Saudi Arabian Grand Prix: 'Focus turns to Sunday's race, but big questions remain'

- Published

The Saudi Arabian Grand Prix is live on BBC Radio 5 Live and the BBC Sport website

The bosses of Formula 1 and the local authorities managed to talk the drivers into racing at this weekend's Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, but there is a lot more work to do to convince some people in the sport that the race should be on the calendar at all.

It took four hours of meetings on Friday evening for the drivers to be persuaded they should race this weekend, after a missile attack on an oil facility nine miles from the circuit lit up the night sky on the Jeddah corniche and initially convinced many of the sport's stars that the grand prix should be called off.

As the drivers sat in a glass-walled room in the paddock, and Friday turned into Saturday, various senior figures came and went from the meeting - the team principals, F1 chairman Stefano Domenicali, FIA president Mohammed Ben Sulayem, ministers in the Saudi government.

And eventually, the drivers agreed to go ahead.

But 24 hours later, the top three men after qualifying did not exactly sound as if they had been turned into ambassadors for the race.

Should Saudi Arabia have a future in F1, Red Bull's surprise pole winner Sergio Perez and the Ferrari drivers Charles Leclerc and Carlos Sainz were asked?

"There are some considerations we all have to make as a group and see what's best for the sport going forwards," Perez said.

"It is definitely a discussion we should have after this race once everything calms down," Leclerc added.

'A tricky moment, to say the least'

Committing to a race in Saudi Arabia was always going to be controversial, given the country's human rights record. And F1 has sought to get in front of the accusation that it was complicit in allowing the regime to "sports-wash" its global reputation by saying it had secured guarantees from the government in its contract and that it hoped to be a driver for change.

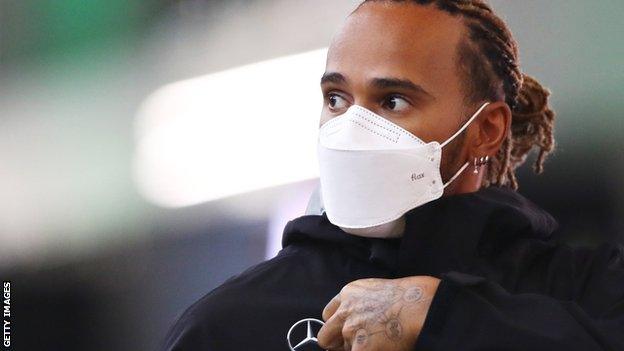

But Lewis Hamilton put the issue front and centre before last year's inaugural race when he admitted he wouldn't say he was comfortable being there, and did so again on Thursday when he said he had not changed his mind, and questioned why progress was not faster.

Other drivers are known to have similar concerns, but chose to keep them in the background, or - lacking Hamilton's profile and impact - were simply not asked how they felt.

But with an oil depot in flames, and plumes of black smoke visible from the track, the issue could not be avoided.

The strike was claimed by Yemeni Houthis, with whom Saudi Arabia has been fighting a war for a number of years. And the parallels with F1's decision to cancel the contract of the Russian Grand Prix after the invasion of Ukraine were clear.

Even F1 boss Stefano Domenicali admitted it. "When I saw that smoke just over there, it reminds [you] of a lot of things we see on TV," he said. "It is pretty clear that was the connection."

No-one has explicitly admitted it on the record, but it seems that shortly after the end of second practice on Friday, the drivers were set in their decision to pull out.

Mercedes team principal Toto Wolff said: "The drivers were pretty united in their initial discussions but, when they heard from us and the officials, we were able to convince them that the race was the best thing to do."

In the day following the meeting, the big question was what the drivers had been told that made them change their minds.

All Saturday, bosses talked of "reassurances", that their safety had been guaranteed by the Saudi government.

"Rationality over everything," Domenicali said. "It has been an intense day, sharing with openness, which is the right thing to do for the modern F1.

"There has been a lot of debate, but security is at the maximum level of attention for all of us. And when you talk to the right authorities, the minster of defence and of internal security, when we received assurances everything was under control, we need to rely on that. We inform the teams and drivers and we need to move on."

'We were considering all scenarios'

Domenicali's words were echoed by team bosses up and down the pit lane, all preaching from the same party line. That the attacks were relatively commonplace in Saudi Arabia - there was one in Jeddah last week while F1 was racing in Bahrain - and always targeted against infrastructure and not civilians or events.

But that argument raised questions. How is it possible to guarantee security against a missile strike? If a missile can hit an oil depot, surely another could hit a race track close by?

Sainz conceded the drivers had been asking themselves the same things.

"We were considering all possible scenarios," he said. "But in the end we all came together. It is 20 of us, with 20 opinions and 20 considerations, 20 different people talking, so it is always going to take a long time.

"In the end, we concluded probably the best thing is to listen to the authorities here and trust them and there is not much more we can do."

Leclerc said: "It was more a matter of coming together as drivers to share our opinions and feelings at that moment because it was a tricky moment to say the least."

"We were concerned about our safety but also the safety of mechanics, engineers, everyone," Perez said. "This is a sport and we are all in it together."

None of the drivers were prepared to share details of the meeting's content. It went through several phases - with and without team bosses, and with and without F1 bosses and government officials and so on.

Wolff said that the government "made it clear to us that the worst-case scenario was not cancelling the race but was that there would be a situation where we were unsafe and at risk".

The meeting did not just address whether it was safe to race, and the right thing to do, but also the potential consequences of any decision not to, many of which were not known, but could be imagined.

F1 and the FIA insist that at no stage was there any suggestion from the race organisers or the government that there could be any negative consequences for F1 personnel from a decision to cancel the race - delays to freight or staff leaving the country, for example.

But that is not the same as that possibility never entering discussions between some of the parties at some stage, which BBC Sport has been told it did.

Hamilton has been uncomfortable inside and outside of the car

'These things happen here'

Saudi Arabia pays one of the largest race fees on the calendar - a reputed $70m (£53m) a year - and has one of the longest contracts. The country also pays for advertising at tracks for its national oil company, which is one of the sport's biggest sponsorship partners, and is working with F1 on the fully sustainable fuels the sport plans to introduce in 2026 as part of its plan to go carbon neutral by 2030.

But the link with Saudi Arabia was always going to carry risks. The reputational ones were already understood, and F1 always had an argument for that.

"Does Saudi Arabia and some of the other Middle Eastern countries share the same values, the same culture as we do in Europe?" Wolff said. "They don't.

"Are they where we want them to be? No. Can we put the spotlight into this place by racing here in F1 and making those things visible and making it a better place? I still think so.

"I would rather come here and make the spotlight shine on the region so it needs to be in a better place rather than say: 'I am not going there; I don't want to hear anything of it.'"

But a missile attack in full view of the race track on the actual race weekend is something else. That seems not have been factored in. And if it was, no-one told the drivers.

"I love going to Tel Aviv," Wolff said, "but if you are in Tel Aviv you are pretty used to situations where drones are being flown over. It goes both directions.

"There wasn't any attack into Saudi Arabia that caused any civilian casualties, as far as I have been told, for a long time, so that's why we just need to understand that it is culturally very different to how we see our western cultures.

"For us, is it acceptable if 10 miles away there is a drone rocket that is going into a petrol tank? Certainly not. But these things happen here."

By Saturday evening, people in F1 were trying to move the conversation on, but even then there was an admission that the issue was not going away.

"I think it's time to focus on the race," Sainz said. "There will be plenty to discuss in the future."

There were lots of other topics on Saturday evening after qualifying, prime among them fresh concerns about the safety of the track following the massive accident that has ruled Haas driver Mick Schumacher out of the race, and Hamilton's worst competitive performance for 13 years.

Hamilton gave succinct answers on that topic, which he blamed on a wrong set-up direction that gave him a lack of rear grip in a Mercedes car that is already struggling for competitiveness. He was also asked about the over-arching issue of the weekend.

"I am looking forward to getting out," he said.

Who were the greatest number 10s? Ranking the best players who wore the number

Becoming Batman: Robert Pattinson reveals all about taking on the iconic role