Did England squander their 2003 Rugby World Cup legacy?

- Published

How quickly a decade can pass. 10 years ago this week, Jonny Wilkinson's right boot won England the World Cup final, and all seemed sweet in the garden of the red rose.

And now? In the intervening years, England have failed to win a single Grand Slam. In the same period, Wales - with less than 15% of their cross-Severn rivals' pool of senior male players, and significantly less than half their annual revenue - have won three.

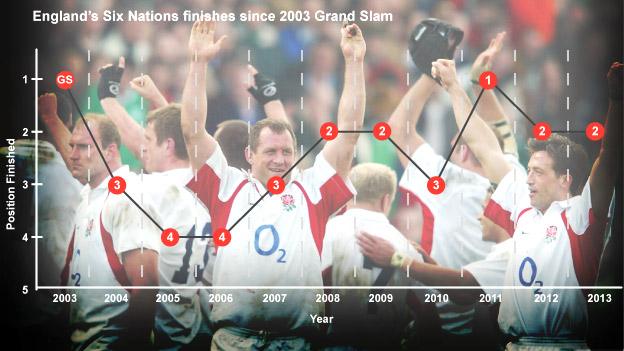

In all that time, England have only once topped the Six Nations table. Twice they have finished fourth. At grassroots level, there are fewer people playing rugby in England than there were in 2003.

Has this been the most inglorious of wasted decades? Why did that night in Sydney represent a lone peak rather than signify the start of a prolonged period of ascendancy?

Let's start in the foothills, for the ripples from Australia were felt here almost immediately. In the first full year after that World Cup win, an extra 5,500 kids between the ages of seven and 13 began to play rugby in England. The following year it climbed by another 9,000.

In the five years between 2003 and 2008, participation numbers in that age group would increase by a remarkable 78%. For 13-18 year olds, the pattern was repeated, albeit on a slightly smaller scale: numbers climbed 49% in the decade to 2008.

The effect is starting to surface at the elite level. Marland Yarde, the 21-year-old winger who made his home England debut at the start of the autumn series against Australia, saw rugby for the very first time on that morning in November 2003.

"I loved the passion there was for that match, and how it affected the mood of the whole nation," he told me last month. "For the first time I thought 'this is a sport I could take up'."

So significant was the trend that it even had a name: the Jonny Effect. But there was a problem: what happened when the kids showed up?

"Without a shadow of a doubt, we saw it," remembers Rory Davis, now chairman of the Old Albanians club in Hertfordshire but back then in charge of the junior sides.

"It wasn't just the kids who had watched it - there was more awareness among parents. The mums liked Jonny. The only disadvantage was that everyone wanted to drop goals, and as coach I didn't want my props dropping goals."

Old Albanians, with one of the strongest mini and junior set-ups in the country, were ready for the invasion.

"What we felt as a club was that we had to sustain it," said Davis. "My view was that you need at least one coach for every five or six kids. Especially with the little guys, you can't keep their attention unless they're in smaller groups. They will go and pick daisies."

Few others were so well prepared. Many lacked the coaches, pitches and equipment.

Before the 2007 World Cup, the Rugby Football Union (RFU) would launch their 'Go Play Rugby' campaign, aimed at bringing lapsed 18-30-year-olds back into the sport. In December 2003, the Webb-Ellis trophy was sent on a retrospective tour of the country. That apart, grassroots development was left almost entirely to chance. When assistance from above did come, it was reactive rather than proactive.

"It was after the horse had bolted," admitted Steve Grainger, appointed RFU rugby development director two and a half years ago to ensure the same mistakes will not be repeated when the World Cup returns to these shores in 2015.

"It [2003] was on the other side of world, we didn't expect to win, and all of a sudden we won. Those who were here in '03 would say that there weren't enough coaches or facilities in place.

"There is no doubt that the mini and junior boom that happened in those years has set the game up very well. But our biggest problem now is hanging on to 16-24 year olds. It's not just a rugby issue, but that's not an excuse."

At the elite level, the decline began almost immediately. The spring after the World Cup, England would finish third in the Six Nations table. The following year they would drop to fourth, and remain there in 2006.

"There was an element of frustration for me because of what you had come to expect from the England rugby team," reflects Matt Dawson, scrum-half in that final and on 76 other occasions for his country. "When you turned up, when you went on tour, you expected that people would deliver, that they wouldn't be making mistakes.

"But after 2003 we were a very different side. When forwards like Martin Johnson, Jason Leonard and Neil Back all went - they were so crucial to the way we played. We all understood each other.

"In a game, thousands of decisions are being made, but it only needs a few to be the wrong ones for the team's fortunes to reverse."

And reverse they did. England had famously gone into the World Cup on the back of an unbeaten home run stretching back 22 games and four years. It was to last not a single match longer.

"There was a natural turnover of players, because a lot of us had come together at the same age," said Dawson.

"But the first time we played Ireland in the very next Six Nations [losing 19-13 at Twickenham], external it had started. And when you lose games, you lose confidence.

"When it goes, it goes quickly - 18 months down the line we had lost the reputation of being World Cup winners. We were a different side, with a different coaching set-up."

Head coach Sir Clive Woodward had departed, external before the first anniversary of the final, citing in his divorce irreconcilable differences with the RFU.

"It was clear to me that when we came back from the World Cup I felt totally out of control," he said at his valediction. "I wanted more, and we have ended up with less."

Under his replacement Andy Robinson the slump deepened. In the first 14 matches after the World Cup England were beaten nine times, including three defeats on the bounce in the Six Nations, their worst run in that tournament since 1987.

His defenders may point out that Woodward had, by his own admission, focused all his energies and resources solely on winning the World Cup rather than worrying about what came next.

But it worked. And when Woodward departed, ambitious budgets, left-field ideas and all, so too did England's success.

"Clive was very intent on taking it to the next level," explained Dawson, "but the RFU were not on the same page at that point.

"Where I would back Clive up was that the proof was in the pudding. Yes, the World Cup programme cost a few million pounds, but it paid back in spades in terms of sponsorship and ticket revenue.

"The powers that be decided that would not be the way to go, but Clive was vindicated by the fact that the years afterwards were such lean ones."

Did the World Cup triumph and its subsequent rewards satiate some of the players? You couldn't blame them if so; they would not be the first elite sportsmen to struggle for quite the same peerless levels of motivation having bagged the biggest prize in their sport.

As Dawson points out, no side in the history of the tournament has won back-to-back World Cups (it has not been done in the football equivalent since 1962). while 2007 winners South Africa went out of the 2011 competition at the quarter-final stage. At least England made it back to the final, external four years on from their own triumph.

There are those who think that England team had actually peaked in the months leading up to the World Cup, when they thumped Ireland in Dublin to win a Grand Slam, external and then beat both the All Blacks, external and Australia, external on their own turf. But Dawson does not believe there was any decline before the Webb-Ellis trophy had been won, citing the performance in the semi-final against France as evidence of their class.

"People forget that other teams learn from your big wins how you're going to play. And World Cups aren't often won by teams playing amazing rugby. Look at New Zealand in 2011 - they were hardly blistering in the quarter-finals against Argentina, and they struggled for long periods in the final against France.

"We had learned our lessons in the Grand Slam deciders of previous years that it wasn't about the performance, it was about the result. And that is the nature of the World Cup beast - win ugly or win pretty, it doesn't matter."

Around half a million people turned out in London to celebrate England's World Cup triumph

All these years on, Grainger is working hard to make sure the grassroots at least are not allowed to wither.

The RFU is investing £28.5m in the community game this financial year, and has 120 fully trained community coaches to deploy around the country where the need is greatest - for example, in persuading more 18-year-olds to play in the front row.

The task is a necessary one - 190,000 adult men play rugby regularly in England today, while in 2008 there were 230,000.

"You'll always inspire people with a World Cup win," says Grainger. "But what happens when they realise they're not going to make it at the elite level? That's my biggest challenge. How do we make sure that those people who come into clubs in November 2015 come back week after week, month after month?"

Rugby is not the only sport to have failed to capitalise on a golden ticket. Hockey clubs still talk about the sense of amazement as kids streamed through their doors in the aftermath of Great Britain's Olympic triumph in 1988, and their sense of powerlessness as they realised they had neither coaches nor equipment to keep them coming back.

But there is still a sense of regret that the World Cup party, for all its joy and wonder, was followed by so stinging a hangover.

"I do feel we didn't leave the legacy that we could have done in the game," added Dawson. "Supporters will always remember it, and lots of people got into the game. But we potentially could have done so much more."

- Published21 November 2013

- Published2 November 2013

- Published15 February 2019