Beamon still a step ahead of the rest

- Published

Few things have stood the test of time since 1968.

The White Album by the Beatles is one obvious exception, with its wondrous myriad musical styles, but in the world of athletics a mixture of professionalism, new technology and dietary refinements have ensured that everything has been gradually superseded.

Except that is in the long jump, where Bob Beamon's 44-year-old landmark remains, like a beacon of sporting achievement, as the oldest Olympic track and field record.

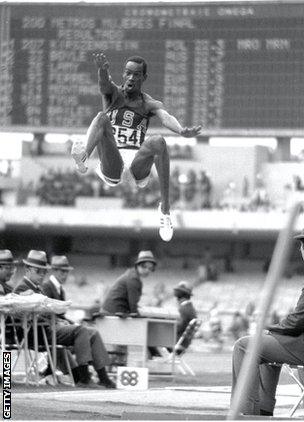

On 18 October 1968 in Mexico City, Beamon leapt 8.90metres to beat the existing world record - set by Igor Ter-Ovanesyan a year earlier - by a remarkable 55cm.

In the previous 33 years, the record had been improved by just 22cm - from the legendary Jesse Owens's 8.13m in 1935 to Ter-Ovanesyan's 8.35m.

Beamon's jump has only been bettered in competition since at the 1991 World Championship in Japan.

Carl Lewis eclipsed it by one centimetre, although the jump was wind-assisted and not classed as a record, but another American, Mike Powell, later set a new mark of 8.95m.

However, in Olympic competition even the great Lewis could get no closer than 18cm of Beamon's record.

By contrast, the triple jump record changed hands five times in two days at the Mexico Games and was broken in three successive Games between 1988 and 1996.

Britain's Lynn Davies won Olympic gold in 1964 with 8.07m but famously remarked that Beamon "destroyed the event" with his exploits four years later.

"It was a very unfair Olympic Games in many ways because, being at 8,000 feet, it was a rarefied atmosphere," said the Welshman, who carried the British flag in the opening ceremony in Mexico but could finish only ninth with 7.94m.

He told BBC Sport: "For the explosive events we knew there would be world records because there was less air pressure and resistance. Many records were exceeded because it was at altitude."

Also in 1968, the 100m went below 10 seconds and the 200m was sub-20 seconds for the first time in Olympic history, yet that double was not repeated until Lewis achieved the feat at Los Angeles 16 years later.

Recalling the build-up to Mexico, Davies added: "My win four years earlier had been a big surprise because I was an outsider, but, going into Mexico, the world record was 8.35m and I had jumped 8.24m in that summer, which ranked me in the top three in the world. So there were four of us capable of winning: Beamon, myself, Ralph Boston and Igor Ter-Ovanesyan.

"We thought 28 feet was the next barrier, which was something like 8.54m. We knew Beamon was capable of that but we never thought he had the technique and the consistency to strike the take-off board with accuracy."

And of the famous leap itself? "They couldn't measure the jump because the measuring apparatus only went out to about 28-feet something.

Lynn Davies on how Usain Bolt would fare in the long jump

"The field referee had to come over and use a steel tape, so it took about 15 minutes between the time of him actually landing, to the scoreboard showing the distance of 8.90.

"None of us could convert that, but it turned out he was over 29 feet, so he'd missed out the 28-feet barrier altogether.

"When he jumped the wind was behind him - not a strong wind but a couple of metres per second, as it did in Mexico in those tropical conditions.

"In those 15 minutes, it began to rain and the wind turned right around and was now blowing into our face, so we were faced with an incredible new world record in the first round and deteriorating weather conditions!"

Beamon, now a graphic designer, never again jumped beyond 8.22m after Mexico and retired before the next Olympics in 1972.

His Olympic legacy lives on, however, and does not look like being broken in the distinctly unrarefied London air this summer.

Irving Saladino, the 2007 world champion who became Panama's first Olympic champion with victory in Beijing, managed only one valid jump - a modest 7.84m - at last year's World Championship in Daegu.

Australian Mitchell Watt recorded four of the best five jumps in 2011, the longest of which was 8.54m.

"At the moment there is nobody on the horizon but no doubt somebody will come along," Davies said. "As the sport expands globally and more talent is discovered, somebody will come along with exceptional physical abilities."

Two Britons are expected to be involved in London, Chris Tomlinson and Greg Rutherford.

"London represents a great opportunity for either of them to get a medal," Davies said. "I think it will take between 8.40m and 8.50m to get a medal and between 8.50m and 8.60m to win the gold.

"Greg and Chris are capable of between 8.40m and 8.50m. It would be fantastic for them to get a medal because for many years the long jump languished in this country.

"The thing about the Olympic Games is that the final imposes special pressures because there is so much at stake. Whereas you would imagine it might bring out that extra 10% in a performer, in many circumstances it worked the other way and distances haven't been as far.

"Each human being has got their own ceiling of potential. No matter how hard I trained, there is no way I could have jumped that far.

"That's the unfair thing about the sport. Some people are born with special abilities.

"Carl Lewis is the only guy I think who would have been capable of doing it in the Olympic Games. A Carl Lewis only comes along every couple of generations, so we may well go through the next few Olympiads with that record still standing."

- Published23 December 2011