Rio Olympics 2016: The inside story of the Brownlees' triumph

- Published

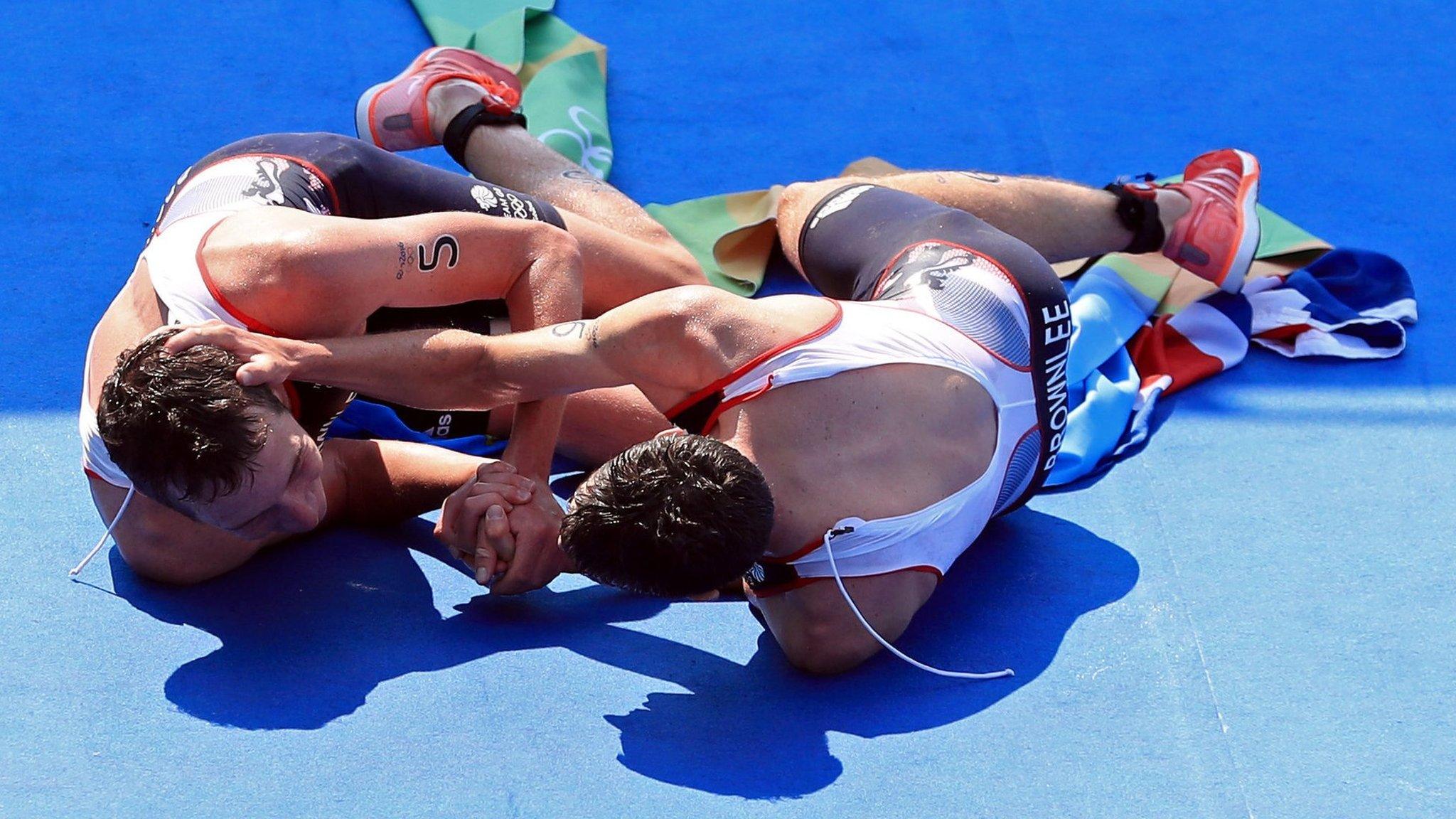

Four years ago in London a gold and bronze, on a scorching Thursday around Copacabana's streets and blue waters the gold and silver.

To outsiders, the second chapter of the Brownlee brothers' triathlon triumph might seem somehow preordained, the two tough lads from Yorkshire doing what they always do. Alistair becomes the first triathlete, male or female, to retain an Olympic title. Jonny follows him home, the only one to get close to the greatest one-day racer in the world, the only one able to push him to his limits.

Yet there are no guarantees in elite sport, no free rides nor effortless medals.

This may have been the prettiest triathlon of all: a cloudless sky, the blue carpet laid over soft sand, Sugarloaf Mountain one way, palm trees and soft surf the other.

It was also a brutal course, in weather hot enough to make those watching wilt, set too against a backdrop of injury, uncertainty and defeat.

This is the inside story of a happy ending to a remarkable tale.

Rio Olympics 2016: Brownlee brothers on finish line moment

The doubts

The brothers jogged to the start line looking as stressed as the kite-surfers who had been out on the bay at dawn: smiling, shaking out legs, waving at friends and union jacks on the crowded surrounds.

Calm on surface, strong currents underneath.

Since that golden afternoon in London in 2012, the Brownlee hegemony that seemed set to last for years has been broken by both inspired rivals and the collateral damage of their punishing training regimes.

In the three years since, the World Series title has gone to their Spanish rival Javier Gomez each time. Jonny has suffered a stress fracture that cost him the 2015 season; Alistair's problems with his Achilles and ankle left him wondering if he could ever get back to the peak that saw him crowned world champion at 21 and Olympic champion at 24.

This season alone, with Gomez struggling himself and then ruled out of Rio with a broken elbow, the World Series has been dominated by his younger compatriot Mario Mola, a third Spaniard, Fernando Alarza, also a growing threat.

It has required a recalibration of the way the brothers train. After a successful operation on that troublesome ankle late last year, Alistair had to cut back on the red-line sessions - the ferocious self-immolations that have both given him his edge and sometimes pushed his body too far.

A drop in volume, a renewed focus on recovery and rehab.

Both have had to let the early season races slip by either without challenge or in defeat. For this was a season where only one race really mattered. And what mattered even more was being on Copacabana beach on Thursday both fit and at a fresh peak.

Alistair Brownlee wins triathlon gold

The desire

Triathlon offers its greats only moderate financial reward. Its training load - three sessions a day, in the pool to swim 4,000 metres of drills and intervals before breakfast, riding hills and headwinds through the morning, running again on the footpaths around Bramhope or the playing fields of Leeds Beckett in the early evening - is enough to give some professional sportsmen nightmares and others stress fractures.

It cannot be done without a great love for both the daily grind and an ability to soak it up. No corners cut, no quarter given.

In a defining race like this all that at last makes sense, for without having gone through it in training, there can be no getting through the immense physical privations that broke so many others along the Rio waterfront.

"It would seem quite strange to a lot of people, that you could actually enjoy physically hurting yourself. It doesn't seem to make sense," Alistair has said. "But I can.

"I actually love this. I thrive off pushing myself, not only if it's a competitive situation, trying to hang on to someone, but also just on my own, being able to push myself and hurt.

"I've got no idea where that's come from. Although I think my dad would tell you, even the first time he saw me doing cross country as a six-year-old, I went red in the face and looked like I was about to die. So maybe I had it even then."

Alistair Brownlee (right) retained his Olympic men's triathlon title to win Britain's 20th gold medal of the Rio Games, with brother Jonny claiming the silver

The background

This was a victory won on sun-baked Brazilian streets but forged on the damp roads and dark mornings of a childhood in Leeds.

Riding came naturally: the Yorkshire Dales fan out in an inviting green arc from the Brownlees' home town of Horsforth. So too did hard running. The fells above Haworth and Burnsall toughened legs, the interval sessions with Bingley Harriers tested hearts and minds.

Swimming came via the local pool at Aireborough and then a singular coach with the unforgettable name Coz Tantrum. Bikes and tri-suits came from Triangle Bikes, one of the first specialist triathlon shops in the country, that also happened to be just a few miles down the hill from the family home.

Cycling routes came from the shop rides owner Adam Nevins used to organise; running opportunities came from an inspired teacher at Bradford Grammar, Tony Kingham, who would let his cross-country team leave the school gates at lunchtimes to run wherever they liked.

Serendipity to some, an open invitation to two boys who only wanted to swim, to bike, to run. And to challenge themselves whenever they could.

There is even a grandfather, in former merchant navy sailor Norman, who puts the boys' swimming genes down to the fact that when his ship was sunk during the Second World War, he was capable of swimming to shore.

The Fabulous Brownlee boys |

|---|

Both born in West Yorkshire |

Both educated at Bradford Grammar, both still live in West Yorkshire |

Alistair is the Olympic, European and Commonwealth champion |

Alistair is the first man to retain the Olympic triathlon title |

Jonny won bronze in London 2012 and silver in 2016 |

The bond

The sibling rivalry can be hard for the two brothers. In the months leading up to London, both living in the same house, it sometimes became too much.

Jonny is the organised one, Alistair the laissez-faire. Jonny packs his kit bag the day before races, Alistair a few minutes before he leaves.

The younger brother is comfortable being part of a team; Alistair, iconoclastic, has all the instinctive self-doubt of Brian Clough. Each can annoy each other the way only family members can.

You might think that coming up against your biggest rival in every session on every day would be disheartening, or wear you down, or leave you fearful of what you see they are capable of.

Instead the brothers use it as the most perfect motivation tool possible. Never an excuse for taking it easy. Never a doubt about what it will take to come out on top.

In a World Series race, external it gives each a team-mate they can trust like no other. In the unmatched pressure of an Olympic final it is both an arm round the shoulder and a rocket up the backside.

On a course like Rio's, when the most advantageous tactic was to hit it hard in the early part of the steep bike course to open up a gap over the strong runners and take the legs out of those who could stick with them, the partnership was at its most valuable and dangerous.

Together the brothers drove the lead group on, leaving Mola adrift in the second group, shouting at those alongside them to pull their turns on the front. Sibling symbiosis, and no-one outside the family could do anything to break it.

The Brownlees dive into the sea at the start of the Olympic triathlon

The practice

This was a course with much more jeopardy than the picturesque yet tame parcours around Hyde Park four years ago, a race with more opportunities to escape rivals yet more danger around its tight turns and steep ramps.

Neither was there the familiarity of the same hotel where they have stayed many times before, nor security manned by British troops who that early morning in August waved the Brownlees through without a second glance before forcing their foreign rivals to open up every bag they carried.

But there can never again be the same pressure as a home Olympics, never quite again the same expectation that comes from having home support stacked 12-deep around the barriers and hanging out of the trees beyond.

These are two racers, at 28 and 26, who know what to expect on the biggest stage of all and understand how to handle it.

As they did in London, they have stayed away from the athletes' village in Rio, preferring to stay in a quiet hotel in Ipanema, one bay round from the scene of their great test.

They have prepared, as before, with a training camp in St Moritz, on climbs they are familiar with, at an altitude that has pushed them in the past. They have coaches, in Malcolm Brown and Jack Maitland, who they have trusted for years, and a physio in Emma Deakin who knows the idiosyncrasies of their contrasting physiques.

When they stood on the sandy beach of Copacabana, goggles down, hats pulled low, there was nothing left to shock or unsettle.

"I've stood on thousands of start lines, and it's a slow progression from the start line of a Leeds school cross country race to the Olympic Games," says Alistair.

"But I wanted to win the Yorkshire Cross Country Championships when I was 12 just as much as I wanted to win the Olympics when I was 24."

Fresh faced as a member of the 2008 GB Olympic triathlon team - but always with a huge desire to succeed

The perfection

When the nine-year-old Alistair entered the Leeds Schools cross-country championships, he finished 400th of 450 entrants.

In the 19 years since he has gradually metamorphosed from callow, red-cheeked kid into the greatest male triathlete there has ever been.

There is so much that is ordinary about the Brownlee brothers. Breakfast at Alistair's is large bowls of own-brand discount supermarket cereal. Jonny's favourite tea is fish and chips, eaten Yorkshire style with a side-plate of white bread.

Jonny likes to relax by watching Leeds United at Elland Road or Leeds Rhinos at Headingley. Alistair, sufferer supreme in his sport, likes to watch rom-coms. When he went out to buy a new car, he promised to buy an Aston Martin and came back with a Volvo.

They are also unmatched across one of the most testing Olympic events of all. Rio was all that has led up to this race, but also their racing in microcosm: relishing the challenge, rising to its demands; appreciating the tactics, having the legs and heart to see them succeed.

- Published19 August 2016

- Published18 August 2016

- Published21 August 2016

- Published18 August 2016

- Published3 August 2016

- Published19 July 2016

- Published3 August 2016