Formula 1: A Silverstone bonanza and desert double for the 2020 season?

- Published

More than 140,000 fans came to Silverstone to watch the British Grand Prix last year

Formula 1 has laid out its ambition to start up the season in early July, by which time it hopes the coronavirus crisis will be sufficiently under control for the sport to go racing, albeit under significant restrictions.

F1 boss Chase Carey hopes to complete a season of at least 16 races in a year that has been laid waste by the coronavirus crisis, but there are complications around what national governments will allow F1 to do, how it might do it, and the restrictions it would have to work under.

So how would this work? BBC Sport has been talking to insiders in an attempt to put a shape to the season F1 hopes will come.

How would the season start off?

Plans are inevitably not firm, as the medical situation in countries around the world is changing all the time.

But under the current trajectory, with many European countries looking to be going down the backside of the coronavirus infection curve, F1 has sketched out a plan for a few races in Europe to start the season off in the summer and then a sweep east, a dip into the Americas before rounding off the season in the Middle East in December.

Easy to say; not quite so easy to do.

The plan for Europe - where Monaco has already announced it will not hold a race this year - is relatively straightforward, at least to start with.

Carey has already announced its intention to start the season in Austria on 3-5 July. What has not been announced, but is in the works, is a plan for a second race in Austria on 12 July, followed by two at Silverstone on 19 and 26 July.

These four events would be behind closed doors - so no paying spectators and no corporate guests - and F1 is discussing with the authorities in each country how it might safely move in enough people to stage a race.

Will this require F1 personnel to be tested for coronavirus before they travel and to socially distance from the local population while there? Quite possibly.

After that, the next races could be in Spain, Hungary and France, or a selection thereof, depending on where each country is in its virus recovery phase.

France's nuanced announcement on Monday that its race was off does not preclude the fact that talks are ongoing about holding a race at the Paul Ricard circuit later in the summer - it would just not be the official French Grand Prix.

Then there are question marks over the two most historic races in the calendar, the Belgian and Italian Grands Prix.

Spa is looking shaky. Belgium has extended its ban on mass gatherings to the end of August, which means its race would have to be in September, and that gives a very small weather window to hold it in the Ardennes mountains - and knock-on logistical problems for the rest of the season.

The revived Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort, due to be held this year for the first time since 1985 to ride the wave of Max Verstappen-mania, also looks in serious doubt, after that country also extended mass-gathering restrictions until the autumn.

As far as Italy goes, it was the epicentre of coronavirus in Europe and that has left its scars, so F1 is particularly aware of the potential sensitivities of holding an Italian Grand Prix.

On the other hand, there is political pressure to hold the race, from both Ferrari and TV company Sky Italia, sources say. And because of the importance of both F1 and Ferrari in national life in Italy, there is an argument that a grand prix could give the country a much-needed boost.

Could the inaugural Vietnamese GP make a comeback after being postponed from its original April date?

What about after Europe?

Two other races pretty much have to be held in September if they are to happen - Canada and Singapore, for different reasons.

The issue in Montreal is that the winter sets in early and is harsh. So anything beyond the first weekend in October, when the race was held when it first came on to the calendar in 1978, would be too big a risk weather-wise.

Singapore, meanwhile, because it's a street race that causes major disruption to the city state, has to be held on its scheduled date of 20 September, or not at all.

That means that in all likelihood only one of those two races can be held before F1 heads off around the world region by region.

First, the Russian and Azerbaijan Grands Prix in Sochi and Baku, in late September/early October. Then, to Asia, and ideally all three of Japan, Vietnam and China.

After that, it would be on to North America and the US and Mexican races in Austin, Texas, and Mexico City, followed by Brazil. And then the Middle East for the final two races in Bahrain and Abu Dhabi, ideally in December.

Vietnam could move to before Bahrain to ease congestion a little.

It should be emphasised that this is merely a reflection of current thinking, and much could change in the intervening months.

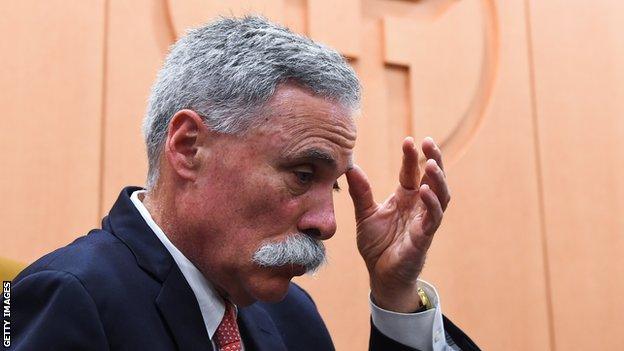

Thinking, thinking, thinking: F1 CEO Carey is dealing with quite a scheduling headache

Sounds ambitious - how practical is this?

Under normal conditions, the logistics of moving the teams and personnel around the world would be do-able, although the schedule will be extremely crammed and brutal for those involved.

The real difficulties surround what each country in question will expect from F1 in terms of controlling the virus, even assuming they feel a race could be held. Talks with all the government bodies involved will be required.

F1 is exploring all the ways in which it can reassure countries that it will not be a drain on their resources or contribute to spreading the coronavirus, as well as be certain its own personnel remain safe and healthy.

This could mean an intra-sport virus testing programme, the use of charter flights instead of scheduled, and restrictions on the number of people working at the race - including being selective about which media are able to attend, once F1 feels it becomes possible to let the media in at all, which may well not be the case at the start of the season.

Teams are looking at how far they can strip back their operations so that only people necessary to operate the cars go to the races. Keeping the media out and running the events simply as a pure television sporting spectacle, at least at the start of the season, is one key way of doing that because it removes the need for marketing and public relations to attend.

As for getting driver and team principal reaction out to the media and public, these could be filmed by F1's own staff for television, while teams could hold online news conferences.

Moving all the thousands of tonnes of freight around the world should be do-able. The difficult thing could be the movement of people

What about the money side?

How will all this work in the context of F1's business model?

Fees paid by race promoters and television broadcasters account for 68% of F1's income - 38% from TV rights; 30% from race-hosting fees.

The teams are paid 63% of F1's income and that collective pot of about $1bn is a huge part of their overall revenue. No races would mean virtually no money. So it's pretty obvious why it is so important for the sport to get back to racing as soon as is practicably possible.

But that raises questions about some of the races.

Take Silverstone, for example. It has spent years saying it could barely afford the British Grand Prix and, even after negotiating a new contract last year, it needs big crowds to turn even a small profit on hosting the race.

So if Silverstone can barely afford to host one grand prix with 140,000 paying spectators, how can it suddenly host two a week apart with none?

The answer is that F1 will look to effectively rent the circuit from the British Racing Drivers' Club, offsetting the losses the track will incur from not having any ticket sales.

This is an example of how F1 owner Liberty Media will have to dip into its own pocket to some degree to ensure the survival of the sport through this year, although there are only so many times it can do this without causing more problems than it solves.

A complex series of internal transactions within the Liberty Media Group last week gave F1 significantly more available cash to ride out these difficulties.

At the other end of the scale from Silverstone are races that are funded largely or entirely by the relevant government of that country or region as a global promotional tool.

In these cases, ticket sales offset the total cost to varying degrees, depending on the size of the crowd. But they are nowhere near as important to the overall business plan as they are for Silverstone or the US Grand Prix, for example.

For the likes of Abu Dhabi, Azerbaijan, Bahrain and Russia, as long as the grand prix happens, the promoters will almost certainly be happy to pay, as the overarching purpose of the race will still be satisfied, whether there are spectators or not.

TV rights money plays a big part in this picture, too.

Contracts are said to dictate fees must be paid in full as long as there are at least 16 races, with a sliding scale down as the number of races dips below that.

That explains F1's eagerness to pack the start of the season with double-race events, so it is easier to get to that magic number as the season progresses.