Bryson DeChambeau: US PGA Championship contender bulks up in effort to win first major

- Published

- comments

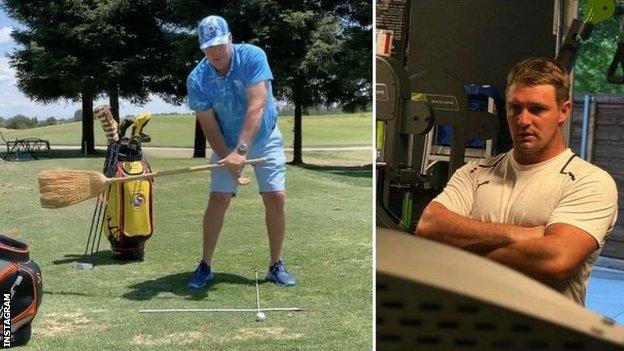

DeChambeau on the left in August 2019 and on the right winning his sixth PGA Tour title at the Rocket Mortgage Classic last month

A version of this article was first published on the BBC Sport website on 4 August, 2020.

Bryson DeChambeau has always enjoyed doing things differently.

Dubbed 'The Scientist', the American's latest experiment was to pile on three stones in nine months to return from sport's enforced break resembling a weightlifter in golf clothing.

The result has been to comfortably out-drive his rivals on the PGA Tour since the restart in June and card four top-10 finishes that include a win at the Rocket Mortgage Classic.

"I've shown people that there's another way to do it," said an emotional DeChambeau afterwards.

"I changed my body, I changed my mindset and was able to accomplish a win while playing a completely different style of golf."

BBC Sport has been told DeChambeau wants to get even bigger, though his muscular physique and monster drives have already got tongues wagging, as has a protein-packed diet that sees him eating more than even the largest England rugby players.

And it has already proved successful as he overpowered the notoriously tough Winged Foot course in New York to win the 120th US Open on Sunday.

'He has always wanted to challenge the norm'

DeChambeau has not become a top-10 golfer on bulk alone - he turned professional in 2016 as just the fifth player to win the NCAA and US Amateur titles in the same year, a list that also includes Jack Nicklaus, Phil Mickelson, Tiger Woods and Ryan Moore.

But adding size has allowed the American to push golf's boundaries.

His success in Detroit saw him record the longest average measured driving distance for any player to win a PGA Tour event, some 350.6 yards, while his average drive of 324.4 yards outstrips anyone on the circuit this year.

The ability to achieve such distance did not surprise his coach Mike Schy, though he says DeChambeau was apprehensive to unleash it at first.

"Even when he was young, I would tell people he had a crank ball," Schy tells BBC Sport.

"If he wants to set his mind to it he can do whatever he wants. Where that limitation is, I am not sure yet."

It has, however, prompted calls from the likes of Nicklaus and Colin Montgomerie to introduce a tournament ball that does not travel as far.

"The reality is he has always wanted to challenge the norm," says Schy. "We have talked about that for a long time, that when that happens people are not going to like it.

"Not until you win a few majors and are number one in the world for a period of time, then maybe all of a sudden people will wake up and go 'OK, maybe we need to look at all this and see it is game-changing'."

Coach Mike Schy has been pleased with DeChambeau's driving and putting this season, but is working on improving his scoring clubs and wedges

The goal for DeChambeau, a physics major in college, was always to find the "most scientifically efficient way" to get the ball in the hole.

Explorations have included cutting all his clubs to the same length, playing with oversized grips, floating golf balls in Epsom salt to check their centre of gravity and using a side-saddle putter.

That putter was ruled non-conforming by the USGA, as was DeChambeau's use of a drawing compass to determine pin locations.

It can sometimes feel to the world number seven that his innovation is being stifled by golf's authorities.

"It's hard when you are trying to do that and there are people of influence pushing back," adds Schy, his coach of 15 years.

"You get a little defensive. You get to the point where you feel 'are these people against me, no matter what?'

"Sometimes it's hard to deal with that - he cares a lot about the game and moving it forward, making it easier for juniors and the normal golfer to play."

Away from the tournament spotlight the pair are free to tinker. Schy gets his students to practise swinging brooms, something he's done since he was a teenager because "we couldn't afford training aids so we just kind of invented stuff".

He once bought a Pirelli racing tyre and, having challenged DeChambeau to not speak for the day, tasked him with hitting it all the way across a 30-foot bunker.

"He did it. He was only moving it maybe an eighth of an inch because it was so heavy and sinking in the sand," explains Schy. "It took him probably four hours, while not talking for the whole day - that was a great part - and he moved it all the way, up and down, up and down.

"If you ask him to do a task and he believes in the task, he will finish it. It could take 10 hours and he'll keep doing it until he gets it."

It is such resilience that saw DeChambeau stick to a rigorous training regime during golf's absence to put his latest experiment into practice.

He added 20lbs during the three-month lockdown to return with a drastically bigger physique.

'He wants to be a Happy Gilmore, hitting 400-yard greens in one!'

DeChambeau posted a clip on social media of him hitting a drive over 200mph

Turning DeChambeau into the 17-stone bundle of muscle he is now has a been a longer process than it appears from the outside.

He began working with Greg Roskopf, founder of Muscle Activation Techniques, three years ago. With DeChambeau experiencing some restrictive movements and pain in his hip and back, the first task was to do an overhaul on his body.

"What Bryson is doing is literally going to change the game of golf," Roskopf tells BBC Sport.

"He's great. He is very intense. He is always looking to be the best. I would say he is interesting in that he's a tinkerer, he's always trying to change things to make it better, which is great."

Roskopf works on the principle "we are only as strong as our weakest link", and set about helping DeChambeau achieve more balance by activating all of his muscles so they could tolerate greater amounts of force, before adding weight to make sure muscle by muscle his movements became stronger.

It helps that DeChambeau has installed the same equipment in his Dallas home that Roskopf uses at his gym in Denver.

"A lot of times the misconception is that weightlifting can cause you to tighten up, especially as a golfer," adds Roskopf.

"If you strengthen these muscles and movements through their full ranges of motion you'll get stronger, maintain your flexibility and if anything the body will actually increase its flexibility.

"That's what's happened with him over time. You can see that transferring now into his swing, his clubhead speed and ball speed, and overall his distance."

It's about being able to tolerate significant force without getting injured. When DeChambeau withdrew from the John Deere Classic in 2018 it was because his shoulder muscles couldn't tolerate the force from his core and he flew directly to Denver to see Roskopf.

Recently he feared breaking down at the hands, wrists and forearms and is doing specific exercises for those. Roskopf says DeChambeau is "very intelligent" and one of a "rare breed" who understands the mechanics of his own body.

So what are the chances of him getting even bigger?

"There are no limitations in his head to where he needs to stop," explains Roskopf. "He's thrown out the weight of 270lbs (19 stone) and wants to keep gaining the mass."

As long as those gains are made in muscle, not fat, and Roskopf does not see any negative effects, such as loss in his range of motion, then he is happy to give the green light.

"If he is maintaining and increasing his strength and maintaining his clubhead speed and the velocity or even improving it, it's going to have positive changes in his distance," says Roskopf.

"I think he wants to be like a Happy Gilmore, he wants to be hitting those 400-yard greens in one. As long as we don't see a negative effect in his overall performance or any increase in potential for injury then the sky's the limit."

The breakfast of a major champion?

DeChambeau makes extensive calculations before each shot

DeChambeau has been fuelling that muscle growth with a 3,000-3,500 calorie daily diet that packs in 400g of protein - the recommended daily intake is around 85g of protein for a man of his weight.

Breakfast contains five slices of bacon, four eggs, toast and two protein shakes, followed throughout his round with a peanut butter and jam sandwich, three more protein shakes, organic protein bars and snacks.

For dinner, he washes down steak and potatoes with two more shakes.

That's what he told reporters last month, adding: "I don't necessarily eat anything or everything I want. With the weight up, I just had to consume a lot more."

Graeme Close, a professor in Sport Nutrition at Liverpool John Moores University and a nutrition consultant for the European Tour, has already had players asking about the DeChambeau diet.

"There's always a feeling it is quite nice when someone challenges the status quo," he tells BBC Sport. "That doesn't mean everyone wants to follow.

"I've not rushed to put my players on to that diet. I wouldn't tend to advise anyone to have more than 40-50g of protein in any one meal. He was having maybe 120g in some meals.

"We know that is not the best way to increase muscle mass, there is a lot of excess there, a lot of wastage."

Close says DeChambeau's reported protein intake is twice the amount a professional rugby player would consume.

"Even those guys would be on 2g per kg body mass, maximum," adds Close, who also works with the England rugby team.

"Most golfers can get their protein needs from food. Having said that, if you are trying to put weight on you do need a calorie surplus.

"If you continue like that, which I have no doubt he won't, we all know where that calorie surplus will end up. It won't be conducive to the sport."

Coach Schy suspects DeChambeau may not maintain his size now the Tour is back in full swing, though his scientific approach will remain.

"He loves the biomechanics aspect of measurements, that's fascinating to him," he adds. "We've always done that stuff, science has always been a big part of what we've done. That's always going to continue."

Whether DeChambeau's latest experiment will prove a long-term success, time and trophies will tell. But it poses the question: will others follow his lead?

"I have had a lot reach out to me, my phone has been ringing off the hook," adds personal trainer Roskopf, who has also worked with the Utah Jazz, Denver Broncos and Denver Nuggets.

"Bryson is just the unique entity in golf who sought it out, committed to it, saw the value and now he is proving that committing to the process can make positive effects in whatever game you're playing.

"He makes my job easy. When he dives in he commits 100%. Some people may seek me out saying 'I want to do what Bryson is doing'.

"Well, you're going to have to work like Bryson has worked and do you have that in you?'

"The problem is time. With Bryson, we put in a lot of time in for him to get to where he is at right now."

From gamer to professional racer: How did simulation lead to the track?

The UK's most unusual festivals: From Cheese Rolling to Gravy Wrestling Championships