Olympics cycling: Team GB reignite Beijing domination

- Published

The British track cycling team will always have Beijing. For several years it looked as though they had lost their 2008 mojo - but there is no doubt they got it back on Friday.

"Beijing" is more than just the host city of an Olympics they dominated: it is a state of mind, an air of invincibility and a golden sheen that dazzles and intimidates.

For the last four years, the mantra from the Manchester-based squad has been "we will never replicate what was achieved in Laoshan". It is impossible, they said, the rules have changed and the competition has stepped up.

But now, after two days of the London 2012 track cycling programme, it seems Britain's Olympic medal factory might be about to break all productivity records.

Pendleton wins gold in the Keirin

The first four finals in London have brought three gold medals and the team's riders have set six world records.

The only final not to feature a British entry so far came when Victoria Pendleton and Jess Varnish were disqualified for a marginal infringement of a rule nobody quite understands.

The team sprint duo had set a world best on their way to the first ever Olympic final of this event, so it is reasonable to suggest they were in good nick.

Any lingering doubt was dispelled on Friday, when Pendleton produced a staggering burst of acceleration in the final of the women's keirin.

In fourth place with about 400m to go, she surged around the outside to hit the front with 300m left. It was a lead she would not relinquish, and Anna Meares, her great Australian rival, was left trailing far behind.

It has been a bit like that for the entire Australian team in London. They were meant to be the competition who had "stepped up" the highest.

Great Britain's traditional rivals suffered more than most as Team GB won 11 track medals in Beijing, including an unprecedented seven golds.

The one silver they picked up looked very forlorn, so, in true Aussie fashion, they hit back.

The next three World Championships saw Australia top the medal table, peaking in 2011 when the green and gold riders won eight titles.

Having slipped to third in the table in 2009, the Brits were back in second place in Apeldoorn, but trailed Australia by six golds.

A post-Beijing dip was expected for Britain's riders - some of the class of 2008 had retired, or moved on to new challenges - but with a home Olympics now just a year away there were some serious questions to be asked at British Cycling HQ, particularly as the team received £26m in public funding.

Could it be possible, for instance, that the team's performance director Dave Brailsford had got a bit distracted by his Team Sky side project?

This was the crusade he had launched in 2010 to produce a British winner of the Tour de France by 2014. Some said it was worthy, others crazy.

Or perhaps certain riders were being allowed a London swansong, when a more focused operation would have already given them a carriage clock and waved them out the door?

This was not an easy time. Coaches came and went. Experimental line-ups were tried and jettisoned. And real lives sometimes got in the way.

But there was no panic. Brailsford's contribution to the team's success in Athens, Sydney and Beijing bought him some breathing space. Trust me, he told his inquisitors, and trust our athletes.

He was right, of course.

The first signs of the recovery came in February at the London Velodrome's test event, a World Cup competition that attracted most of the world's best riders.

Concentrating on events that would be on the Olympic schedule, Britain picked up seven medals, including four golds - a reminder to anybody who had forgotten Beijing.

GB win pursuit in world record time

That message would be underlined two months later at the World Championships in Melbourne.

Just looking at the 10 Olympic events, Britain claimed eight medals, including five golds. The hosts could only manage three wins in those events, and for the first time since August 2008, they were looking up at Britain in the medal table again.

But even at this point, you would be hard pushed to find anybody connected to British Cycling ready to start talking along Beijing lines.

There was good reason for this: the sport's international governing body had not enjoyed the sight of one nation riding off with all the accolades last time, so scrapped the individual pursuit. In 2008, Britain won gold and bronze in the men's and gold and silver in the women's.

They also made it one rider per nation in each event. There would be no all-British clashes in London finals.

They used to call this kind of thing Tiger-proofing in golf., external

The International Cycling Union is unlikely to advocate stretching velodromes to level the playing field, not with Bradley Wiggins, so it will be interesting to see what it comes up with for Rio.

Wiggins, as it happens, was at the velodrome on Friday to cheer on Pendleton and the four men trying to defend the Olympic team pursuit title that he had helped win in Beijing., external

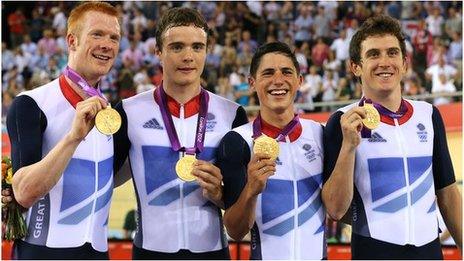

They were up against Australia in their final too. Like Pendleton, they destroyed them, breaking the world record they had set in qualifying on Thursday to give Britain the first back-to-back Olympic team pursuit success since the Germans managed it in the 1970s.

Theirs was a performance of unparalleled precision, and Wiggins, Kobe Bryant, George Osborne, Tony Blair, Stella McCartney, yours truly and nearly 6,000 others can say we were there to witness it.

As a bonus, we also got to see Britain's women's team pursuit trio set a world record in their qualifying round.

So that Beijing vibe is definitely in the air. You can sense it and you know the other nations can sense it too.

As Australian team pursuiter Jack Bobridge said: "You can't take anything away from a team that beats you riding times like that. Massive congratulations to the British."

There are six more medals to fight for over the next four nights and this is a ticket that will only get hotter.

- Published4 August 2012

- Published3 August 2012

- Published3 August 2012

- Published3 August 2012

- Published2 August 2012