Six Nations 2014: In search of the soul of Scottish rugby

- Published

It is a brisk winter's morning in the Scottish Borders. Sleet is in the air, a precursor of the snow that will sweep in overnight. So too is anger, and disappointment, and recrimination.

The other weekend, Scotland's once-proud rugby team (Grand Slams in 1984 and 1990, World Cup semi-finalists in '91, champions of the last Five Nations in '99) fell to a quiet yet ghastly death against the oldest enemy.

Not only did they fail to score at home to England for only the second time in 93 years, they conceded 16 penalties, missed 27 tackles and spent just 3% of the match in the opposition's 22. Funerals have been noisier affairs.

Neither was this an isolated humiliation. Scotland have won only two of their last 12 Six Nations fixtures. Only twice in the last 10 years have they finished above fifth place. Their last win at Twickenham came 31 years ago.

What has gone wrong? Four simple words, a thousand answers.

But when you are searching for the soul of Scottish rugby, there is an obvious place to begin: the small town that has produced more players for the national side than any other.

The heartlands

Up the M6, a swerve round Carlisle, onto the A7 and into Scotland via the scenic backdoor. There, cosied around the River Teviot, is Hawick - home of Jim Renwick and Colin Deans, of the great Bill McLaren,, external of 59 internationals right up to the most recent, flying full-back Stuart Hogg. And here we encounter our first problem.

"The base isn't wide enough; there aren't enough people playing the game," says club secretary John Thorburn, who was taught - like Renwick and 1990 Grand Slam hero Tony Stanger - by McLaren at Hawick High School, and is now sitting in his office surrounded by the great commentator's famous prep sheets and programmes.

Hawick's homely Mansfield Park ground has seen the first steps of an astonishing 59 internationals

"The Irish seem to have hundreds of thousands playing at school. We've got hardly anybody."

Some chastening numbers for you. At the last count, England had 166,000 regular male players. France have 110,000, Ireland 25,000, Wales 22,000.

Scotland has just over 15,000. Here in the Borders, the cradle of the Scottish game, a mere 1,940 adults play the game regularly. Nationally, just 57 of the country's 340 state schools put out teams for four or more year groups.

"It's really, really difficult to get kids involved now," says Thorburn. "They seem quite happy not to get involved in any sport, let alone rugby.

"Summer rugby would help, so they can play in shorts and t-shirts rather than being up to their eyeballs in mud. But the professional teams are an hour and a half away in the cities. There's not really anywhere for kids to aim at. It's hard for them to get in there and develop. The opportunities are few and far between.

"Talented kids are missing out. One or two make it through, and a few go down south, but we need more systems in place so that no-one slips through the net. We need better pitches and more of them."

Scotland players were once raised at Hawick's storied Mansfield Park ground, schooled in its famous green kit. Now the top level is as narrow as can be: only with the artificial amalgamations of Edinburgh and Glasgow can players test themselves against the elite.

The blazers

An hour and a half north, cold and concrete in the capital's south-western suburbs, is Murrayfield - physical home of Scottish rugby, scene of both triumph and disaster in its 90 years of blue-shirted battles.

On those Grand Slam afternoons of long ago it rang loud and fierce. On this bleak Thursday it is silent, the wind careering round the empty car-parks and chasing paper round the grey pillars.

Scotland have won the Triple Crown 10 times in their proud history. But in the 70 years since World War II they have won it only twice; in that same period Ireland have won it eight times, England 12 and Wales 13.

Despite that, Scottish Rugby Union chief executive Mark Dodson has set targets of winning not only the Six Nations by 2016 but also - and you may wish to re-read this - the next World Cup.

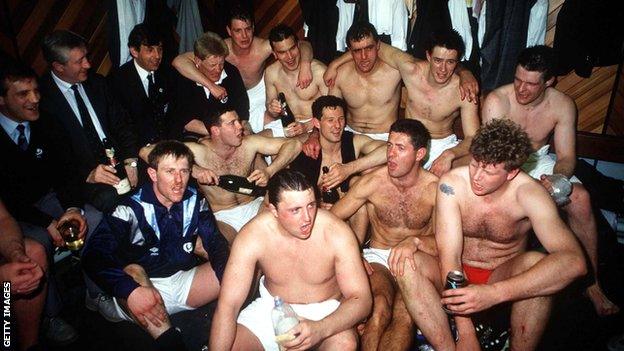

Scotland's third - and last - Grand Slam came when they beat England in 1990

Ambition is one thing. Ignorance of precedent and logic is quite another. Can the non-bombastic really envisage a time in the near future when Scotland - 52 of 72 matches lost since Five Nations became Six in 2000 - can win another title?

"Absolutely," says Dominic McKay, SRU director of commercial operations and public affairs. "Our ambition is to create successful winning teams. We're going to have the structures in place, we're going to have the coaching set-up right.

"We believe that with [new national head coach] Vern Cotter coming in the summer and some of the talent coming through the ranks, we're in good stead."

So much for the brave words. What of dispassionate balance sheets? The SRU's turnover in the last financial year was £40m. That compares to £153m at the disposal of England's RFU, and even £61m in Wales.

Of that small pie, the SRU spends £11m a year keeping Edinburgh and Glasgow afloat. A further £900,000 last year went on servicing the union's huge debt, run up by the move to professional rugby and the redevelopment of Murrayfield, down from a peak of £21m but still with £11m weighing heavy on the books.

"Professionalism was a struggle for Scotland," admits the personable McKay, sitting in an executive box high above the mangled Murrayfield pitch. "We've probably had a go at it four and five times, and not made a huge success of it.

"We're working really hard to make Glasgow and Edinburgh a success. There aren't terribly many people who are open to taking on a professional franchise in Scotland. It's something we'd be very open to, but at the moment we have to make the best of those two. It's a challenge for us."

The SRU has just announced funding for a new academy system, which with time (and cash) will see the establishment of four regional centres designed to find the best talent, hothouse them and bring them into the international set-up.

Whether this laudable aim can bear fruit is another matter. Of the 52 players in Edinburgh's squad, 17 are from overseas. Along the M8 in Glasgow, only 36 of the 43 players are Scotland-qualified, many of them only irregular starters.

Fly-half Tommy Allan starred for Scotland at under-20 level. Unable to get a contract from either Glasgow or Edinburgh, he took his ambitions elsewhere. He is playing in these Six Nations all right, but as Tommaso Allan, in the blue shirt of Italy, where he was born to an Italian mother and Scottish father.

The coach

And there is the conundrum. Pro teams must, by definition, be set up to succeed. In Scotland, funded by the SRU, they must also develop Scottish players. What if cheap imports give you a better chance of success than the local natives?

"I don't see it as being contradictory," insists Edinburgh head coach Alan Solomons, veteran of successful spells in his native South Africa with the Stormers and Kings and at Ulster across the Irish Sea.

"We need those young players to come into a settled team that is operating well. If they come into a team that is struggling, we will stunt their development. If the team is performing well, they will develop rapidly.

"You can build a team like [French European champions] Toulon - just throw money at it. We're not in a position to do that. But we are building a club, not a team, and we have to build it through our academies. If the system is operating properly you should have a steady stream of players. But we are always going to augment that with players from outside."

The lean Solomons, as passionate at 63 years old as he was in guiding Ulster to a three-year unbeaten home run in the Heineken Cup, cites the examples of 20-year-old scrum-half Sam Clyne and 21-year-old winger Damien Hoyland as two talented young Scots who are being carefully managed into the first team. There are also numbers further down the chain: in the last eight years, the number of youth players in Scotland has climbed from 15,000 to 31,000.

"I'm positive about it," he says. "I've seen it work at Ulster, and I believe it will work here. But I will fail unless I have a good team to bring them into.

"You need a strong, settled Edinburgh to bring through the development programme players. Surround them with experience. It's a win-win situation."

The legend

It wasn't always this complicated. When Doddie Weir was winning his 61 caps, he could be part of both a successful amateur club side at Melrose and a dangerous national one.

Now 44 years old, the old mischievous grin still on his chops, he is back in the Borders, up high on a green hillside in a landscape that feels more like New Zealand's South Island - sheep, snow, silent valleys - than easy urban Britain.

Early on a chilly morning, teapot on the go in his farmhouse's kitchen, he is as avuncular as ever. Neither does he want to rake his studs over a sport already in trouble. But the frustration is there, just as it is in the chests of many other proud compatriots.

"Scottish fans want to see a fight to the death," says Doddie Weir (centre), who never shirked a challenge

"Getting beaten in a game is sometimes acceptable, but you have to put in a great performance," he says carefully. "Against England that performance wasn't there.

"Scottish supporters want to see a fight to the death. That's what we've been brought up to do - that's the passion and pride we have, and sometimes that's the little bit extra the other teams don't have. Now whether it's the way the players are being coached or brought up, that has to be looked at.

"Scoring no points is very disappointing. But for me it was the manner of the defeat, and the skill level - missing a number of line-outs, missing 27 tackles. Is that an attitude or a skill problem?"

Weir bemoans the loss of his old Newcastle team-mate Dean Ryan from the Scotland coaching team. He also raises the same questions about head coach Scott Johnson's selections and tactics as many others. Why drop your captain Kelly Brown for the England game? Why leave out your best player, David Denton, for the next?

"When we played at Murrayfield, we played there four times a year," he remembers. "It was sacred turf. The changing-room was special. Now it's played on every week by Edinburgh. I'm sure it's still special, but that little spark is missing.

"Rugby is all down to attitude. If you want it you will do it. We should be unable to compete with England, France, Wales and Ireland. It's always been David versus Goliath. But we've also always had that one-off game.

"We expect to go into the game with full hearts and pride, and to me maybe that's the bit that's lacking at the moment.

"We would meet in the bar afterwards, and the supporters could come up to you - 'Hey Weir, you were rubbish today, you missed five line-outs…' You understood that. Now there's Twitter and Facebook, but you can turn that off. You can't turn off the bloke eyeballing you.

"I want everyone to be accountable for their actions. If they're successful they should be rewarded, if they're not, they should be changed. In the past that hasn't really happened - all the way through from players and coaches to officials. If targets are set and they're not reached, they've got to be moved on."

The grassroots

At times driving through the Borders you can feel as if you're on a tour of the Grandstand videprinter circa 1987 - Kelso, Selkirk, Galashiels, Jedforest. At others, criss-crossing the rivers on narrow stone bridges, you feel as if you're turning into Postman Pat.

Is this still the rugby country it once was? Melrose, Weir's old alma mater, was always the queen of this ancient scene - founded 127 years ago, home of the world's first ever sevens tournament, a town of just 2,500 people but source of so many great players from Jim Telfer and Craig Chalmers to present-day national skipper Brown.

Telfer played for and coached both Scotland and the Lions, attaining legendary status in the sport

The demographics are difficult. While the club's junior section is almost at capacity, there are few reasons for young adults to stick around. Unless you are in farming or social work, there is little prospect of long-term work. Melrose still runs two full men's teams. But many of those players commute down from Edinburgh for matches.

"Reading the Irish Rugby Union's new strategic plan, they believe that 72% of the population of Ireland feels rugby gives them a positive standing in the world," says Mike Dalgetty, director of rugby for 12 years, involved with the club since his 16th birthday 32 years ago.

"My opinion is that in Scotland 72% of people would neither care nor understand who we are or what we're talking about."

We are strolling around the Greenyards, Melrose's home since 1877. Inside the clubhouse are photos, pennants and caps of the famous rugby names who have played here. Outside the posts and old stand are painted in the club colours of yellow and black. On the dressing-room wall is the town's motto: "Truth and Honesty".

"When district rugby in the Borders was strong, all the big six clubs had international players," says Mike. "It was a compliment to the national game.

"Now it's an alternative, so you're splitting your players, your sponsors, your supporters. And there's only so much to go round. The professional game in any sport is a very greedy animal. It costs a lot to run something.

"I don't blame the current SRU for where we are. I think it's an accumulation of all the problems that have arisen over the past 15 to 20 years. They're beginning to deal with it. It's too easy to jump on the bandwagon and say we can't do anything right."

Does Melrose need a successful national side to stay alive? There is sometimes the complaint from those at grassroots that only the tall trees are nourished, that the clubs are given crumbs while Edinburgh and Glasgow feast.

Dalgetty is not a man lost in nostalgia. "There is no purpose to us being here if that national team doesn't count. If there was ever going to be relegation from the Six Nations, it would be disastrous. If Scottish rugby ever decides that it doesn't need a club like us, then we're as well giving up.

"In real terms, should we ever beat England again? It will only happen on certain occasions, and it will happen for the same reasons it's always happened - because we have a group of players with real heart and determination and particular conditions on the day. It will very rarely be because we have a stronger squad."

The past

So much for economics, for playing numbers, for financial statements and commercial operations. They can tell you a great deal, but they can't show you a sport's soul.

Which is why, before my wheels turn for home, I find myself outside a small house looking out across the Firth of Forth, shaking the hand of the man they call Mr Scotland. Literally.

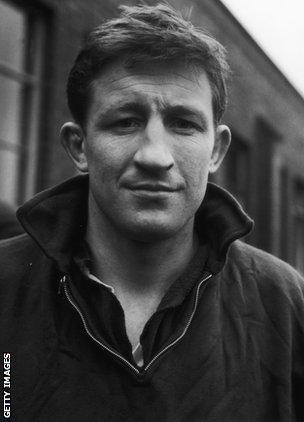

Ken Scotland, 27 caps at full-back for the national side from 1957-65, five for the British and Irish Lions, was described by Irish great Tom Kiernan as the finest player of his era, a dasher and weaver on par with Jackie Kyle and Barry John. Now 77 years old, he is still in the lean shape of many of his playing peers: v-necked lambswool jumper, strong handshake, unfailingly modest.

Ken Scotland shone for the Lions as well as his country - in 2013 only one Scot made the Lions Test side

"I was terrified to cross the road before the game in case I didn't make it," he says of his debut against France, aged 20, when he was called up out of National Service to knock over the drop-goal and penalty that won a famous victory.

"There were no games live on television. Aged nine, the first game I saw at Murrayfield was Scotland against the touring Kiwi side of 1946. I was so absorbed by the atmosphere that I had an ambition to play rugby for Scotland from that minute onward."

This was an era almost unrecognisable to his modern-day equivalents. There was no coach. There were no training camps. The team would come together on the Friday before a game, have lunch, "and then have a run around in the afternoon".

Neither was there sustained success.

"In my formative years, Scotland lost 17 games in a row between '51 and '55. The level of expectation wasn't particularly high. As players we literally took it one game at a time - there was never any talk that we might go for the Triple Crown. There was no expectation that we would win consecutive matches."

What the team did have was passion - a connection to the past, a fight for the future. When Scotland took on England at Murrayfield in 1962, 82,000 roared them towards a Triple Crown. The game ended 3-3.

"The way we were taught history at school was very chauvinistic, very pro-Scottish if not anti-English," says Scotland, sitting in a room decorated with team photos from every year he played, he and his team-mates looking impossibly slim and fresh-faced compared to the grizzled behemoths of today. "Wales and Ireland were Celtic cousins, but England was different.

"There was a Scottish style of play. Forward-orientated, in the face of the opposition, fairly unsophisticated, up and at 'em, don't let the opposition settle."

He smiles faintly at the memory. "Having been one of those supporters for years and years, watching the team bus coming into the ground... there's a pressure that it's your turn to be on the pitch.

"But you are tremendously proud and honoured, too. After a season or two comes a feeling of responsibility on top of that, that you're expected to give an example to those coming in. But you still feel the same honour and commitment."

The future

The snow that has been threatening all day is coming in hard, covering the country road, overpowering the windscreen wipers, threatening to extend the stay to another night. Perhaps I can knock on Doddie's door again?

There is passion and soul in Scottish rugby still. It's there in Doddie, in his wellies on his farm; in lifelong Mike at mighty old Melrose; and in John Thorburn at Hawick, all his spare time dedicated to his town and to the Bill McLaren Foundation's laudable work for the grassroots game.

Murrayfield itself, less a fortress these days than a slaughterhouse for Scottish dreams, is a poor incubator for all that hope and expectation. But the men who staff its offices are scheming, despite the tight financial restraints, and in Ken Scotland and his fellow self-effacing champions no more fitting inspiration for current and future stars could be found.

Pained Scottish faces - in this case prop Moray Low - are a common occurrence these days

But all that can only take you so far. On Saturday Scotland will meet Italy in Rome. Should they lose that battle - and their forwards will need to be vastly improved on that sorry Calcutta Cup showing to match the bellicose home pack - then another last place finish will feel almost inevitable.

And these men who hold Scottish rugby dear are ageing. Will kids with no memories of those Grand Slams and David and Goliath upsets, kids born with wooden spoons in their mouths, develop the same ardour for the game and nurture it as these men have?

Mike Dalgetty had it right as we sat on the old wooden benches in the grandstand at Melrose.

"We can't afford to make any more mistakes. We've made too many to this point. We have to squeeze everything we can out of what we do have: our players, our funds and our history."

You can hear Tom's interviews on Matt Dawson's 5 live Rugby Show on Thursday, 20 February from 20:30-22:00

- Published9 February 2014

- Published8 February 2014

- Published2 February 2014