Paula Radcliffe's Olympic dream ends in cruel fashion

- Published

- comments

Paula's Olympic heartbreak

"My sport is a beautiful sport. It gives me so much fun and enjoyment. The downside is that it can break your heart and spirit many times over."

Many great champions could provide that precise retrospective. That it is Paula Radcliffe, as she announced her withdrawal from the London Olympics, is a cruel reminder that sport has little interest in neat finishes and valedictions.

Radcliffe was an outside bet for her first Olympic medal in her fifth Games before her degenerative foot condition flared up again in early June.

Her age was not the only issue. Constantina Dita won marathon gold in Beijing, external at 38, the same age Radcliffe is now. The last two Olympic marathons have also both been won in a relatively stately two hours 26 minutes - 11 minutes outside Radcliffe's own extraordinary world record.

The problem was form, fitness and recent runs. While her last marathon, the 2 hours 23 mins 46 secs she ran for third in Berlin last autumn, gave hope of a fairytale flourish this summer in a city where she has never lost over the distance, her only subsequent performance of note was a hugely disappointing 72-minute showing in a Vienna half-marathon in April.

Radcliffe was hampered in Austria by antibiotics she was taking for a persistent bout of bronchitis, something which would have no impact on a race three months later, yet even then she was 12-1 for gold here in London with several bookmakers.

But this was always about more than one final tilt at a place on the podium that had eluded her as a 22-year-old in Atlanta, by a single place in Sydney, to devastating effect in the fierce heat of Athens, external and once again in the smog and humidity of Beijing.

Radcliffe, the greatest female distance runner this country has ever produced, desperately wanted to experience the unique opportunity of running an Olympic marathon in front of her home crowd.

At a point in her career where she could easily have stepped away to enjoy the memories and the company of children Isla and Raphael and husband Gary, she took herself away from them for two months to train at high altitude in Kenya's Rift Valley.

Training for a marathon at her exalted level is brutal stuff, even without the mental pain of re-opening those old Olympic wounds. Radcliffe was willing to do it because the prize was important enough to her.

She had first been diagnosed with osteoarthritis, external in her left foot at the very start of her career. When it returned at the end, necessitating an emergency dash to Munich and sports doctor Hans Müller-Wohlfahrt (who was also treating Usain Bolt), she admits she "cried more tears than ever".

Had the Olympics taken place six weeks ago she would have been on the start-line. Radcliffe, like many great athletes before, has had the particular misfortune of her own best years falling in the middle of the Olympic cycle.

In both 2002 and 2003 she was the world's best female distance runner by a street. One summer brought her the Commonwealth 5,000m title in Manchester and European 10,000m gold amid the puddles of Munich's old Olympiastadion; the next spring, at the London Marathon, she ran the 2:15.25 that still amazes nine years later., external

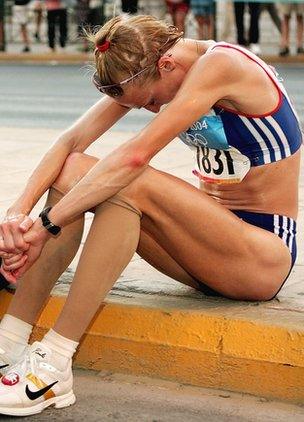

Injury and an adverse reaction to medication ended Radcliffe's Olympic dream in Athens

Neither were Olympic years. A year later, considered as clear a favourite as anyone can be over 26.2 miles of suffering, a combination of freak injury and stomach problems caused by the subsequent anti-inflammatories brought about the infamous collapse four miles from the finish that to the ill-informed remains one of her iconic images.

Sixteen years ago her fifth in the 5,000m final promised much. Four years later she was only denied a 10,000m medal by a last-lap sprint having led for much of the contest. In Beijing a stress fracture of her femur left her short of race fitness. She hobbled home a weary 23rd.

Such timings are in the lap of the Olympian gods. Steve Cram dominated 1500m running in both 1983 and 1985 but struggled with injury in the Olympic year in between and had to settle for silver in Los Angeles.

The man who beat him to gold, Sebastian Coe, had missed the whole of the previous season with toxoplasmosis and would struggle throughout 1985 with back problems. In 1984, Olympic year, he ran clear and free.

Radcliffe's record on the road suggests she deserved an Olympic medal. But, as Mark Cavendish and Michael Phelps could have told you on Sunday evening, the Games pay little attention to reputation.

Radcliffe did win a major championship gold, her marathon triumph at the Worlds in Helsinki in 2005, external going a little way to easing the pain of her Athens defeat the previous summer, but will now end her career without her sport's ultimate prize.

It should not detract from how the nation feels about her.

Her marathon world record, not even approached anyone since, is the sort of Beamonesque mark, external that only a great athlete at an almost unimaginable peak could produce.

Her ceaseless hard work and determination, despite all the setbacks, are a telling example to any young athlete, while her hard-core anti-doping stance throughout her career saw her speak out when many of her contemporaries stayed silent or worse.

There may now be no poetic send-off on the streets she once ruled, but it takes nothing away from the athlete she has been.

"No-one tells us in advance where the limits of our own bodies lie," she said on Sunday. "Pushing these limits is the only way we can ever achieve our highest goals and dreams."

Radcliffe pushed as hard as anyone.

- Published29 July 2012

- Published29 July 2012

- Published25 July 2012