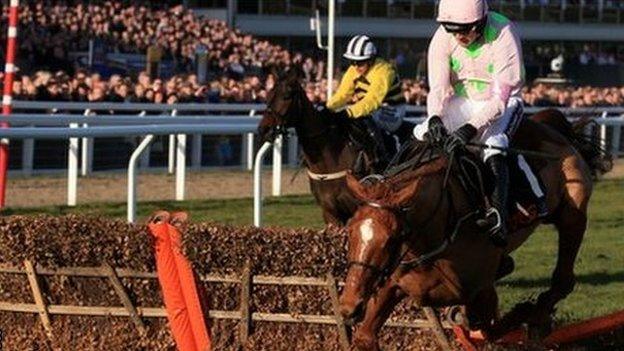

Cheltenham 2015: Horse & jockey: two parts of a racing machine

- Published

"Long Run was always extremely high pressure, but it was always a total thrill," says Sam Waley-Cohen, who he rode to Gold Cup success in 2011

Alone they are nothing. Together, they can be something to which nothing else in sport can compare. Two discrete parts of the same high-speed machine; one brute power, the other the intellect.

This is jockey and mount, man and animal, a relationship like no other.

How is that unique bond formed and maintained? How to communicate in the thundering melee? And why are both changed forever by what they experience as one?

A special relationship - 'You adore some horses'

At Cheltenham this week and Aintree next month, scores of jockeys will ride hundreds of horses. It might seem like the most pragmatic and transient of partnerships. Not to those making them succeed.

"It's much more than a working relationship," says Sam Waley-Cohen, Gold Cup-winning jockey aboard Long Run in 2011 and runner-up at the National on Oscar Time in the same year.

"You build such affection, just as you find doing something in a dangerous situation with a friend. You can't help but have a different level of respect for each other.

"It's not just like playing football. You're both at the very edge of what you're capable of. You're both truly exposed. So you develop a true sense of admiration for these great horses."

It is an essentially practical pairing: can you get me there before anyone else? To flourish, it must also become something deeper.

"We spend a lot of time with these horses, and you get to know them," says Sam Twiston-Davies, retained jockey for eight-time champion trainer Paul Nicholls, and a back-to-back winner at Cheltenham on Wednesday.

Twiston-Davies won the Queen Mother Champion Chase on Wednesday at Cheltenham on Dodging Bullets

"You really appreciate their characters, and you adore some. You spend time together under pressure, and that forges a bond. You don't ever want to see anything go wrong with them."

A union is formed - 'like stepping into a hire car'

No horse is born ready to race or be ridden. No jockey has an instinctive understanding of what makes each horse tick. Each must learn, each must listen.

"When a horse is being broken in, it doesn't know what you're telling it," says Waley-Cohen. "Slowly it learns that each signal means something, like a child learning how to talk or play a game. In a race it's the same. In its first few races it's learning the terms of a new game.

"If it's the same jockey riding it, it adds a measure of consistency. The same message is being conveyed in the same way. And for a rider, if you've never sat on a horse before, you're having to interpret the messages coming from the horse via your experience of other horses. If you already know that horse, you know much quicker what is happening as it develops."

Twiston-Davies, 22, who will ride the appropriately named Sam Winner in Friday's Gold Cup, adds: "The first time you sit on a horse is like stepping into a new hire car. You get an idea of their quirks that first five minutes of riding down to the start.

"But you will have already watched its other races back on video, so you've an idea about how it rides. Sometimes it will match up to those expectations. Other times you have to change your game-plan."

Body as language - 'You are the horse's brain'

Other pairings in sport have it easy. The doubles player in tennis can discuss tactics all they like beforehand. Even as the 2012 Olympic double sculls got under way, rowers Kath Grainger and Anna Watkins could shout final words of encouragement. Jockeys must find more subtle ways.

"Horses are very quick to pick up human emotion or reaction," says Waley-Cohen. "I suspect it's a combination of the tension in your body and your demeanour. On a deeper level, a horse has a sense for its environment beyond 'Is this person on my back kicking me on the belly?'. Much like people will say dogs have a sixth sense, horses can sense the feeling around them.

"There are jockeys who make the horse become part of them, and there are jockeys who become part of the horse. I guess I think of myself as one of those - who tries to become the brain of the horse but listen to what it is telling me. I tend to have the best thrill when you both come together to be more than you both could alone.

"Of all the horses that have given me a thrill, Oscar Time is the one you sit on and think, 'you're a very, very special horse'. He's such a great jumper" - Sam Waley-Cohen

"So before you go into the paddock you have to get yourself into the right state of mind. As soon as you get on the horse you want to transmit that sense of being calm. Because as soon as you're tense and anxious the horse picks up on it and gets wound up itself."

You will often see a rider leaning down his mount's neck before the start to mutter into his pricked ears. When the tape goes up at Cheltenham the eruption of noise from all around - hooves, lungs, roars racing through the grandstands - renders soft words meaningless.

"You're riding a half-ton animal pumped up on adrenaline and running for its life," says Waley-Cohen. "And you have to act as the horse's brain, because the horse's own brain isn't really functioning beyond the basic animal function of 'Escape!'

"It's easy for a horse to be intimidated by somewhere like Cheltenham or Aintree. Very few animals have experienced that sort of noise before. It's the tone in your voice that is the number one thing the horse picks up. When you're in the heart of the battle, you're roaring at the horse.

"You're throwing everything you have at it - a combination of tone of voice, volume and swearwords. The horse isn't used to such noise coming behind them; that change of environment is what they react to."

The good listener - 'like driving an old F1 car'

If Lewis Hamilton requires feedback on the performance of his Mercedes in the ear-splitting chaos of a Grand Prix, a bank of computers provides both him and his engineers with the most precise data. For a jockey aboard a flat-out thoroughbred it is a far more visceral process.

"If you looked at the old Formula One cars, you didn't get a lot of data coming out of those - it was all about the noise coming out of the engine, how the chassis felt," explains Waley-Cohen.

"Riding a horse is like that. If you know your horse you can get a sense of what they've got left in them, how they're travelling, how they're jumping, how settled they are.

“If you fell off Mad Moose you could guarantee he'd go back to the stables and you'd find him with his head in his feed. He knew what was going on. If he didn't want to do it, he wouldn't" - Twiston-Davies

"Part of that information you pick up is from the horses around you. You get a sense of how hard they're pulling, how much energy they're expending. That gives you a benchmark for how much yours is doing.

"That's where race-craft comes in. That and knowing what the horse is capable of. Can I ask it to do this? Do I ask it to do this now, or do I wait for later in the race to sacrifice that energy?"

So you're thundering along with clods of turf flying up and the jumps coming quick and fast. Your mount isn't. How to drive them on?

"If you're not jumping, mix it up. You get them out of their rut. If you're down the inside you might go out; if you're on the outside, you might switch it in to get it more involved."

Kidology - 'Help them find another gear'

Should Chris Froome snap a chain or blow an inner tube on his Pinarello Dogma halfway through a mountain stage, a Team Sky car will have a new wheel or bike to him in seconds. For National Hunt jockeys there are no such second chances.

"It's like a 1500m race on the track," says Waley-Cohen. "Because you're always on the edge of what they're capable of, it's only modest changes that give you a lot of information.

"If the horse is starting to struggle you realise straight away because they come off the bridle. You're feeling like you're having to ask too many questions at the fences. If it's cruising you'll be meeting every fence easy-peasy, the reins hard in your hand."

To the last few furlongs. The race is there to be won - but just when you want to make your move, the horse backs off.

"Horses have their own sense of how they're doing in a race," says Waley-Cohen. "If it's being held up it knows it's going well. So if the horse is getting tired and coming off the bit (in its mouth), so that the reins in your hands are starting to get loose, you shorten up your reins to get it back on the bit and almost kid it into thinking it's running better than it is. It can help them find another gear.

"Sometimes they just hit a flat spot. So the question to you is whether you let it have 10 strides to get itself together again, or will that cost you the race so you have to push it again? You have that split-second decision."

Personality - 'We believe they recognise us'

It remains one of the iconic moments from the BBC's Sports Personality of the Year: three-time National winner Red Rum, in a different studio hundreds of miles away, coming alive as he heard the voice of his jockey Tommy Stack - who took over in 1976 and '77 from his original mount Brian Fletcher - coming down the line.

'Rummie' was a special animal, his relationship with Fletcher pivotal to the fairytale successes of 1973 and '74. Can most ordinary horses truly tell the difference between the various small, hard men who sit in their saddle?

"I think so," says Twiston-Davies, who rode Hello Bud in the 2010 Grand National when he was just 17 years old. "You never really truly know what a horse is thinking, but if you go to get them in from the field they might come to you, whereas if someone else goes they won't come. We like to believe as humans that they recognise us."

"They really do have different personalities," says Waley-Cohen. "There are the ones that try so hard and give you absolutely everything, the ones that couldn't care less and would happily stop and eat the grass.

"Knowing those different personalities and how to get the best out of them is half the fun of the sport. And it's only when a horse is in the thick of a race that its personality has any chance to be expressed.

"Because its whole being is to race. The rest of the time is the artificial situation where it's being pampered, eating and relaxing. That isn't what a race horse is. It's a finely tuned animal that lives to race."

Love and death - 'You really are a team'

How much does a jockey really care for the horse that carries him home? Isn't this just a marriage of convenience, a relationship quickly forgotten by both if it turns sour?

"No," says Waley-Cohen with vehemence, while Twiston-Davies grows noticeably emotional at the mere mention of one of his long-term rides. Little Josh fell four fences from home in the 2013 Topham Chase at Aintree, suffered a fractured shoulder and was later put down.

"Little Josh (left) loved Aintree. He'd won there before and it was something he adored" - Twiston-Davies

"I loved Little Josh to pieces," he says. "I got my first big winner on him, he was an excellent horse and I loved riding him.

"The thing I try to remember is that he was doing the one thing he loved more than anything else - racing. Until that fall he was having the best time of his life and was very happy. I know too he was gone very quickly, which helps ease the pain a little, but we will always miss him."

"There's an element of selfishness there, your own hopes and dreams going with them," admits Waley-Cohen. "And there's a sense of loss for all the people who put so much hard work and effort into the horse.

"In a race you see just a tiny moment of time with horse and jockey. Think of the hours of work and love and energy that go into getting that horse there. That sense of loss and sadness is really quite permeating.

"As a horse and jockey you really are a team. There are very few environments in the world where a human can come together with an animal and become something so much greater than themselves. When it works, it's truly special."

- Published4 April 2014

- Published11 March 2015

- Published10 March 2015