Leon Edwards: UFC fighter's rise to world champion & escaping his 'darkest years'

- Published

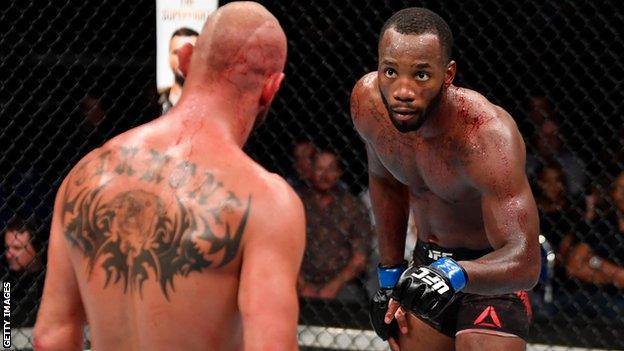

Edwards says he wants to inspire others to transform their lives

It happened about four years after Leon Edwards moved to England.

He, his mum and little brother had said their goodbyes in Jamaica and come to Birmingham to start a new life.

They'd left their old home behind - a one-room wooden shack with a zinc roof in a poor part of Kingston where "hearing gunshots was normal".

Edwards had his own room now. That's where he was when the phone rang one night at 2am in October 2004, aged 13.

The boys' father had been the first to come over to England from Kingston. He'd sent for them to follow, but they didn't live together.

Edwards' mum picked up the phone. He could soon hear her crying.

"I knew what he was involved in, so I knew eventually something would happen to my dad," Edwards says.

"When it's a late phone call you know it's something bad. It was a traumatic situation. It wasn't like he died in his sleep - he got murdered.

"It was like a spiral effect; it definitely made me more angry and more willing to partake in that life. It pushed me into a life of crime."

Edwards, now aged 30, still does not know the full story behind his father's death, just that he was shot and killed at a nightclub, over "something to do with money". He'd been involved in gang crime back in Kingston and, growing up, Edwards often found himself exposed to its dangers.

Over the next few years - the "darkest" of his life - Edwards too was increasingly drawn into the world of gang violence in Birmingham.

But he would get out, forging a path in MMA against the odds which has culminated in him winning the sport's biggest prize - a UFC world title.

Edwards was born and grew up in a small neighbourhood in Kingston, Jamaica with his mum, dad and younger brother, Fabian.

He would play football with his friends, build and fly kites in the Caribbean breeze and climb trees to pick mangoes.

But there was also a dangerous side to life - one Edwards says he could not imagine his own children having to experience.

Edwards' father was the leader of a local gang. He was known as The General. Edwards was so often exposed to gun violence in his neighbourhood that he became desensitised to it.

"There were shootouts around me," he says.

"You had to run and hide. It's weird because you kind of get used to it, living in this mad warzone, you know? I've got a son now who's nine and I couldn't imagine him in that environment.

"But at the time you hear gunshots. You're like 'OK, no-one got hit and no-one died', so you're back out playing again. It just becomes normal."

By this point, when Edwards was nine, his parents had separated and his father was already living in London while still helping to take financial care of the family from abroad.

His father's decision to move the rest of the family over to the UK - to Aston in Birmingham - was supposed to represent a new beginning. Edwards found it difficult from the start.

"You don't want to move because all your friends are in Jamaica. You don't want to leave them, and at the time I was upset," he says.

"You're also an immigrant coming to a new country, but it's still better than worrying about getting shot by a stray bullet or whatever."

Edwards recalls getting into fights with the other kids at school, who would pick on him because of his Jamaican accent.

His willingness to fight is where his nickname 'Rocky' comes from - a reference to the boxer from the movie that still endures.

Soon things would take an even more troubling turn.

"There was a big gang thing at the time in Birmingham, the Johnsons and the Burger Bars," Edwards says.

"They were rivals and violence constantly broke out between both sides.

"I got involved from school. Obviously you're in the same neighbourhood and you go to the same school [as the gang members].

"The older guys, the younger brothers, all at the same school, and you get used to hanging around with them and it just trickles into that."

Edwards was 13 when he learned of the death of his father. He says it was a tipping point that pushed him further into that life.

"I had a shorter temper, I was more angry and I ended up in more fights," he says.

"There were a few things I did during this time that I truly regret. It's hard to believe it was me who did it. I don't like talking about it.

"I've been in situations where, I wouldn't say I feared for my life, but life-threatening situations. We did what all gangs do. Sell drugs, there were robberies, shootings and stabbings.

"I was arrested a few times, for fights and having a knife. My mum had to come to the police station many times to get me out.

"I knew what I was doing was breaking her heart, but I just kept doing it because your friends are doing it and as a teenager you're just involved.

"At the time your brain is so diluted and so focused you think this is life, and this is your world. You can't see outside of it."

Edwards has won 12 of his 15 UFC bouts

One day, at the age of 17, when Edwards was walking to the bus stop with his mother, she spotted a gym above a DVD rental store offering training in mixed martial arts.

Edwards joined. He hadn't even heard of MMA before. His perception of fighting was so skewed by gang culture that the idea of a fair fight, played out in a competitive, sporting context, felt alien to him.

"It was odd because at the time I used to think that fighting was, not weird, but I'd never straight nose [have a fair fight with] somebody, you know?" he says.

"[Gangs] are more likely to stab you. That was the mentality."

After attending a few classes, Edwards' coaches told him he had a natural talent.

He soon started winning awards, and the positive reaction he got from his mother pushed him to achieve even more.

"I could see my mum was proud of me, when I was bringing home trophies and that, and that's what kept me at it," Edwards says.

"If you did something negative [in gangs], everyone supports you, then if you do something good I realised you get the same praise, so I was thinking 'well I might as well do good then'.

"I was thinking I should enjoy my life and not have to look behind my back at people trying to stab me, see the world - and that's what I did. I put all my energy into training at 17 and just never looked back."

At the age of 18 Edwards made his amateur debut, which he won by submission, with a victorious professional bow coming just over a year later.

By the age of 23 he'd signed with the UFC, where he has 12 wins from 15 fights.

He hasn't suffered defeat since losing against current pound-for-pound number one Kamaru Usman seven years ago - the same opponent he beat for the welterweight title at UFC 278 in Salt Lake City, Utah last August.

In doing so he became Britain's first champion since Michael Bisping in 2016, and only the second in UFC history.

Edwards defends his title against Usman at UFC 286 in London on Saturday 18 March.

Usman, 35, and Edwards at a press conference before their 20 August fight

Edwards has always been reserved when talking about his story. Unlike a selection of other fighters, he has never embraced the 'gangster' narrative.

Instead he recognises the power behind his remarkable transition - and wants to help others who are looking for change. He credits sport with potentially saving his life.

"I didn't want to glorify it, I didn't want to come across as this gangster," he says.

"I wanted to be a better person than my story was. The more my profile grows, the more I succeed, the more I want to help other people. I want to show people now it's not where you start, it's where you finish.

"In the UK, knife crime is such a big thing, I've lost friends to it, been involved with it, so if I can go back and help someone and show them a different path, I'm willing to do that.

"One of my friends, he went to prison, got stabbed and died. Some of them have made good and work and stuff, but most of them are still doing what they're doing.

"So yeah, I take it from that - [without MMA] I'd either be in prison, dead or working a 9-5.

"I'm 100% relieved. Not just me but my family too, you know. It would be sad for my mum to have a husband that got killed and then a son that got killed.

"I always had a feeling I could be better and there was more to life, but I didn't know how to get it. There was nobody around me with a blueprint to success so I didn't know how to achieve it.

"That's what I'm saying: if I do it - if I become champion - it shows everyone else what's possible, too."

A version of this article was first published on 18 August, 2022.