How F1 'gladiators' became 'a thing of the past'

What will safety in F1 be like in 10 years?

- Published

This season is turning out to be something of a classic in Formula 1.

Thrilling battles and a prospective title showdown have helped to dissolve early season memories of Red Bull's domination on track and controversy off it.

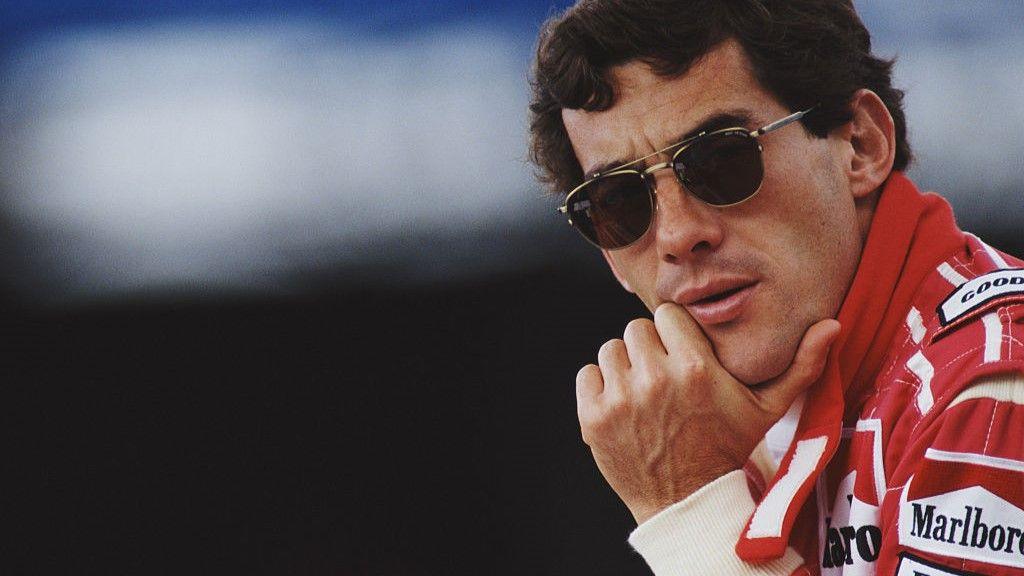

But it also marks 30 years since the death of the sport's most iconic figure - Ayrton Senna - in a crash which underpinned a professionalism and dedication to safety which still exists.

"Safety is one of the key principles or statues," says Nikolas Tombazis, director of single seaters for the sport's world governing body the FIA.

"Motorsport is always inherently dangerous; when cars are doing 300kph, you're never going to have complete safety, but we're doing a half-decent job - it's fairly safe, but we need to not be complacent and go further."

Ayrton Senna was killed in a crash at the San Marino Grand Prix 30 years ago

For a safer future, learn from the past

Tombazis was part of the Benetton team who were striding away from Senna at the beginning of the 1994 season - eventually winning the drivers' title with Michael Schumacher.

The 56-year-old Greek is warm and accommodating in the FIA's office at the Belgian Grand Prix - pausing for the constant drone of nearby racing - but focused.

"Maybe there was a romantic view of the past, where these guys competing were somehow gladiators or something," he says. "But that is a thing of the past. We don't assign to that. We must be as safe as possible.

"Every accident we examine in a lot of detail - what trajectory the car followed during the crash; what the reason was for it - there's usually a lot of factors.

"All of that goes in to learning how to improve the cars, the track, procedures… everything is analysed in excruciating detail by the safety department. There are always incremental changes."

Following Senna's death, several safety changes were made, including the introduction of accident data recorders in cars, higher cockpit sides and wheel tethers to aid head protection.

As part of new F1 regulations for 2026, the cars will be more resistant to front and side impacts.

"The nose of the car will be able to absorb a large amount of longitudinal energy," says Tombazis, "whilst having construction which will make sure if it hits the wall laterally, only part [of it] breaks off and another part remains for the subsequent impact."

Romain Grosjean's car was stuck inside the metal barrier after his crash in Bahrain

The halo - a higher power

Some of the new elements introduced for 2026 are developments prompted by a crash for Romain Grosjean at the 2020 Bahrain Grand Prix which even Hollywood couldn't have dreamt up.

On the first lap, Grosjean made contact with Daniil Kyvat's Alpha Tauri, which pitched his Haas into a barrier at high speed, exploding on impact as the car became wedged between the metal bars of the barriers which flank a large part of every Formula 1 circuit.

It was the type of crash the sport hadn't witnessed for decades, and one which frequently led to fatalities in the past.

Little has ever looked more gladiatorial than Grosjean rising from a huge ball of flames after squeezing between charred and twisted steel and striding across to a waiting ambulance, received by disbelieving marshals and medical staff.

"The engine split from the chassis," says Tombazis, "which is OK as such, but in splitting it ripped the chassis apart, and so it left the fuel tank exposed, thus fuel came out and it caused a fireball.

"We were very fortunate the driver was conscious and therefore could come out."

Tombazis then explained how the post-crash analysis process worked.

"Every car has an electronic box which logs a lot of signals," he says.

"It logs all the G-[force] loads of the car, therefore it's possible to calculate the trajectory of car as it was out of control and how quickly it decelerated and how hard it hit the barrier, and how it came to rest.

"This data gets analysed. In addition, the remains of the car, the chassis, gets analysed.

"Some of the subsequent analysis we did, we worked on how the engine would come off the chassis and applied further regulation to ensure that when the engine rips off, the failure points are bolts connecting the engine to the chassis and not the chassis itself.

"So now if things go as planned in similar circumstances, maybe the engine comes apart, but the chassis remains intact and the fuel tank also. So that's one outcome of that accident."

Grosjean, who now races for Lamborghini in the United States, credits the 'halo' head protection device for saving his life, after the structure around the cockpit helped to create enough space in the barrier for the Frenchman to escape.

"Without it, I wouldn't be able to speak with you today," said Grosjean after the crash.

There have been several clear instances where serious injury has been averted thanks to the halo and other innovations across the sport.

F1's current quickest man - McLaren's Lando Norris - agrees, highlighting the crash between Lewis Hamilton and Max Verstappen at the 2021 Italian Grand Prix.

"It can hold a number of double decker buses without breaking," he says. "Given the speed we do, it can deflect an enormous about of things.

“We saw with Lewis and Max, where Max's car ended on top of Lewis. If [the halo] was not there it would have been on Lewis' head - you never want to know what the consequences might have been if we didn’t have the halo."

Max Vertsappen's crash with Lewis Hamilton at the Italian GP in 2021 was one of the clearest incidents yet in which the halo prevented injury

How 'active safety' can be prevention

Norris believes safety in F1 is "improving all the time".

"You want an element of fear, it's what makes a racing driver - the barrier being one metre away at 200mph - but you never want something to go wrong," he says.

"When I sign up for going out and risking my life, I do that knowing what the consequences can be."

The innovations using carbon fibre construction techniques and advancements of other materials are impressive.

But according to Tombazis, future safety solutions could be more about prediction rather than projectiles. Including the use of artificial intelligence.

"We believe the best safety improvements in the next 10 years, I suspect, will be more in active safety: how to prevent accidents in the first place, rather than deal with what happens after an impact.

"How to prevent crashes meaning how to give better warnings to drivers about something happening further ahead.

"Not without proper study, but maybe to look at how we automatically warn other drivers, or slowing down cars approaching an accident scene - these sort of things we believe will be fundamental.

"A lot of developments in the road industry, a lot of safety improvements, are related to, let's say, cars talking to each other - so there's a lot of elements there.

"AI will be a key part about active safety - how we interpret the unfolding events during a race, or at the start of an accident or give a quick reaction, that will involve aspects related to AI."

In Bahrain four years ago, Grosjean said shortly after his crash: "I cannot die today - I want to see my kids."

With ongoing innovation, and a little luck, tomorrow's consequences could be a lot less dramatic.

Related topics

- Published30 September 2024

- Published31 July 2024

- Published29 August 2024