Ruby Walsh: At home with a family that lives and breathes horse racing

- Published

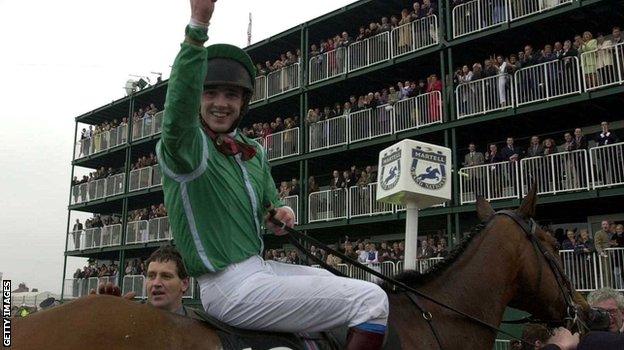

Ruby Walsh has ridden some of National Hunt racing's best-known performers including Kauto Star, Denman, Master Minded and Big Buck's but victory on Irish chaser Papillon to win the Grand National at his first attempt in 2000 remains his favourite achievement

It is a career that has delivered over 2,000 race victories.

Now aged 38, Ruby Walsh is an elite jockey who has been at the forefront of his sport for over two decades - and has a particular attitude to the physical pain his occupation regularly delivers.

As the National Hunt season gets under way, BBC Sport travelled to County Kildare, Ireland, to talk to the two-time Grand National winner, his sister Katie - herself a jockey - and his father, Ted, a trainer and television pundit.

The moment that tops riding Kauto Star

It took a total of nine minutes and nine seconds and, some 17 years later, it remains the greatest race of Ruby Walsh's career.

The 2000 Grand National was the then 20-year-old's first attempt at the daunting course of more than four miles; a first go at navigating its notorious fences, such as Becher's Brook and the Canal Turn.

On board Papillon - a 10-1 shot, trained by his father, Ted - Ruby won a thrilling race, external by just one and a quarter lengths from Mely Moss.

More success would come in later years. Another National triumph on Hedgehunter in 2005 and then multiple wins in the Cheltenham Gold Cup and the King George VI chase on the legendary Kauto Star.

But it is that April afternoon in 2000, cheered to the rafters by a huge Aintree crowd, that he insists can never be beaten.

"You can go to the Gold Cup on Kauto Star and he's 6-4, nearly even money, to win. And even though it's the Gold Cup, he's the best horse.

"You do your job right, you nail this and you've got a great chance of winning.

"In the National, it's unique. It doesn't matter if you're even money or 20-1, you basically have the same chance as everyone else of getting to the back of the third fence."

Richard Conway joins the Walsh family around the breakfast table

At the family breakfast table, after a morning on the gallops with Ted's current crop of horses, the conversation flows with talk of how the current prospects are faring and the weekend's football results.

The discussion soon returns to the Grand National and Katie, who finished third on Seabass in 2012, is in agreement with her brother on its timeless appeal.

She says: "That's what makes it special. You line up there, 40 of you. And I'm not kidding you, everyone at that start, and I don't care what you're on, everyone says 'I've got a chance of winning this'."

"I'll tell you what's a worse thing," says Ruby, interjecting.

"When you line up at the start and you think 'I've not a chance of getting to Becher's."

The pair erupt in laughter at their memories of Aintree and their smiles reveal the passion they have for both the race and their sport.

'Cat? Elephant? Or Constantinople?'

The walls of Ted's kitchen carry portraits of the great horses the family has nurtured and trained over the years. Papillion, naturally, takes pride of place.

This is not a museum to past glories though. The talk over the scrambled eggs, toast, bacon and pots of tea prepared by Ted's wife, Helen, is about the promise of the new National Hunt season.

"This is an exciting time of year," says Katie.

"All the horses are back in and there's new recruits. So you don't really know if something's good or if everything's good. It's nice to find out what you have for the rest of the season."

Father and son deep in conversation at Leopardstown in 2013

Ted, in his own inimitable way, puts the anticipation of discovering if there's a potential Cheltenham or Aintree contender in the yard somewhat differently.

"You have a fair idea at an early stage," he says.

"It's like kids going to school. One fella stands out very early. He picks up the teacher's teachings quicker than the others. He can spell 'elephant' while the others can spell 'cat'.

"All of a sudden you think, 'he's a bit exceptional'.

"Now the others may catch up. He may not get beyond the stage of 'elephant'.

"But sometimes, before you know where you are, he's spelling 'Constantinople'. That's when you know, this one's a little bit different to the rest."

There are only ever 16 horses at one time in Ted's yard, who also buys and sells his equine stock to make a living.

He has two horses in training from the famous Irish owner, gambler and philanthropist JP McManus but there's recognition that some trainers, like his countryman Willie Mullins, operate on a different level. "We're a cornershop to his Tesco's," Ted remarks.

Ruby Walsh rode Kauto Star to Cheltenham Gold Cup victory in 2007 and 2009

The finances are crucial in what can be a tough business, especially in leaner years. However, it is the thrill of winning a big race that truly separates this trade from a regular nine to five job.

"It's the accomplishment, the buzz, the thrill of doing it. The spin-off afterwards financially might be good but that's not what you're thinking of. You're thinking, 'I've prepared this horse for this big day and it's landed'. That's doesn't fade. It never goes away," says Ted.

Many would see getting up at dawn every day to muck out stables and prepare the horses his owners have entrusted to him as hard work.

Passion for racing transcends such thoughts, it seems.

"We're all very lucky, we get up every morning to do something that we absolutely love," says Katie.

"There's a lot of people who hate their jobs, don't want to go to work and are constantly looking for a way out.

"Some people go through this life and all they want to do is milk the system and get what they're entitled to. And I feel sorry for them. They've no drive, no ambition. It's a sad existence."

'When your spleen is gone, it's gone. Move on'

Somewhere amongst the horses' hooves is Ruby Walsh, having fallen off Kauto Star during the 2006 Cheltenham Festival

It's a work ethic that extends to a shared attitude to pain and dealing with injuries, a common occupational hazard when steering a horse over the jumps at speeds of up to 40mph.

Ruby has sustained multiple broken bones throughout his career but sees it as just another obstacle he must clear in order to sustain success.

"There are loads of things that people do that are high-risk," he says.

"Would I join the army or the navy? You must be off your rocker."

Losing your spleen, which occurred after falling at Cheltenham in 2008, would make many less hardy personalities think twice about carrying on. The fact that he was back riding within a month of the operation surely demonstrates that jockeys are a different breed from other sportsmen and women.

"When your spleen is gone, it's gone. It's not coming back," he says.

"You don't need it. It would have been worse if it was kidney or my bladder. But it was my spleen that ruptured. They just took it out. Move on. It's not a huge drama. Take an antibiotic and a few injections and away you go."

It would be easy to view this as a gung-ho, macho attitude. Instead, it's clear this way of thinking is the cold reality, in both sporting terms and economically, of what it takes to survive at the very top.

"As long as it's not your brain or your neck, the rest will heal," Ruby adds.

With a glint in his eye there's a suggestion other sports could benefit from that mindset.

"When you look at the massive contracts in other sports, do you make it more 'pay for play'? Do lads suddenly stand up a little bit quicker? Who knows?"

Katie Walsh leads on Seabass over the final fence at the 2012 Grand National before being beaten into third by Neptune Collonges and SunnyHillBoy. This is the best finish by a female jockey in the race.

Staying fit, surviving the falls and recovering quickly when injured have helped him land some of the biggest prizes in jump racing, on some of the sport's most memorable horses.

Kauto Star, Denman, Hurricane Fly, Quevega, Vautour, Hedgehunter, Annie Power, Un de Sceaux and Big Bucks are just some he has ridden into the history books.

And yet, in common with other athletes at the very top of their discipline, there is an insatiable appetite and drive to keep on winning.

What is left now to achieve?

"More," is the succinct answer.

"I never set out to achieve specifically what I've achieved. I was hoping to ride a winner, and then to ride another one and then as many as I could. You keep rolling on and on and on. You don't want to stop. There's no target. It's just to keep going and trying to get a notch further ahead."

As for Katie, there's a sense of unfinished business when it comes to the Grand National. A third on Seabass in 2012 was perhaps a taste of what is possible in the future.

"I'd love to win it. Of course I would. Who wouldn't?" she smiles.

The new season awaits with all its twists and turns. But no matter what happens, the Walsh family's enduring love for racing is a certainty.

- Published3 November 2017

- Published21 October 2017

- Published31 October 2017

- Published31 October 2017

- Published30 October 2017

- Attribution

- Published31 October 2017