Six Nations 2015: Is patriotism still important in international rugby?

- Published

- comments

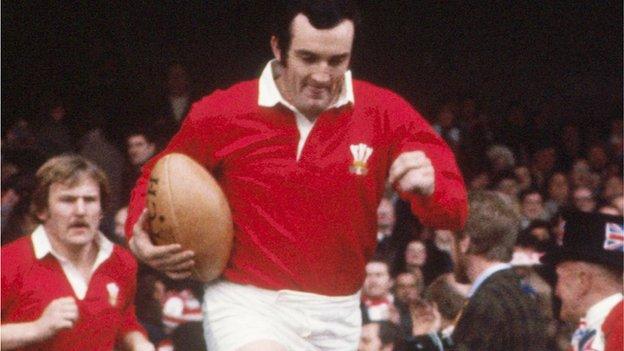

Fly-half Phil Bennett is one of the iconic players of Welsh rugby

RBS Six Nations - the opening weekend |

|---|

Friday 6 February: Wales v England (Cardiff, kick-off 20:05 GMT) |

Saturday 6 February: Italy v Ireland (Rome, 14:30 GMT) |

Saturday 6 February: France v Scotland (Paris, 17:00 GMT) |

"Look what this lot have done to Wales. They've taken our coal, our water, our steel. They buy our houses and they only live in them for a fortnight every 12 months. What have they given us? Absolutely nothing. We've been exploited, controlled and punished by the English - and that's who you're playing this afternoon."

This was how skipper Phil Bennett chose to ignite his red-shirted team-mates before Wales met England in 1977: a rousing oration to match the most stirring of sporting occasions.

It has become part of the narrative for this fixture. Us against them, flag around our shoulders, history at our back. Except 38 years on from Bennett's mischievous rabble-rousing, quite where us ends and them begins is rather harder to make out.

There will be fierce patriotism on display in the stands and heaving Cardiff streets. For two teams drawn from similar cultural and geographical backgrounds, it may be a little less red and white.

There is professionalism, there are postcodes. Of the Welsh team that will charge out at the Millennium Stadium on Friday night, almost a third were born in England.

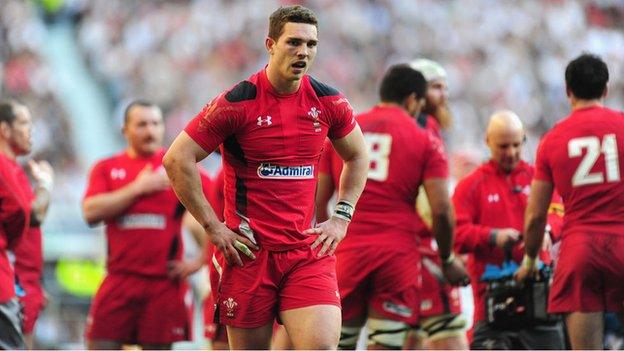

George North began his supersized existence in King's Lynn, Norfolk, centre Jonathan Davies in Solihull, West Midlands. Flanker Dan Lydiate was born in Salford, his fellow forward Luke Charteris in bucolic Camborne in Cornwall.

Alex Cuthbert originally hails from Minsterworth in Gloucestershire. Jake Ball - Ascot-born - once captained the Surrey Under-15 rugby team, and later emigrated to Western Australia as a promising fast bowler.

As current captain Sam Warburton said when asked, provocatively, about the supposed hatred between the two nations: "I have to tread very careful with this question, you have to remember my dad's English."

No-one would suggest that their birthplaces will mean any of those men giving anything but their all against England. Which rather shows how much has changed since Bennett sent his team out on fire and fumes alone.

Wales, with Phil Bennett to the fore, only lost to England once in 15 matches between 1965 and 1979

Patriotism is complicated anyway, a personal, nebulous mish-mash of myth, pride and occasion. And professional sport doesn't have much room for the nebulous, for the uncontrolled, for passion without a strict purpose.

"For someone in the Millennium crowd it's probably more important to beat England than to beat New Zealand or Samoa, but for the guy on the pitch it's important to go out there and win every time," says Colin Charvis, Sutton Coldfield-born but 94 caps for Wales, captain of his country on more occasions than all but three other men in history.

"As captain you don't focus on something personal. You don't make it anti another nation. I would talk to the players in the dressing-room about how the game was an opportunity, a chance to make a mark.

"In the 1970s the Welsh side was meeting the night before the game in the Angel Hotel and walking across Westgate Street to the pitch. Their build-up time was short and had to be much more intense.

"In today's rugby changing-rooms, you see players sitting down or walking around chatting. That talk is all about focus and what they want to achieve.

"The emphasis going onto the pitch is about what we want to do to stop them scoring points and to score points ourselves. You want focus and you want confidence, not fervour."

Wales flanker Colin Charvis played in an era of English dominance, only winning one of his 10 Tests against England from 1998 to 2007

For us supporters sport is often the easiest way into national pride - a simplification of those myriad versions of identity, a unification around a single idea and occasion.

No more north and south, no more young or old or right-wing versus left-wing or rich v poor. Instead, a shared shirt and communal song, a common enemy, a shared history.

It's what makes the Six Nations work as well as any other competition. Every game matters to those watching, no matter where the two teams may sit in the table.

It's fun too. Cardiff's St Mary Street and Chip Alley will see anthropomorphic daffodils raising pints to men dressed as Richard the Lionheart in soft-knit chain-mail.

Wales' thumping 30-3 victory over England in the corresponding fixture two years ago was a joyous, unforgettable party for every home supporter present.

For those involved on the pitch, often friends, sometimes team-mates more often than rivals, it is rather more complicated.

"Patriotism is big in our camp, we talk a lot about pulling on the blue jersey and playing with pride," says Scotland captain Greig Laidlaw, who plays his club rugby in the same Gloucester side as Wales' Richard Hibbard and England's Jonny May.

"A lot of the time it comes down to patriotism - the blood and guts, rolling up your sleeves and getting stuck in. We want to epitomise that in the Six Nations."

Equally, Laidlaw's squad contains fine players born in Zimbabwe (David Denton), New Zealand (Sean Maitland and Blair Cowan) and Swindon (Jim Hamilton), coached by a man hailing from the other side of the world (Vern Cotter).

A captain's task is surely more complex when leading so cosmopolitan a group. Quoting William Wallace has slightly less impact when Englishmen are providing you and your family with a very pleasant lifestyle.

Four of the Six Nations sides are led by overseas coaches - New Zealanders Warren Gatland (Wales), Joe Schmidt (Ireland) and Vern Cotter (Scotland) and Frenchman Jacques Brunel (Italy)

It doesn't have to mean less pride to be representing your country. It may just replace some of that famous warrior-poet Braveheart stuff with something more analytical.

"It's about the emotional tie to your jersey and your country," believes New Zealander Cotter, one of the four overseas coaches in this year's competition.

"The people who come and support you are very important. They provide the motivation. They strengthen the reason you do things."

Relish the support. Appreciate the history. And then, when the moment comes, go cold-hearted and dead-eyed.

"Players now are more focused on what exactly the process is to achieve the performance," says Charvis.

"Patriotism is not the key motivation. They've spent the best part of their lives trying to play professional rugby. They're all pretty motivated.

"I don't think patriotism is even a 1% advantage. Being able to focus on what you want to achieve is an advantage.

"It doesn't make you more aggressive. The aggression in rugby is matter of fact. Sorry to take the romance out of it, but you treat it as a necessity.

"It's your ability to do that that makes you a long-standing international. An Ospreys player will show aggression as part of the sport to a Scarlets player. You find your own motivation.

"Players are a lot more intimate with players from other countries now. England and Wales players know each other from the Lions. We know the New Zealanders socially, we play in England and France.

"The effort Alun Wyn puts into the anthem is all very important to the end result. It works for him."

"The rugby world is a much smaller place than in the 1970s, when some people thought you needed a passport to cross the Severn Bridge."

What of the moment the anthems are sung? For every mumbler in the team line-ups come Friday evening, the man staring silently at a patch of turf a few feet in front of him, there will be an Alun Wyn Jones: wild-eyed and roaring, arms physically binding him to his team-mates as Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau binds him to those singing with similar passion in the stands.

In that moment, is patriotism not inspiring him to a level of performance he could not otherwise achieve?

"You allow that atmosphere to help you realise how important the event is, and so add to your intent," says Charvis, "but you keep your focus.

"The effort Alun Wyn puts into the anthem is all very important to the end result. It works for him. But he doesn't spend all week at the intensity he's in during the anthem.

"The key is that you all come together, and that for those 80 minutes you work as hard as you possibly can to achieve that goal. That's what wins you matches."

- Published4 February 2015

- Published4 February 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published2 February 2015

- Published1 February 2015

- Published14 September 2016

- Published15 February 2019