Rio Olympics 2016: Mo Farah, Jessica Ennis-Hill & Greg Rutherford's special day

- Published

- comments

Gold for Mo Farah, silver for Jessica Ennis-Hill, bronze for Greg Rutherford. It might not have been Super Saturday II, but this night of twisting plotlines was many other things besides - Stressful Saturday, Seesaw Saturday, So Close Saturday.

At one point it was Sugar He's Fallen Over Saturday. By the end, the world's best heptathletes were strung out legless and exhausted around the track like a broken necklace of pearls. It was simply special.

Farah, winning his eighth successive global distance title, joined that most select band of men to retain a 10,000m Olympic title, the first British athlete to win three Olympic golds.

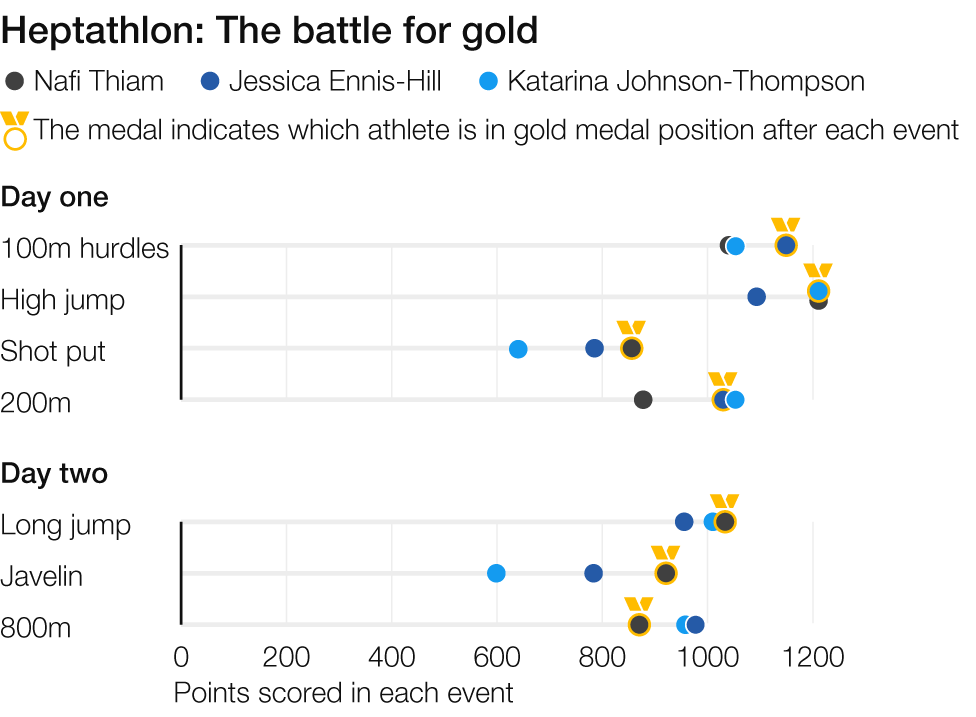

Ennis-Hill, on her knees after falling just a couple of seconds short, celebrated all the same behind a brilliant 21-year-old who had set personal bests in five of her seven events, for how do you beat a woman who keeps beating herself?

Rutherford, a driving force in one of the great long jump finals - in terms of drama if not distance - produced at the death a jump just two centimetres down on the one that won his gold in London, only 10 centimetres away from another.

There were tears from all three, and only the cruel or careless could not fathom why.

That night in London four summers ago brought its own emotional weight and expectation. What united a nation across 46 magical minutes in Stratford has both defined this special trio and hung over them in the hard days and long nights since.

Not since the 10,000m at the World Championships in Daegu five years ago has Farah been behind on the final lap of a global championship. Never before has he been sent tumbling to the ground mid-race, as he was here after tangling feet with training partner Galen Rupp.

Not once across all those golden runs - two at London 2012, two at the 2013 Worlds in Moscow, two more at the 2015 Worlds in Beijing - has he ever been pushed so hard.

In the warm Rio night air afterwards there were none of the usual smiles. Instead, he looked both stunned and shattered, the sense of how close fate had come to detonating his dreams haunting him even as the Union flags fluttered all around.

"You can't imagine how hard you work for it, and in one moment it could have gone," he said, wide-eyed and wet-cheeked.

Mo Farah fell to his knees after retaining his title

"Once you've fallen, it's hard to get back up and win. I was thinking 'No, no, I can't let Rhianna [his stepdaughter] down'. I always wanted to do it for her. My twins got the double gold from London and I promised this one to her. That's what drove me home."

Ennis-Hill, who at this point two years ago was giving birth to her son Reggie and who has invented a new statistic to measure her sometimes unlikely and often remarkable return (PPPB, or post-pregnancy personal best), left the Estadio Olimpico several hours past midnight, a new dawn in the distance at the end of two long days.

This may the last time we see this relentless competitor on the track or runway, the attrition of her chosen sport and the attraction of growing the family with husband Andy finally winning out after a career where she has delighted in upsetting precedent and prediction.

Ennis was supposed to be too small to succeed in heptathlon, a sport dominated by those with long levers to throw and jump. Eight years ago a stress fracture cost her the chance of going to her first Olympics at Beijing 2008. She has had to compete against women once banned for doping and others who were only retrospectively sanctioned.

None of it has stopped her. Part of a singular odd couple with coach Toni Minichiello, she first won one world title and then took back that crown back as the mother of a young child, her triumph in London one of the iconic moments of an impossible fortnight.

In Nafi Thiam, the future has invaded the present and rosy past. The young Belgian heptathlete's margin of victory may have been just 35 points, the equivalent of two and a half seconds in the epic 800m showdown that sealed her win, but a chasm could be about to open up.

Thiam smashed her former overall PB by 302 points, and she is still a student at university. This is now her event to own and redefine, and Ennis-Hill, even at 30, seemed to sense that one age may be over.

Then there is Rutherford - world champion, Commonwealth champion, twice European champion, but not satisfied with any of that, not willing to cede the biggest prize of all even to men with longer personal bests, with rivals demonstrably in better form.

Saturday night was classic Rutherford, taking an early lead in the first round, refusing to be shaken by the sight of three of his competitors each overhauling him, nearly regaining the lead with a marginal foul later ruled as good, finding his biggest leap of all in his final round to drag himself back on to a podium he topped with such elan four years ago.

It was classic Rutherford in his reaction too. "I'm gutted," he said, "I come into these competitions to win."

Pain came not only from the loss of his title but for the sacrifices made in its pursuit. Rutherford feels strongly his enforced absence when training from 22-month-old son Milo and felt regret for those gathered at his house in Woburn, burning the late-night oil to support him from afar.

Like athletics as a whole, he may come to look back on these few hours with satisfaction rather than dismay.

In a horrible era for the sport, its governing body shown to have been laced with corruption, its former kingpins in disgrace and its great medal-winning powerhouse Russia banned from competition for state-sponsored doping on a geopolitical scale, this was a reminder of how good it can even now sometimes still be.

In just over an hour between 9.10pm local time and 10.20, the narrative drove at a breathless pace.

Medal table | Gold | Silver | Bronze | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. US | 24 | 18 | 18 | 60 |

2. China | 13 | 11 | 17 | 41 |

3. Great Britain | 10 | 13 | 7 | 30 |

4. Germany | 8 | 5 | 3 | 16 |

Three centimetres covered the first three long jump places, while 50 metres away Ennis-Hill was throwing what looked to be a title-winning 45.91m in the javelin. Farah was jogging to the start line two minutes before Thiam threw a stunning 53.13m.

The gun was going for the distance runners as Rutherford went into the lead. Ennis-Hill was waiting for Farah to pass before going again. Farah was falling and scrambling to his feet as Rutherford watched South Africa's Luvo Manyonga soar into the lead himself.

And so it went on, a riot of unrelated yet intrinsically linked athleticism, a broad stage running concurrent and complementary shows. Lean men, powerful women. Speed merchants, endurance kings. Europeans, Americans, East Africans, Australasians.

At the heart of it all, Britain's contrasting triptych: the immigrant kid who arrived in west London aged eight to make the capital his home, the middle-class boy whose great-grandfather played football for England over a century ago, the girl from Sheffield who won against the odds and won again as a mother.

Of course there could be no sequel. Alone they have been outstanding. Together they have been unique.

- Published14 August 2016

- Published14 August 2016

- Published14 August 2016

- Published14 August 2016

- Published18 August 2016

- Published3 August 2016

- Published19 July 2016

- Published3 August 2016