David Millar: Saying goodbye, drugs and Dwain Chambers

- Published

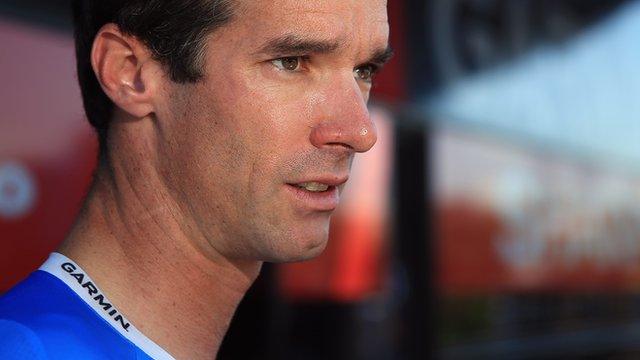

David Millar competes in his final-ever race as a professional cyclist on Sunday

David Millar woke up as a "former" cyclist on Monday, finally freed of the need for speed.

"It's nice to be able to wake up and go and ride my bike and not worry if I am going slow," he said after the final act of his 18-year professional career on Sunday.

For a Malta-born, Hong Kong-raised, Spain-based Scot, Millar's options for a symbolic send-off were endless.

But, for the 37-year-old, the 700-yard dash up a steep Surrey B road surrounded by a hotch-potch of amateurs, lemon drizzle cake and tea urns was the most appropriate way to "close the circle" on his career.

"These races are what it used to be like when I started off, going to random places in the English countryside. It's good to be reminded of where it all began," said Millar.

David Millar factfile | |

|---|---|

Born: 04 January 1977, Malta | |

Road World Championships: Time trial silver medallist (2010, 2001) | |

Grand Tours: 10 solo stage wins across the Tour de France, Giro d'Italia & Vuelta a Espana. First British rider to wear the leader's jersey in all three Grand Tours | |

Commonwealth Games: Gold (time trial), bronze (road race) - both 2010 |

"When you were younger it didn't matter where it was or how many people were there, a race was a race and it had the same excitement, adrenaline and nerves.

"It was a good way to learn the ropes of being a racer. It's different now, it feels nice and homely and there are no nerves and it is a bit of fun."

Millar brought the curtain down on an 18-year professional cycling career at the low-key Bec CC Hill Climb

Fun is not the first word that came to mind watching Millar and the 149 other competitors, including wife Nicole and his father-in-law Nigel, cross the finish line on Sunday.

A fairytale final victory didn't materialise as Millar, riding with a broken hand from a crash at the Vuelta a Espana, finished 21st.

But victory was not the order of the day for Millar, rather the most appropriate of farewells and the chance to quietly reflect on part-famous, part-infamous career.

To some, Millar's name will forever be tarnished by his doping history and the two-year ban he served between 2004 and 2006. A career of huge promise - he secured the yellow jersey on the first stage of his debut Tour de France in 2000 - ruined by the wrong path.

To others, the Scot's fervent anti-doping stance since rejoining the professional peloton means he should be celebrated, not vilified. Millar's initial assessment of his inspirational qualities might be flippant - "probably to people that have messed up, yeah" - but the more measured response is instructive.

"My story is a story of the human condition, we can come back from things," he said. "We can have it all handed to us, then drop it all and then be able to pick it all back up and fix it.

"We all go through things like I have gone through, just on different scales. I hope that helps people.

"I'm very proud of where I have come from. People can know or read my story and see that sometimes the road can be quite bumpy.

"That doesn't mean that it's wrong, it just makes it a bit more interesting and it can often turn us into better people. If it is just smooth and straight it is very boring."

David Millar finished 21st in the 700 yard hill climb in Surrey

Millar, the first British rider to wear the leader's jersey in all three Grand Tours, could never be accused of being boring.

As an erudite voice in the increasingly PR-driven sporting world, Millar has become something of a darling of the British press.

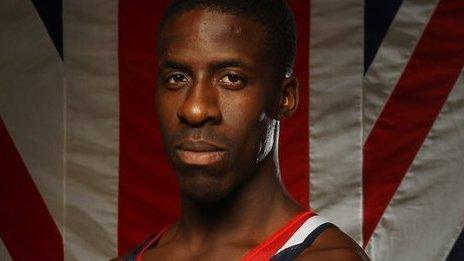

In contrast, sprinter Dwain Chambers - a fellow former drugs cheat turned vocal anti-doping campaigner - is more pariah than on a pedestal.

Born a year apart, their ambition got the better of them and they served part of their respective drugs bans concurrently. Why the different treatment since?

Dwain Chambers, like Millar, was banned from competition for two years for taking performance-enhancing drugs

"Different culture, different background and from a different sport," Millar said. "Athletics is a much more machismo sport with different journalists. I came from a different sport that had a different background.

"He was very much isolated and very much in the British system that was fervently anti-doping. Perhaps he didn't handle it as well as he could have at the beginning.

"It's a shame. I don't think that initial blacklisting he got was necessarily fair. He has done a lot since and he deserves the second chance. Everyone deserves a second chance."

Millar has certainly grasped his. His career did not end with victory at the Bec CC Hill Climb, but he still has a cycling palmares which features 10 solo stage wins in Grand Tours, two World Championship silver medals and a Commonwealth gold in Delhi.

After his final Grand Tour in September - the Vuelta a Espana - and his last outing in GB colours, the recent road World Championships in Spain, Sunday was the third goodbye in a career which Millar sums up with the words "road less travelled".

David Millar at his final race for Great Britain at the World Championships last month

"I could never have predicted how the next 18 years were going to unfold when I started out and it really just became this proper trip, in more senses than one," Millar said.

"It's been a very odd 18 years. It's not something that could be repeated, both because of the time I lived in and the way the professional peloton has changed. The way the sport has jumped between those two different eras has been pretty intense.

"There were three goodbyes in a way. You've got the professional, the national and the local, how it all began.

"It is a long goodbye in that sense. It's nice to have closure."

- Published25 June 2014

- Published14 October 2013

- Published28 November 2011