Olympic champion Anthony Joshua hoping to inspire a nation

- Published

As Anthony Joshua and his mum leaf through old photo albums in the kitchen of the family home, the joke is that the big kid's head used to be far too big for his body. But the big kid is now a man and the head is too big no longer, both literally and figuratively.

"I'm humble to be in the position I am," Joshua, who won super-heavyweight gold at the 2012 Olympics, tells BBC Sport. "I'm an ambassador for boxing: it gives me a chance to express myself and speak to thousands of kids because I've walked the path they're walking and come out on the positive side."

Joshua aims to be world champion

On Thursday Joshua announced his decision to leave the amateur ranks and turn pro. A heavyweight with amateur pedigree will have managers and promoters believing pretty much anything is possible, which is why the 23-year-old from north London via Watford was able to bide his time and study the options.

But the options appeared limited when, in March 2011, Joshua was arrested for possession of cannabis, external with intent to supply. He was sentenced to a 12-month community order and 100 hours' unpaid work. Worse, he was suspended from Great Britain's boxing squad. London Games? After a fashion.

"I wasn't getting funding so they were tough times," says Joshua. "I was just looking for an opportunity and you're not thinking about the consequences when you're younger. But I brought shame on myself and my family.

"It was really bad news for a lot of people who wanted to see me progress and I could see the pain it was putting my mum through. So I said to myself, 'This has got to stop. I'm a proud man and to be a Joshua is a privilege.'"

Perhaps scarier than being up in front of a judge was facing down the blazers of the Amateur Boxing Association of England. "It was up to them to allow me to continue," says Joshua. "I said my piece; I was honest. They knew I'd made a mistake but they also knew it didn't define me. And I've never looked back.

"Instead of being an opportunist, I had to strategise. I sat down with my friends and said, 'Guys, boxing is my route, this is what I want to do'. And I was really strong and adamant. I didn't party any more, didn't drink, didn't smoke. It's all or nothing. From court to sport, from negative to positive."

Joshua's is a sobering tale of what might not have been. Born to Nigerian parents in 1989, Joshua soon grew into "a jokey character, big and loud".

"I needed to stay out of trouble," says Joshua, "because I wasn't hard to miss." He set records at school sports days ("you'd see my big, long legs striding across the 100m track"), he played football - good luck marking him - and got himself a music diploma at college. Boxing didn't exist.

"I would have loved to become a footballer but I didn't have the discipline or support," he says. "So it was just a bit of fun, something to do at weekends.

"I was also involved in a little crew. We used to MC at parties, make our own CDs. But that faded out and I got into brick-laying. It paid well, it was active and I was working outside, which I like. It was right up my street.

"I was looking at becoming a builder, learning my trade, starting my own company. But when I moved to London with my mum and I didn't have many friends up here, I got into boxing out of boredom."

Having been dragged down to Finchley Amateur Boxing Club by his cousin, Joshua embarked on a building project of a different sort.

Joshua explains shadow-boxing to his mum

"I was a complete novice in that gym," says Joshua. "But they trained me like I was an Olympic champion. In my eyes, anyway. I went through pain, hard sparring, when I was getting beaten up. But it gave me the discipline I lacked.

"I thought I was doing well until they put me in with an experienced heavyweight. I was trying to slip and slide but I was all over the place - there was no technique, no co-ordination. But failure was a motivation.

"I worked harder, studied more bouts and I began to realise they weren't hitting me as much as they used to. That's when I started thinking, 'You know what, I can get good at this'. So instead of training Monday and Wednesday, I started training Monday, Tuesday and Friday and I started seeing more improvement."

Within two years Joshua was an ABAE senior champion and in the GB set-up. In 2011 he defended his ABAE title and reached the quarter-finals of the European Championships, before clinching qualification for London 2012 with a silver medal at the World Championships in Baku., external

Joshua learned his trade well and he learned his trade fast. Indeed, if there was a tragic aspect of his rise through the amateur boxing ranks it was that London's beleaguered construction game was denied a world-class brickie.

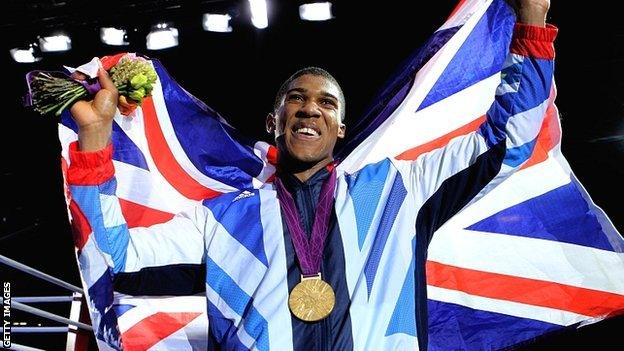

When Joshua became the 29th and last Briton to win gold at London 2012, the public were wowed as much by his humility and child-like wonder in victory as his hulking 6ft 6in, 17 stone frame and wrecking ball fists.

"I was waiting and waiting for the result," says Joshua, who beat Italy's defending champion Roberto Cammarelle on countback in the final. "And suddenly they said, 'In the blue corner...' So I looked across and thought, 'I'm the one in the blue corner!'

"There were a few more phone calls than normal and the lady in the launderette started to notice me. They were good times."

And now, injuries having kept him out of the ring since that glorious August evening, it is time to cast off the uniform and start his own company. The paradox being, never before has he needed such a strong team around him.

In fellow Londoner Audley Harrison, Olympic champion in 2000, Joshua has the perfect example of how not to make his way in the shark-infested paid ranks. Harrison decided to promote himself, did a deal with the BBC and fought sparingly in his first 12 months as a pro, against a string of pitiful victims.

With Eddie Hearn's high-flying Matchroom outfit and Sky Sports's slick publicity machine behind him, Joshua's early fights will be similarly scrutinised. And, being as big and as destructive as he is, there will be plenty of early finishes and much carping about the quality of opponents.

Such has been the lot of any much-heralded heavyweight entering the paid ranks, from Muhammad Ali, who fought a policeman in his first pro fight, to Harrison, who fought a private investigator in his.

The fact that cricketer Andrew Flintoff was briefly rated the 594th best heavyweight in the world last year tells you how small the pool of credible opponents actually is.

But Joshua will hopefully not be headlining bills with any regularity, as Harrison did, and he doesn't seem the type to go in for boasting and posturing. The combination of both should help keep the British public, at least more realistic sections of it, on side.

"Always listen to your mother and father," says Joshua. "They're always right, that's how it goes. Now it's my time to give them an easy life. Who would have known such an aggressive sport could create such a humble character?"

Anthony Joshua shows off his six-pack

- Published11 June 2018

- Published25 July 2013

- Published25 July 2013

- Published26 April 2017

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published12 August 2012