'Rugby league gave me brain damage' - ex-Australia international Ian Roberts

- Published

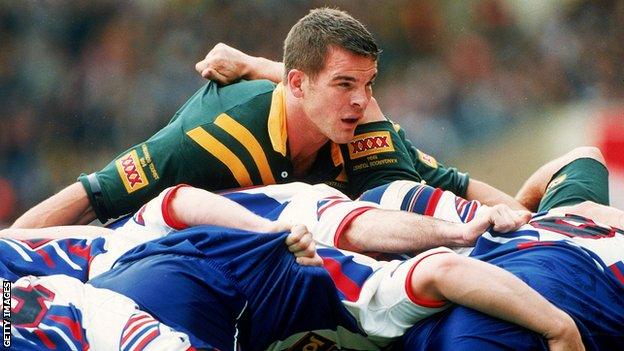

Roberts won 13 caps for Australia between 1990 and 1994

"To be told you have brain damage is really hard to hear," says former Australia international Ian Roberts.

"I was fully aware there was something wrong with me, but to be told I had scarring on the brain was surprising. It's irreversible damage."

Roberts, 52, is one of 25 retired National Rugby League (NRL) players who took part in a study into the effects of repeated concussions on the brain.

The study, published on Thursday, found repeated head injuries suffered during the players' careers had left them with long-term impairments.

The NRL said it was "aware of the study" and added it "takes concussion seriously and is continuing to adopt international best practice in concussion management".

Roberts said: "Players need to be aware so they can make their own, informed decision.

"They need to know the consequences of repetitive concussions, because there's a price to pay."

Last year, Super League players Luke Robinson and Kevin Brown expressed fears over their futures after repeated concussions during their careers.

Former Huddersfield scrum-half Robinson, who retired in 2016, says he was knocked out at least 30 times playing rugby league.

Both he and Brown said the game was getting to grips with head injury protocol, making it much safer for players now beginning their careers.

'I was struggling to learn my lines'

Roberts won 13 caps for Australia during a 12-year playing career - which included a stint in England at Wigan - and is no stranger to confronting a taboo issue.

In 1995, then aged 30, he became the first high-profile rugby league player to publicly reveal he was gay.

After retiring from the sport in 1998, the front rower began an acting career - something he says has been affected by his brain damage.

"I've had some complications with my mental health since retiring from rugby league," he told BBC Sport.

"My first major concussion was in my early teens, and when I turned professional I was knocked unconscious on 14 separate occasions.

"In the last five years I've noticed my recollection of things has slowed down and my memory isn't as sharp as it was. I first realised it at rehearsals for plays because my ability to learn lines has deteriorated. I'm just not as sharp as I was in the past."

How did the study work?

Roberts says he agreed to take part in the study to find out if his symptoms were a direct result of playing rugby league.

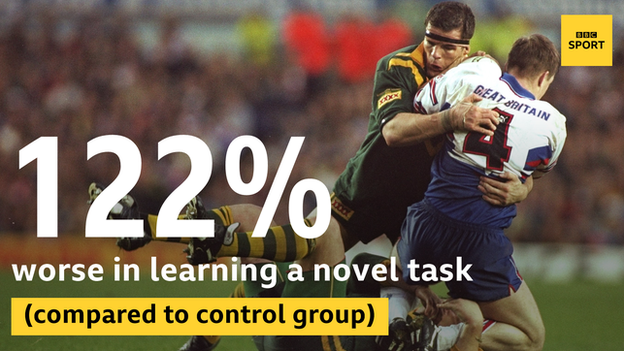

The research, conducted by concussion expert Dr Alan Pearce, studied 25 former NRL players and compared them with 25 men of a similar age with no history of concussion or brain injury.

Aged between 40 and 65, the men completed five tasks relating to memory, short-term learning and attention, reaction time and fine motor skills.

"The objective of the study was to look at how the players have fared 20 years after their last concussion in a competitive rugby game," Pearce said.

"When we compared them to the healthy group, who were matched for educational level, there were a number of differences.

"I would have expected the players to outperform the control in the learning of a novel task due to the way they have trained as athletes, but they really struggled in learning new material."

Test carried out | Differences between NRL players and control group |

|---|---|

Picking up, manipulating and placing three small pins into different holes | 20% worse in fine motor skills testing |

Response to touching a target when it appears on a tablet screen | 15% slower in reaction time |

Identifying the location of discrete patterns concealed behind boxes on a screen | 122% worse in learning a novel task |

Repeatedly finding and remembering tokens located behind boxes | 98% worse in working memory |

Concentrating on one figure as two figures are randomly displayed on a screen | 71% worse in maintaining concentration |

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | 76% returned abnormal brain responses |

'We need to be optimistic'

Pearce and Roberts share the same outlook on the outcome of the testing - they are optimistic.

"This shouldn't be seen as a death sentence," Pearce said.

"We now know people can improve their brain function through cognitive training, learning new skills and exercise.

"I don't know whether we can stop the decline completely, but at least if we can slow it, then we can provide a number of years of good quality of life."

Roberts has been doing brain rehabilitation - in the form of cognitive training - for the past few years, and he believes it is helping.

"Just knowing this information is empowering," Roberts said. "I'm much sharper now after the cognitive training than when I was just sat there worrying about it.

"Now it's about trying to stay positive and taking responsibility for your own health.

"I can't live in the past thinking what should have been done by the sporting body itself. I have to move forward from this and improve my mental health."

What is sport doing about concussion?

In 2016, 5,000 former American football players successfully sued the NFL for $1bn (£700m), claiming it hid the dangers of repeated head trauma.

Top NFL officials have acknowledged a link between head trauma in football and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) following a 2015 study into the brains of deceased ex-NFL players.

In rugby union, Premiership and Championship players in England are taking part in the development of a pitch-side test to diagnose concussion and brain injuries during the 2017-18 season.

World Rugby also introduced heavier sanctions for high tackles in 2017 in an attempt to lessen the incidence of concussion in rugby union.

In January 2018, the Football Association began a study into the links between heading a football and brain damage.

- Published17 April 2017

- Published20 July 2017