Bach orchestrating change as Olympic’s great reformer

- Published

Thomas Bach: "The fact is that the world has changed ands we need to reflect that in the bidding process"

A sense of calm surrounds Lausanne, a peaceful Swiss town where change tends to happen very slowly.

But at the International Olympic Committee's headquarters here on the serene banks of Lake Geneva, revolution is in the pristine air.

IOC President Thomas Bach is a man on a mission. Last year I interviewed him in Buenos Aires, just hours after he had been elected as the most powerful figure in world sport.

Ever since then, the German has been devising the raft of reforms that he believes the Olympic movement must implement to protect one of the world's most enduring and powerful brands, and to change with the times.

And now, as we meet again at the home of the Olympic movement, he tells me he is finally ready for the revamp.

Agenda 2020 is a reboot designed to make the Games friendlier, more flexible, and above all, affordable.

Next week in Monaco the IOC will meet to vote on the 40 proposals, including the launch of a global digital Olympic TV channel, and the target of more sports, but less disciplines.

"It's very important" he tells me, "We've been in talks now for a year. But we're about to go from discussion to decision and it's time. I'm really looking forward to finally getting there.

"It's about an IOC that is safeguarding the uniqueness of the Olympic Games, safeguarding the Olympic values, and an IOC which is progressing youth and strengthening sport in society."

Image problem

After the success of London 2012, the growing list of sports desperate to be part of the Olympic programme, and the continued popularity of the product - NBC have paid almost $8bn for the broadcast rights to the next six Games - some may be surprised that Bach feels the need for change. After all the 2024 Games are expected to be keenly contested.

Thomas Bach was elected IOC president in September 2013

But the IOC has an image problem too. The winter Games in particular have begun to resemble something of a luxury.

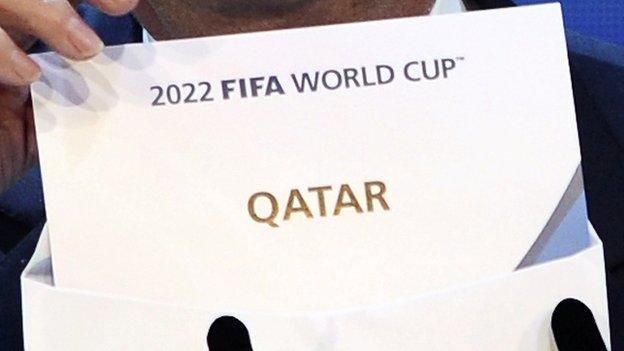

After a humiliating bidding process, the 2022 Games are the subject of just a two-horse race between Beijing and Almaty in China and Kazakhstan respectively, neither of which have human rights records to write home about.

Four other cities (in countries with democratically-elected governments), including favourite Oslo, all pulled out after lukewarm public support and political opposition due to the perceived cost of bidding.

The IOC were criticised when a long list of so-called 'demands' was revealed, painting a picture of arrogance and largesse that Bach insists is unfair.

"The so-called 'demands' were not demands," he insists. "They were examples that we made available in our 'transfer of knowledge programme' to future organisers, just advising the bidding cities."

But Bach is all too aware that after the reported $50bn cost of the Sochi Games, the most expensive sports event in history,

Western states appear to have been scared off. The traditional assumption that hosting Games is an investment that pays off in the long-term is under threat.

Work to be done

Bach is determined to persuade potential bidders that they need not worry, and urges the critics not to confuse the actual operational budget of staging a Games with the much greater infrastructure expenditure that countries like Russia have chosen to embark on.

"There is great work to be done there because the perception is wrong in many parts of the world," he admits.

"We have to explain and communicate about the cost of the games.

"The cost of the winter games have been stable over the last few editions and the operational budget is profitable - we have to explain that you cannot take the cost of housing construction of an Olympic village as the cost of the games."

Critics will argue that the two areas of expenditure go hand in hand and to separate them is rather convenient for the IOC, but Bach believes the organisation deserves more credit for its financial contributions to host cities.

In the case of Rio 2016, $1.5bn. Oslo would have received $880m. The IOC will not pay more, but does want to slash the cost of hosting by encouraging cities to use existing facilities.

"Where we have to change is the overall concept of bidding," he tells me.

"In the past we were approaching potential candidate cities in a way a little bit like a tender for a franchise. We would say 'if you want to organise Olympic Games you have to have one stadium with this capacity, three more with this capacity', and so on.

"And there we have to take a different approach. Rather than putting conditions in this way, and telling cities how they should organise games, it is much better to to ask cities how they think the games would fit best into their sporting, social, financial and ecological environment."

Hence Bach's proposals to encourage future hosts to suggest sharing costs by staging events in neighbouring cities or even countries, to be open to regional Games and to push for sports that are popular with the young in a particular host country.

"We have to be more flexible," he says.

"The system worked will in the past - you saw a sport develop slowly, then there would be championships.

"But in today's world it's totally different - today sport appears becomes popular whether it's governed by a fed or club doesn't matter so much so we have to look into these sports and events and see what is really inspiring youth to watch and play sports."

He may be the ringmaster of the greatest show on earth.

But In this age of austerity, Bach is all too aware that nothing can be taken for granted.

The Olympics' great reformer is about to make his mark.

- Published1 December 2014

- Published5 November 2014

- Published2 October 2014

- Published30 November 2014