London 2012: Olympic moments that stopped the world

- Published

Some of the most memorable moments in sport have taken place in the biggest arena - the Olympic Games.

In a programme to be broadcast on BBC Radio 5 live at 1930 BST on Thursday, the focus will be on iconic pieces of sporting theatre that made headlines at the Games.

Here is a selection of those that will be featured:

Beamonesque

Huge? It was massive.

When Bob Beamon stood on the runway waiting to make his first attempt in the 1968 long jump final, few would have predicted that not only would he break the world record but that he would obliterate it.

The previous mark was 8.35m but, in the heat of Mexico City, the United States athlete came out of the sand having leapt to 8.90m.

Jaws dropped, commentators flapped. Even Beamon took a while to realise what he had achieved.

"It was shocking, absolutely shocking," said team-mate and fellow competitor Ralph Boston, who had once held the record.

"After they measured the jump, Bob came to me and asked, 'How far is that?'

"I said to him, 'Bob, that's more than 29ft.' He asked, 'Are you serious?' and I said, 'Yes, I am.'"

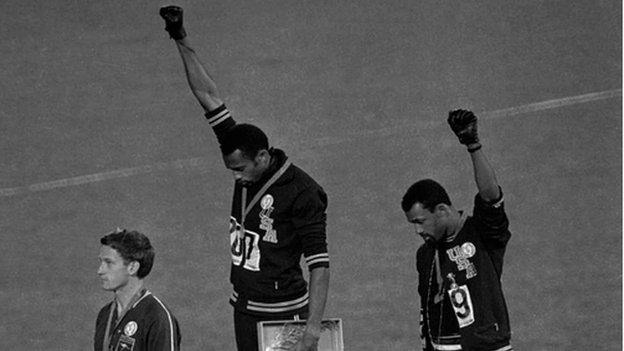

Black Power rocks the US

Mexico Olympics 200m bronze medallist John Carlos recalls the political statement he made in 1968

Politics and the Olympics have not been the most comfortable of bedfellows.

In 1968, the United States team were buoyed by the miraculous achievements of golden boys Beamon, Dick Fosbury and Jim Hines.

But they were left rattled by another successful pair, when Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their black-gloved fists in the air after receiving medals for their performances in the 200m.

Why? The team-mates, who also wore black socks and no shoes, wanted to highlight the poverty of the American black community.

The salute, according to Smith at the time, "stood for the power in black America".

The statement was frowned upon by the International Olympic Committee and was deemed "a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit".

The US team gave Smith, who won gold, and Carlos, the bronze-medal winner, 48 hours to pack their bags and leave the country.

"It was necessary to make a statement strong enough to reach the ends of the earth, but also one that was non-violent," recalled Carlos.

Barcelona's golden arrow

As far as 'lighting the Olympic cauldron' moments go, 1992 Barcelona was among one of the most memorable and certainly the most audacious.

The 67,000 packed into the Estadi Olimpic Lluis Companys were left stunned as they watched the lit arrow of Paralympic archer Antonio Rebollo fired high over the heads of spectators and seemingly land inside the cauldron, which was consequently ignited.

In fact, what happened is that the arrow continued to fly out of the stadium. But as a visual spectacle it worked, with the Catalan city setting the bar high for future Olympic hosts.

"Antonio was 62 metres from the cauldron for that shot," said Ric Birch, who was the executive producer for the opening ceremony.

"No-one in the world could have fired the arrow in the air and have it drop down into the cauldron.

"If we fired an arrow into it then the gas pipes would have exploded. The trick was to fire it within a two-metre distance of the top of the cauldron.

"Antonio pulled off that shot over and over again in rehearsals."

The perfect Olympian

Nadia Comaneci remembers the impact she had on gymnastics in 1976

At the 1976 Olympics, 14-year-old gymnast Nadia Comaneci achieved something all sports starts strive for but hardly any attain - perfection.

The teenager from Onesti in Romania had come to Montreal on the back of dominant performances at the European Championships in Skien. She was confident, but now the competition was greater.

But in the space of 30 seconds she blew her rivals away and raised the roof at the Montreal Forum when her uneven bars routine landed her a perfect 10.00. It was the first awarded to a female gymnast at the Olympics.

Because the mark had never been displayed, the digital scoreboard showed 1.00.

"I think the story was that Longines [scoreboard manufacturers] called the International Gymnastics Federation [FIG] before the Games and asked would somebody be able to score a 10 - the FIG said nobody would score a 10," said Comaneci.

"So when Montreal came, they couldn't accommodate the 10 after the uneven bars routine.

"The 1.00 made history rather than the 10."

She achieved another six 10s and claimed three gold medals that year - a star was born.

Short steps, big feats

Like Fosbury did with his 'Flop' in 1960s, Michael Johnson defied convention.

The Texan ran with little knee-lift, but his leg speed was simply mesmerising. It was a style that few coaches would teach, but it worked for Johnson, with spectacular results.

At the 1996 Atlanta Games - his home Olympics - Johnson had the chance to prove that not only did he have the talent but also the temperament. Could he handle the pressure and the hype?

Johnson had elected to go for the 200m/400m double. The previous year he triumphed in both at the World Championships in Gothenburg - but this was the pressure-cooker of the Olympics.

The first event was the the 400m. He was expected to dominate and he did - winning gold in an Olympic record time of 43.49 seconds.

Next was the 200m. Namibia's Frankie Fredericks had got the better of him in the races leading up to the final, and both he and Trinidad and Tobago rival Ato Boldon were hoping that Johnson would be weary coming into showdown.

"When he stepped up to starting line for 200m final, none of the facts about Fredericks having a winning record in 1996 mattered," Boldon revealed.

"He had to deliver for the sport-loving American public that quite frankly wouldn't have been enthralled with silver. He had to pull off the double.

"The reason why it was amazing was because he had to reach deep inside and do something that he had never done before and never managed to do afterwards."

- Published2 February 2012