Tokyo Olympics: Karsten Warholm world record evokes Bolt and Beamon on magic day

- Published

Tokyo Olympics: Karsten Warholm sets incredible new world record in 400m hurdles

Tokyo Olympic Games on the BBC |

|---|

Dates: 23 July-8 August Time in Tokyo: BST +8 |

Coverage: Watch live on BBC TV, BBC iPlayer, BBC Red Button and online; Listen on BBC Radio 5 Live, Sports Extra and Sounds; live text and video clips on BBC Sport website and app. |

Numbers shouldn't clash. A combination of digits shouldn't look strange.

'Red and green, never seen' they say. They never warn you that one Tuesday afternoon in Tokyo, four and five will make you check you're still alive.

That was the sight that greeted Karsten Warholm as he crossed the line in the 400m hurdles final.

The Norwegian came into the race as the world record holder. Five weeks ago he took eight hundredths off one of track's longest-standing marks, lowering Kevin Young's 29-year-old record to 46.70 seconds.

On that occasion, he sunk his face into his hands. This time he didn't dare.

Warholm, eyes shocked wide, kept glancing back at the clock, fearing there was an error, that the time would be revised, that he was still asleep in his cardboard bed back in the athletes' village.

But it stayed and stood.

45.94.

The figures so stark and shocking, they almost needed to be written out in full, in words, in brackets, vidiprinter-style, to be believed.

A whole three quarters of a second faster than any man had run the distance.

"Times you can only imagine, only dream of," shouted commentator Steve Cram as Warholm ripped apart his vest in celebration.

Because some numbers not only resound around the globe, they echo in history too.

Most world records are marginal gains. The hard-won erosion of a few centimetres, a handful of hundredths. Years of training rewarded with a pipette's worth of improvement.

Others are of an altogether greater magnitude, so far off the scale they seem to come from another cosmos entirely.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

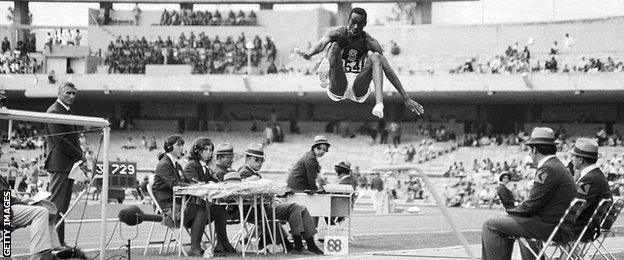

Heading into the 1968 Olympics, the men's long jump record had been advanced by 3cm, 2cm, 1cm and 1cm over the previous few years.

Beamon's world record at Mexico 1968 required an old-fashioned tape measure as it exceeded the range of the optical measuring device

Then Bob Beamon soared through the thin Mexico air, beyond the range of the electronic measuring device and out to an unheard-of 8.90m, another 55cm further.

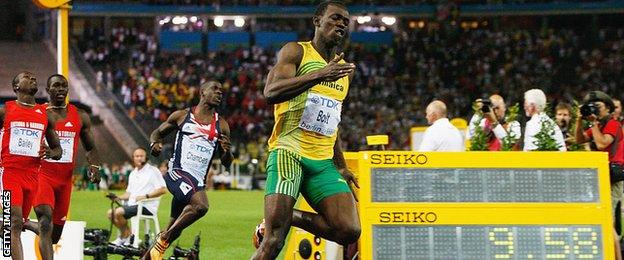

In Berlin in 2009, Usain Bolt put the 100m world record out of reach of a generation, if not the rest of humanity, with a gasp-inducing 9.58 seconds.

At Atlanta 1996, Michael Johnson lopped an astonishing third of a second off the 200m mark.

Ato Bolden, back in third, summed up the incomprehensible sight.

"19.32!" he exclaimed. "That's not a time, it sounds like my dad's birthday."

Warholm has made a similarly quantum leap in the possible and credible.

His time was so unmoored from expectation and precedent, that in the immediate aftermath you had to go hunting for context.

You looked at his competition, and saw American Rai Benjamin a good couple of metres behind Warholm, but still half a second inside the old world record.

You looked at the points tables, World Athletics' guide to comparing performances across events, and saw it equated to a three-minute-39-second mile.

You looked at the percentage improvement on the old world record - 1.6% - and imagined if 100m gold medallist Elaine Thompson-Herah had run 10.32 seconds, rather than merely 10.61, on Saturday night.

Whatever angle you took, it looked other-worldy and weird. And for some, there was good reason.

The technology on and under athletes' feet has shifted.

Warholm's spikes may not contain the resilient, responsive foam of others, but they are stiffened by a carbon plate that returns energy lost to older generations.

Bolt's 100m world record was set 12 years ago in Berlin and is unlikely to be overhauled soon

The Mondo track surface, tweaked and tuned for Tokyo, seems softer, bouncier, quicker than ever.

For some, together, they distort historical comparisons beyond recognition.

For them, we are entering an era akin to the one, a little over a decade ago, where the skin suit overshadowed swimming.

Back then, full-length Nasa spacewear shredded record books to tickertape before the sport's governing body banned them and belatedly bolted the stable door.

World Athletics have ruled on shoes. In January 2020, it set limits on sole depths and the number of carbon plates, rather than banning either innovation outright.

Then then postponement of Tokyo 2020 allowed rivals to close the gap on pioneers Nike, levelling the playing field to a degree.

It will take time to see if it is a true watershed. Whether historical trends have really been thrown into flux.

But Warholm is a generational talent who shines through the fog of technology wars.

His performance was one of shock and awe to rival Bolt or Beamon, regardless of the quibbles.

And his time, whatever caveats your brain might demand, sent a visceral thrill though the spine, Tokyo, Japan and beyond.

'In my eyes, anyone can be an influencer': Is social media a viable full-time career at 16?