitive as it is needed to be. And it only needs one team to run it - presumably Red Bull - and the power of the manufacturers is removed at a stroke.

What changes are coming?

Well aware of the threat, the engine manufacturers have been working on their proposals.

Inevitably, given the stated need to increase engine noise and reduce their cost and complexity, attention has focused on the part of the hybrid system that recovers energy from the turbo.

This is called the MGU-H, and it is central to the ethos of the current F1, which is about fuel efficiency.

The MGU-H is situated within the turbo system. It recovers energy from the exhaust gases, and reapplies it both to eliminate turbo lag and to boost the overall power and efficiency of the engine.

The reason the MGU-H was included within the current engines is that it is a cutting-edge piece of technology directly related to development in road cars.

According to Mercedes engine boss Andy Cowell, it is the one area where development in F1 is ahead of technology in road cars, with manufacturers hoping to use the knowledge gained in the production of road cars in the future.

The problem with the MGU-H and related systems is it is expensive and complicated - it is mastery of this area, for example, that is central to Mercedes' dominance of F1 and also to the struggles Honda has had this year.

Red Bull have been pushing for two years for it to be dropped - arguing its cost and complexity is threatening the sport by making success too dependent on engines.

This argument is clearly gaining traction. Mercedes, Ferrari and Renault have proposed getting rid of MGU-H, but Honda is implacably opposed. It says the MGU-H is a central part of its F1 strategy with a Honda representative saying his colleagues would be "idiots" to get rid of it.

Nevertheless, that does seem to be the direction things are heading.

The likely scenario is F1 will continue with the same fundamental architecture as the current engine - a 1.5-litre V6 turbo, but with only a kinetic energy recovery system on the rear axle, and the MGU-H replaced by something called an e-booster; similar to the MGU-H but without the energy recovery aspects.

Todt wants the changes for 2017, but the manufacturers say that is not possible, and 2018 is realistic.

And once the calendar clicks over into 2016, no changes can be made for 2017 without the teams' unanimous consent. Which, at least in theory, prevents Todt and Ecclestone imposing anything.

What if there's no agreement?

But what happens if either there is no agreement from the engine manufacturers, or Todt and Ecclestone decide they don't like what they come up with?

There are two issues here. One is how long the marriage of convenience between Todt and Ecclestone, who were enemies not long ago, will last. The other is whether they have the powers they think they have, following the World Council decision.

Todt's agenda seems clear - he backs hybrid engines but wants the price to come down and for all teams to get them when they need them.

Ecclestone's agenda is equally clear - he doesn't really care what the engines are, as long as he gets back as much power and control as possible.

So if Todt gets his way on engines but Ecclestone does not win back the authority he craves, does the alliance last?

Do Todt and Ecclestone now have absolute power?

Sergio Marchionne (left) has said of engine changes: "If somebody would know the costs involved in the development, the prices we talk about don't even cover spark plugs."

Todt and Ecclestone's "mandate" from the World Council is based on the claim the only contract in which the detail and role of the strategy group of leading teams and F1 Commission are enshrined is the one between the FIA and commercial rights holders CVC Capital Partners, for whom Ecclestone works.

But, sources say, at least some of the teams' contracts mention those two bodies as well, even if they are not as explicit.

Can these contracts be ignored? Given the power and influence of the people who hold them - massive global manufacturers such as Daimler-Benz, Fiat, Renault-Nissan and Honda - that has to be considered unlikely.

There is also Ferrari's contractual right of veto over any rule changes that are contrary to its interests.

New Ferrari president Sergio Marchionne, a hard-nosed businessman, has already used the veto once, and would surely be prepared to do so again.

Equally, the argument for imposing rule changes would be based on the sustainability of the sport. But that can work against Ecclestone/CVC as easily as it can for them.

After all, falling TV figures or not, more than enough money comes into F1 - about $1.5bn (£1bn) a year - to make the entire sport sustainable. The problem is a) that the way that money is distributed is heavily skewed in favour of the leading teams; and b) 37% of it stays with CVC.

If more of that money was invested back in the sport, rather than used to service CVC's debts and shareholders, the teams could have more than enough to survive, even at the current engine prices. And a more rounded view could be taken towards race fees, which one senior F1 insider describes as "scandalous".

For example, at the moment, the future of the US Grand Prix is under threat because of a cut in funding for the event from the state of Texas. The shortfall in question is about $6m (£4m). The potential loss of that race would, one senior insider said, "be disgraceful".

The World Council might not be making these arguments to Todt and, in particular, Ecclestone. But others might - and there is the shadow of a potential EU investigation into anti-competitive practices in F1 to worry about, too, following an official complaint by the Force India and Sauber teams.

This could play against Ecclestone - in terms of the prize-money split - but also for him - in that being forced to tear up the existing contracts and renegotiate them might lead to a redistribution of prize money in which CVC could keep more. The EU may also raise questions about one team having power of veto over any rule change.

The next few months will be interesting indeed.

- Published25 December 2015

- Published9 December 2015

- Published7 December 2015

- Published7 December 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published2 November 2018

- Published26 February 2019