Richard Parks: Conquering demons, depression and Everest

- Published

Pull down the duvet and what do you see? A floor? A ceiling? Four white walls closing in like a snowstorm? No horizons when you're stuck down a crevasse.

But look a little harder and you might be able to decipher the outline of a new direction. Towards a new relationship; a better job; a worthier challenge; the top of Everest - a metaphorical Everest or perhaps even the real one? If that sounds trite or dumb, it has been done. And if it has been done, it can be done again.

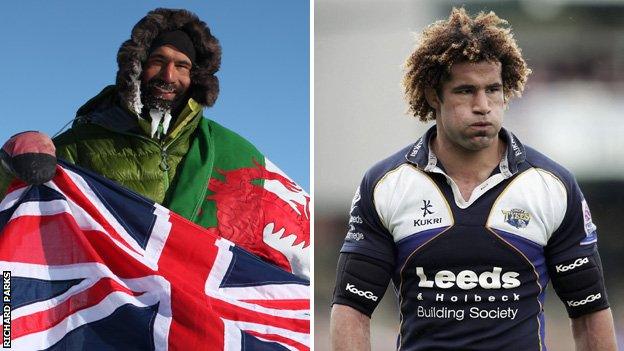

For former Wales international Richard Parks, the snowstorm began when he was forced to retire from rugby union, external in 2009, at the age of 31. He still had dreams but his body was no longer able to match his vigorous ambition.

Having been told his career with Newport Gwent Dragons was over - and that he would therefore win no more caps for his beloved Wales - denial set in.

"In isolation, reflecting and self-analysis can be a very difficult thing - but very enlightening as well"

There followed frustration and anger. He brawled in a nightclub, slept in his own vomit. Then, ashamed and embarrassed, he disappeared under a duvet and grieved.

"The bottom had fallen out of my world and it was one of the darkest places I'd been to," says Parks, who spent 21 days curled up in his parents' spare room. "There were so many emotions coursing through me and I didn't have the clarity of thought to make sense of them. And I wasn't able to let anyone in."

After grief came suicidal thoughts and crippling self-loathing. And then the outlines began to appear - of a new direction, towards a new beginning.

Two years earlier, at his nan's funeral, he had been struck by one sentence delivered by the vicar: "The horizon is only the limit of our sight." Parks had it tattooed on his arm, while not really understanding what it meant. But alone in his room, staring at his arm, the ink sunk in.

Life before climbing |

|---|

Born: 14 August 1977 in Pontypridd |

Position: Flanker |

Clubs played for: Pontypridd, Celtic Warriors, Leeds, Perpignan, Newport Gwent Dragons |

International career: Four caps for Wales. Two wins, two defeats |

Retired: May 2009 following shoulder injury |

"At last, I knew why those words were so important to me," says Parks. "I picked up a book by [British adventurer] Ranulph Fiennes, external and started reading. Along with the support of those close to me, the book allowed me to catch myself from freefalling and channel my energies into something positive."

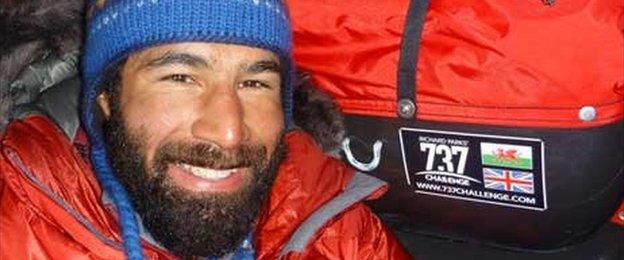

Parks is only able to find words to express his life in that small room because he has been curled up in a lot of small spaces since - not in his parents' house in Newport, but halfway up mountains, dangling down crevasses and marooned on frozen wastes. "It's just what I do now," he says.

On 12 July 2011, two years after crawling from his metaphorical cave, Parks became the first person to reach the highest summit on each of the world's continents and the North and South Pole in the same calendar year. It took him six months, 11 days, seven hours and 53 minutes. Not bad for a beginner.

"Falling as low as I did allowed me to aim as high as I did," says Parks, who raised hundreds of thousands of pounds for Marie Curie Cancer Care and has written a book about his experiences, Beyond the Horizon.

Parks has climbed Everest, Kilimanjaro, Elbrus, Vinson, Aconcagua, Carstensz Pyramid and Denali, and reached the North and South Poles

"Announcing the challenge was scary. There was a lot more chance of failing than being successful. Nobody had even attempted it and many thought it was impossible. But anything we do that is outside our comfort zone can be a really positive experience and it's important that people push themselves.

"What I did was testimony to what we can all achieve with belief, hard work and determination. That said, I just wanted to learn how to climb and get out of that dark place."

Parks believes the brutal nature of rugby union, which "requires a denial of the vulnerability or mortality of a player's career", allied to the strong bonds that are formed by a team's collective sacrifices make planning for life after retirement particularly challenging.

But rugby, somewhat ironically, provided him with many of the mental and practical tools to succeed in his new life.

"When I retired, I felt like I was losing many things," says Parks. "My self-image, self-worth, sense of community and family were all tied up with rugby. But rugby is still very much part of who I am and why I'm here and the integrity required to perform at the highest level still runs through me.

Parks's inspiration Sir Ranulph Fiennes is often described as “the world’s greatest living explorer”

"In the early stages it was too painful to be involved in rugby but now I'm able to enjoy it as a fan without the bitterness and pain. So while I don't feel like I've lost an old family, I have found a new one."

Parks calls himself a private person and says writing his story and letting people in was as difficult as anything he's attempted with ropes or skis.

And as difficult as writing about those 21 dark days in his cave was retrospectively admitting his vulnerability, halfway up mountains and marooned on frozen wastes.

On Denali in Alaska, Parks did actually fall down a crevasse. One of his big toes almost fell off on Everest, leading him to ask his doctor - in all seriousness - if losing it would at least make him eligible to compete at the Paralympics.

"In the world's most hostile environments, the consequences of mistakes are catastrophic," says Parks, who in January became the fastest Briton to ski solo and unsupported from the Antarctic coast to the South Pole. "So I wasn't able to have any self-doubt or vulnerability at the time. I didn't have that luxury."

"Anything we do that is outside our comfort zone can be a really positive experience"

Parks laughs when asked if he is masochistic. By most standards, he is. But despite living a new and impossibly exotic life as an 'extreme environment athlete', and admitting it can be an alienating existence, he is winningly open and inclusive.

But Parks's story provides lessons for people in all walks of life, even those who have no wish to almost lose a toe or actually fall down a crevasse. You don't have to learn to climb to get out of a dark place, but it will require the scaling of many mental ladders, ropes and cliffs.

But once out, you might be able to say: "That was then - but I wrote a novel/learned to speak Mandarin/mastered computer programming/went to teach abroad/became a cook/take your pick. It's just what I do now."

"Beyond professional sport, there are a lot of people who can relate to my experiences," says Parks. "Fewer people nowadays have a career for life, and that means more people having the rug pulled from under them.

"So many people are having to retrain and re-evaluate. So the ability to evolve, be resilient, and so many other skills we aren't taught formerly, are becoming more and more important. But that doesn't mean you have to scale Everest."

Pull down the duvet and what do you see? A floor? A ceiling? Four white walls closing in like a snowstorm? No horizons when you're stuck down a crevasse. But that doesn't mean horizons don't exist.

- Published12 July 2011

- Attribution

- Published27 May 2011