Jeff Novitzky: From taking down Lance Armstrong to cleaning up the UFC

- Published

Novitzky (right) congratulates fighters with a commemorative jacket when they pass 50 drug tests in the UFC

When Lance Armstrong admitted to cheating during all seven of his Tour de France wins in front of a worldwide television audience in 2013, it brought mixed emotions for Jeff Novitzky.

For three years, American Novitzky, who was a federal agent at the time, had been leading a criminal investigation into Armstrong for the use of performance-enhancing drugs in cycling.

Armstrong never faced criminal charges because the investigation was eventually shut down by the United States Attorney in Southern California, but the American's confession to US chat show host Oprah Winfrey that he had been doping led to him being stripped of his titles.

Novitzky says no explanation was given for the investigation being shut down, which was "unusual", and speculates that "some type of political favour" may have been called in.

"While that was disappointing [the investigation being shut down], ultimately I think the same end game was met and that was, not just the exposure of Armstrong and US Postal Cycling Team, but all of professional cycling and what was really going on there," Novitzky tells BBC Sport.

"You look at him and while you may say he didn't have to pay for it after the criminal investigation was shut down, I don't think that's accurate.

"He was stripped of all his titles, he still today is considered one of the biggest falls from grace in professional sports, and he will forever have to live with that legacy."

Armstrong on drugs, history and the future

Novitzky's work in the Armstrong case played a big part in him landing a key role at the UFC in 2015, where the 54-year-old has helped implement one of the most comprehensive anti-doping programmes in professional sports.

Novitzky has adopted the nickname the 'Golden Snitch' due to his role in exposing drug cheats, and to this day UFC president Dana White introduces him to people as "the guy who took down Lance Armstrong".

"I kind of embraced it [the nickname], and I think a lot of people appreciate when you have a little bit of a sense of humour," said Novitzky.

"You know, snitch isn't necessarily the best nickname to have, but at least it's a golden one."

'The importance of MMA drug testing exceeds every other sport'

The doping landscape in the UFC is unrecognisable to what it was seven years ago when Novitzky came on board.

After joining, the UFC hired the United States Anti-doping Agency (Usada) as their independent anti-doping agency.

Novitzky says Usada were chosen because they "only care about clean sport" and "don't care about the success of the UFC, revenue-wise and business-wise".

Usada have full control over how much fighters are tested and when, and have the power to test athletes at any time, 365 days a year.

All fighters under contract with the UFC are eligible for testing by Usada, while athletes who remove themselves from the pool are required to re-enter it for six months and provide at least two negative samples before they can compete again.

Last year, Usada tested UFC fighters 4,352 times,, external which is almost double the 2,289 tests they conducted one year into the programme in 2016.

Before Novitzky and Usada's involvement in the UFC however, athletes were only subjected to Athletic Commission testing, which would usually take place in the week of a fight, rather than all year round.

Novitzky says if fighters were thinking about cheating, all they had to do was make sure any drugs had cleared from their system by the time Athletic Commission testing came around.

"In this sport - in MMA - the importance of anti-doping and drug testing exceeds every other sport by far I believe," said Novitzky.

"These are the most talented martial artists on the planet and I think it was inevitable that had things progressed as they were before this programme, we were gonna run into something really bad where someone was going to seriously hurt their opponent."

Novitzky says eliminating the doping culture in the UFC has helped grow the popularity of the sport and brand.

"I think in many aspects, whether it's the kits, the equipment we're wearing, sponsorship, anti-doping, the goal when I came here eight years ago was to mainstream this sport," he said.

"We don't want this to be known as this niche freak sport, we're going to do what other professional sports are doing and certainly that freak show nature of an enhanced athlete, all on artificial hormones and that, wasn't a look if you're trying to mainstream sport.

"I think there are many factors but I do think [the drugs programme] is a contributing factor to the success of this sport."

Novitzky adds that he has received "overwhelmingly positive" feedback from fighters on the anti-doping programme.

He says before Usada's involvement, many athletes chose to dope to "level the playing field", as a minority were using drugs for enhancement but the rest didn't want to be left at a disadvantage.

"When I talk to athletes recently it's that relief like 'I don't have to make that decision anymore' [to dope]," he said.

"Most of our fighters see and realise 'hey, I don't have to worry now about what I'm doing to keep up with my opponent because what I'm subject to. Testers can come to my house at any time and my opponent is subject to that too'."

'Cheaters are always one step ahead - but we've narrowed the gap'

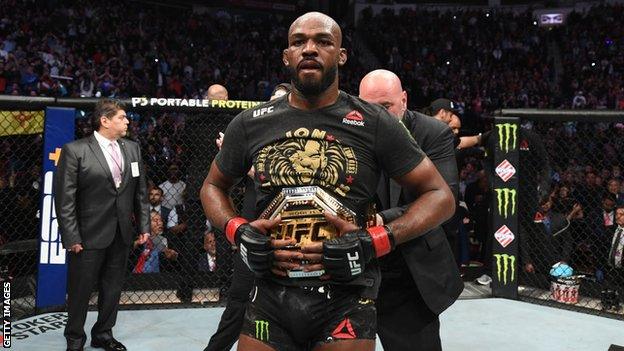

Jon Jones has been stripped of the light-heavyweight title twice for failed drugs tests

Despite the success of its anti-doping programme, the UFC still faces many challenges.

Perhaps the biggest one is keeping up with advances in science, which Novitzky describes as a "cat and mouse" game.

When testing athletes, substances are only uncovered when they are specifically tested for, so any potential new or altered drugs may go undiscovered.

Novitzky says parts of the pharmaceutical industry, or people he calls "garage chemists", are doing experiments behind closed doors, working on new doping techniques all the time.

"Usada realises this, that anti-doping has historically been a reactive process, and they understand the need for proactivity," said Novitsky.

"One of the things they do is they interact with the pharmaceutical industry, and they are made aware of new drugs coming down the pipeline that maybe aren't even yet approved for human use. That's one example of the proactivity.

"The nature of the beast is the scientists, the athletes trying to get over and cheat are always going to be a step ahead, but I do believe recently the gap is narrowing."

Novitzky points to Usada's biological passport programme as another example of narrowing that gap.

The programme keeps records of reactions in athlete's bodies which drugs can induce, such as raised cholesterol or liver enzyme levels, so even if a specific drug may remain undiscovered, the effects it has on the body would be detected and investigated further by Usada officials.

'I don't get much joy out of it'

Some of the most high-profile fighters to be caught doping by Usada in the UFC include former champions Jon Jones and TJ Dillashaw.

Ex-light-heavyweight title holder Jones has served two suspensions in 2016 and 2018 respectively for failed drugs tests, while former bantamweight champion Dillashaw was banned for two years in 2019.

More recently, Bobby Green, who headlined a fight card in February against currently lightweight champion Islam Makhachev, was banned for six months last July for testing positive for Dehydroepiandrosterone.

Novitzky says he experiences a "mixed bag" of emotions when a fighter tests positive.

"When you catch someone intentionally cheating, that's the purpose of this programme, but I don't get much joy out of it," he said.

"When I see these positive tests come in I reflect inwards, saying 'what did I not do right to convince this athlete that if they were going to go down this road, they were going to get caught'?"

"And so, I'm never clapping or jumping for joy, I think the disappointment side far outweighs the satisfaction side of this."

Do longer prison sentences reduce crime?: Bad People goes in search of answers

The champion of two courts ignored by the world: Ora Washington fought to make her name in racially segregated America