Australian Grand Prix: Formula 1 returns, but will changes make it be better?

- Published

- comments

The crisis is over. At least that is how it seems on the eve of arguably the most important Formula 1 season for a long time.

After three years in which the sport agonised over declining television audiences, a lack of competition on the track, uninspiring cars and an apparently large number of disgruntled fans, F1 seems to be back on track.

The cars that will race for the first time in Melbourne on Sunday are an attempt to put visceral thrills back in a sport many felt had lost its way.

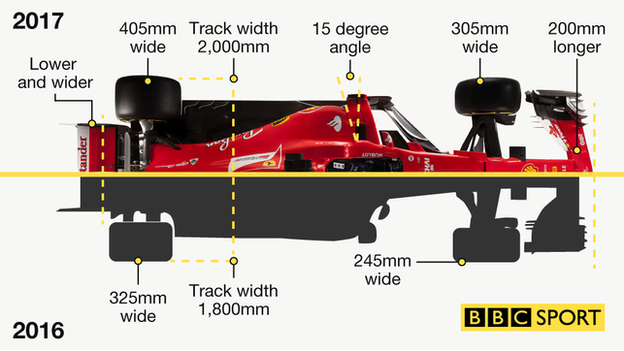

The rule-makers had a simple target - cars that were up to five seconds a lap faster, that tested the drivers to their physical and technical limits, which they could drive flat out most of the time and which looked, well, sexy again. At the same time, overtaking should not be any harder than it already was.

The message from two weeks of testing in Spain was the goals have been achieved. Except maybe the last one.

And - whisper it for now - more than one team might even be able to win.

"The car is amazing in terms of the speed we carry through the corners," three-time world champion Lewis Hamilton said of his Mercedes. "It is definitely the fastest I have ever been in F1."

"They look cool," says Red Bull driver Daniel Ricciardo. "They look pretty mean. And low and fat. Kind of old-school. It is going to be fun."

Red Bull: possibly not the fastest, yet, but it does have a secret hole in the bodywork everyone seems to think will make it very good

Why have the cars been changed?

"It all started because the drivers were not happy with the grip levels," says Alexander Wurz, chairman of the Grand Prix Drivers' Association.

The route to F1 2017 began two years ago, when drivers finally began to give organised voice to a dissatisfaction with the cars that had been growing since Pirelli became the sport's tyre supplier in 2011.

Tyres that could not be pushed hard lest they irretrievably lost grip meant drivers had to lap seconds off the pace in races to eke out predetermined ideal stint lengths.

Initially, the sport's leading bosses - on the strategy group - thought drivers were saying the cars were not difficult to drive. Eventually, they realised the message was the cars were "not physically demanding and cool", as Wurz puts it, "and there was a need for something mega".

"You can see from the tests that the new rules are back to a ratio of power and grip and lap time where a race driver is not always easily at the limit of the car," says Wurz, who is also an adviser to the Williams team. "He also has his own limits, which are physical, concentration, respect. That's a good success for the whole industry."

Or as Ferrari's four-time world champion Sebastian Vettel puts it: "From a driver's point of view, it's better pretty much everywhere. Braking is better, cornering is better, you've got much more grip.

"Then in low speed, where arguably downforce effect is less, you have wider tyres so the grip from them, it works pretty much like an aspirin, it fixes everything. It's difficult to compare. It's a different animal, a different beast."

Wurz adds: "The new rules are such a massive step forward and that's why they will be successful despite having potential issues with overtaking which we can address later."

What? Overtaking issues? Surely not...

The cars may well be spectacular to watch and fantastic to drive for the first time in almost a decade but will the racing be good?

Hamilton is one of the many drivers who have said they believe the huge increase in aerodynamic downforce will inevitably make passing more difficult.

"Following is not good," he says. "It is worse to follow another car. I don't know how that will work out in a race."

The issue here is downforce, and specifically how that downforce is created.

Palmer's guide to the new F1 cars

An F1 car needs clean airflow to work at its best. Put it in turbulent air - such as that created by another car - and the finely tuned airflow that starts at the front wing and cascades backwards over all those pieces of bodywork along the sides of the cars is disturbed. And the downforce is dramatically cut.

"Now the turbulence is easily twice as powerful coming out the back of a car," Hamilton says. "It magnifies the issue we had before. Let's hope the racing is fantastic, but don't hold your breath."

There is another aspect to the potential effect on the show, too.

The new tyres Pirelli have produced are vastly improved in terms of allowing drivers to push hard for long periods. But this has been achieved by, among other things, making them harder. That means they last longer, which almost certainly means fewer pit stops, at least in the first few races for which the tyre compounds have already been chosen.

The season-opening race in Australia, for example, is already expected by engineers to feature only a single pit stop for each car. Most races will almost certainly have one fewer pit stop than last year.

The thorny issue of authenticity

Overtaking and, to a lesser extent, the number of pit stops, are issues about which many fans get very worked up. And yet so is a device that was introduced seven years ago to make overtaking less difficult - the drag reduction system (DRS). This is not the paradox it at first seems.

The DRS is a flap on the rear wing which the driver can open at a designated point if he is within a second of another car. It increases top speed by well over 10km/h and has led to what has become a rather denigrated feature of F1 - the so-called 'DRS pass'.

This is when a driver has such a speed advantage as a result of DRS that he simply drives past his helpless rival on the straight. That has rather diminished what is supposed to be one of the highest levels of skill a racing driver possesses - the ability to overtake a rival.

Hamilton describes DRS as "a bit like a Band-Aid for the wrong rule changes in terms of the way the cars are designed and built".

F1 needs a fresh start - Carey

Wurz says: "Authentic is the biggest word here. In the mid-2000s, there was less overtaking than at any point in F1 history but currently the biggest hype is about that period of time. It's because the product was fit for how people felt.

"Since then, it has been diminished to be an artificial show to achieve overtaking. They maybe achieved it, but it wasn't authentic or heroic. It was too much, too easy and the consumer understands that because no-one will ever scream about an amazing DRS overtaking manoeuvre.

"If there is just one amazing overtake in a race, that delivers much more energy and emotion to the consumer than five DRS fly-bys."

What to do about it

F1 is a restless beast. It's part of what makes it a success; the constant drive to be better, the refusal to accept that something is good enough.

It is unsurprising, then, that before these new wider, faster cars have even raced, the thoughts of the sport's power brokers are already turning to what's next.

F1 is under new ownership this year and Ross Brawn, the former Mercedes team boss now in charge of shaping the sport's future direction, has said he wants to get rid of DRS.

But that is one tiny part of negotiations, that are just starting, about what F1's future might look like. Overtaking will be part of those conversations. For Wurz, the issue is less overtaking per se, more whether the design of the cars allows for close racing.

"Some say overtaking is so important for fans to be attached to F1," he says. "From the beginning, I have said - and I believe - that is not the answer. It is maybe not even true.

Lewis Hamilton says Formula 1 has 'a lot of catching up to do'

"Generally, I believe the most important thing is competition - and not just between two team-mates but between a few teams - and that the races are close. So I think it is fundamental that the aerodynamic philosophy should change so it is not so sensitive driving behind each other. And that can be achieved."

Not only is Wurz the GPDA chairman and a former F1 driver, he is also a two-time winner of the Le Mans 24 Hours and spent the last few years of his career in the World Endurance Championship.

The cars he raced - the so-called Le Mans Prototypes from Porsche, Toyota and, until last year, Audi - had even more downforce than F1 cars, but can be raced close together without problem.

"In a Le Mans car," Wurz says, "following someone in a 150mph corner, never at any point do you have to think you have to keep your distance because otherwise you are going to slide wide without control.

"You almost touch his bumper and your car will generate the same grip as when you drive by yourself. So all your focus can be solely on the guy in front, to find a little gap or a little mistake and you are close enough to strike.

"In an F1 car, when you go behind someone, you are always thinking: 'OK, I am that close, so I must enter the corner a little bit slower because otherwise I am going to slide too wide in the mid-corner and apex and I am going to lose too much time or even make a mistake.'

"Unless you have much fresher tyres or he makes a mistake, you cannot think: 'OK, I am that close now, I will strike.' And by nature in F1 not too many people make mistakes."

The explanation for this is to do with how the car generates its downforce.

An F1 car's aerodynamics are focused on the front wing. Even the airflow through the diffuser - the back of the car's floor, which is so crucial to overall performance - fundamentally comes in from the sides of the car having been accelerated around it in a process that starts at the front wing.

In an LMP1 car, the downforce is generated almost entirely under the floor - just as was the case with F1 cars when the era of aerodynamics properly started back in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Take a look at a car from, say 1982, and you'll either see no front wing, or a very small one used only for fine-tuning. Like WEC cars, IndyCars in America use this philosophy now, so cars can race closely at 220mph and more on oval tracks.

Changing this philosophy in F1 would not be easy - there would inevitably be resistance from the leading teams who best exploit the current rules, even though, as Wurz puts it, "if you're the best before, you'll be the best after".

Right now, this discussion, as much as it has started, is revolving in public only around the potential difficulty of overtaking. It is yet to move on to what to do about it.

But if Hamilton's fears are borne out, it is not hard to see how it could.

- Published16 March 2017

- Published11 March 2017

- Published10 March 2017

- Published2 March 2017

- Published21 February 2017

- Published16 February 2017