Ennis, Farah and Rutherford give GB athletics its finest hour

- Published

- comments

Great Britain's golden Saturday

There was a point in the Olympic Stadium on Saturday evening, at about 9.20pm, when you wanted to put the world on pause and just revel in it all for a moment before the next wonderful thing caught you round the chops.

One day, six Olympic gold medals for Great Britain? Hell, in one hour, around one small oval of track in east London, British athletes won three golds in such dizzying, dreamlike succession that all context and precedent disappeared off into the dark London sky.

You tried to grab a record book before they all got thrown on the bonfires. In the 16 Olympics from 1928 to 1996, only once did Britain win more than five golds in an entire Games. Not since 1908 had GB won five in a day, and that was an event so unrecognisable it included tug-of-war and real tennis.

The greatest single hour, the best night, unarguably, in the long history of British athletics. The best day in British sport? It sounds like hyperbole, so apply what logic you have left.

Saturday's medal count, taken just on its own, would constitute Great Britain's ninth most successful Olympic Games tally in 118 years of competition.

In three different sports, by men and women, on water and on dry land, the golds kept on rolling in, roared on by partisan crowds at stadiums across the city and its hinterland and by millions on television, radio and electronica.

From Eton Dorney to the velodrome at the north end of Stratford's Olympic Park to within toasty distance of the Olympic flame itself, there was the same expression on British faces: I can't believe I'm here, I can't believe I'm watching this.

What do you have to compare it to? England's World Cup win in 1966 was precisely that - England's. So was Jonny Wilkinson's iconic drop-goal, external in Sydney nine years ago.

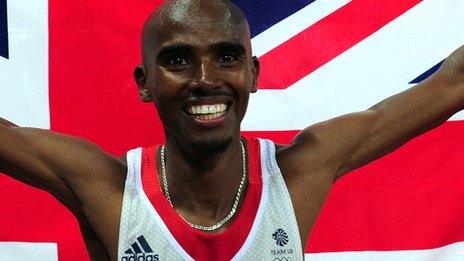

BBC Olympics experts go crazy for Mo Farah

This one truly belonged to Britain - a collective grin of national pleasure, a domino-chain of sporting success that had you clapping and cheering new heroes like you'd loved them all their lives.

The rowers had started the celebrations with gold in the men's four and the women's lightweight double sculls before track cycling's women team pursuiters added track cycling gold.

That was quite good enough. But those lucky enough to be among the 80,000 at the athletics were about to hit the jackpot in quite unprecedented fashion.

We knew after the morning's long jump and javelin that Jess Ennis would, barring pestilence and plagues of locusts, be crowned Olympic heptathlon champion. We hoped that Mo Farah might do what no British male had ever done and win a global 10,000m title. A few even lumped some cash on Greg Rutherford to win the long jump, although a gamble was exactly how it felt.

That all three came off in 46 minutes left you laughing with disbelief at the madness of it all.

When London hosted the Games for the second time in 1948, Britain failed to win a single track and field title. Having waited 104 years for an athletics gold, three arrived in the city in such quick succession that the waves of noise barely stopped rolling.

When you looked up at one point and saw the women's 100m was about to start, there was genuine surprise. When a race so good the sixth place athlete runs 10.94 seconds feels something of an anti-climax, you know you've witnessed something altogether rare.

Seven long years ago, when the 2012 Games were awarded to Britain, athletics in the host country could not have been at a lower ebb.

The British team returned from that summer's World Championships in Helsinki with a sorry haul of one gold and two bronze, ending up buried down at 16th in the medal table behind such track and field powerhouses as Estonia, Bahrain and Belarus.

To have predicted then the sort of giddy scenes we witnessed in London on Saturday night would have been to invite scorn and straitjackets.

That it happened to Ennis, Rutherford and Farah had a neat symmetry and happy resonance.

Four years ago in Beijing, all three were enduring the sort of miserable sporting slump that makes you want to sack it off and do something less capricious instead: Rutherford, nowhere and unnoticed in 10th; Farah, gone in the heats; Ennis, watching it all at home in Sheffield with her fractured right foot encased in plaster.

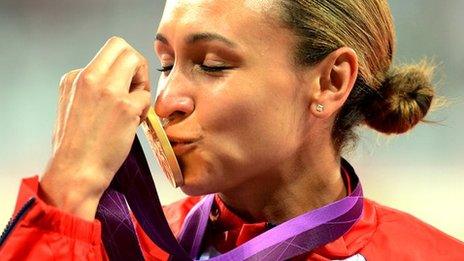

Tears of joy for gold medal winner Ennis

Here, enveloped in an atmosphere they could barely have dreamt of then and will never experience again, they touched the heights.

The Sydney Olympics of 2000 famously proclaimed it Magic Monday the day Cathy Freeman won 400m gold. London's Super Saturday had three Freemans in the time it takes you to walk across Olympic Park.

All three, wrapped in Union flags, spoke eloquently if bemusedly about what they had just experienced.

"I told myself at the start," said Ennis, "that I'm only going to have one moment to do this in front of a crowd in London. I just wanted to give them a good show."

"This is what I have dreamed of my whole life," said Rutherford. "To do it in London is just incredible. I might wake up in a minute."

Farah's blistering final lap was the crescendo to it all. As he crossed the finish line, Olympic great Kenenisa Bekele in his wake, his wife Tania and step-daughter Rihanna ran on to meet him.

Tania is eight and a half months pregnant with the couple's twins. Not now, you thought - please not now.

Eight days ago, Danny Boyle's opening ceremony offered a vision of modern Britain that felt simultaneously new and familiar to every one of us.

These athletes are making it flesh, just as the experience of watching them is giving the nation a series of mutual memories to celebrate and cherish.

A mixed-race girl from Sheffield, a lad whose great-grandfather played football for England over a century ago, and a boy who arrived in west London aged eight from east Africa to make the capital his home.

"Would you have been prouder to have done it for Somalia?" some clown asked Farah at his media conference. The rabid Arsenal fan was indignant. "Not at all, mate! This is my country!"

The old sages always agree on two things: a Games needs a home medal in its main stadium to truly come alive, and it needs a definitive night for everyone to remember it by.

As you looked around the Olympic Stadium on Saturday night, Paul McCartney conducting the crowd from his seat as they sang, "All You Need Is Love", just as he had the velodrome to "Hey Jude" a few hours before, you realised: this is it.

This is the moment. This is the definitive night, and day, and hour.

- Published4 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012

- Published5 August 2012

- Published5 August 2012