Paul O'Connell: Farewell to a true Irish rugby icon

- Published

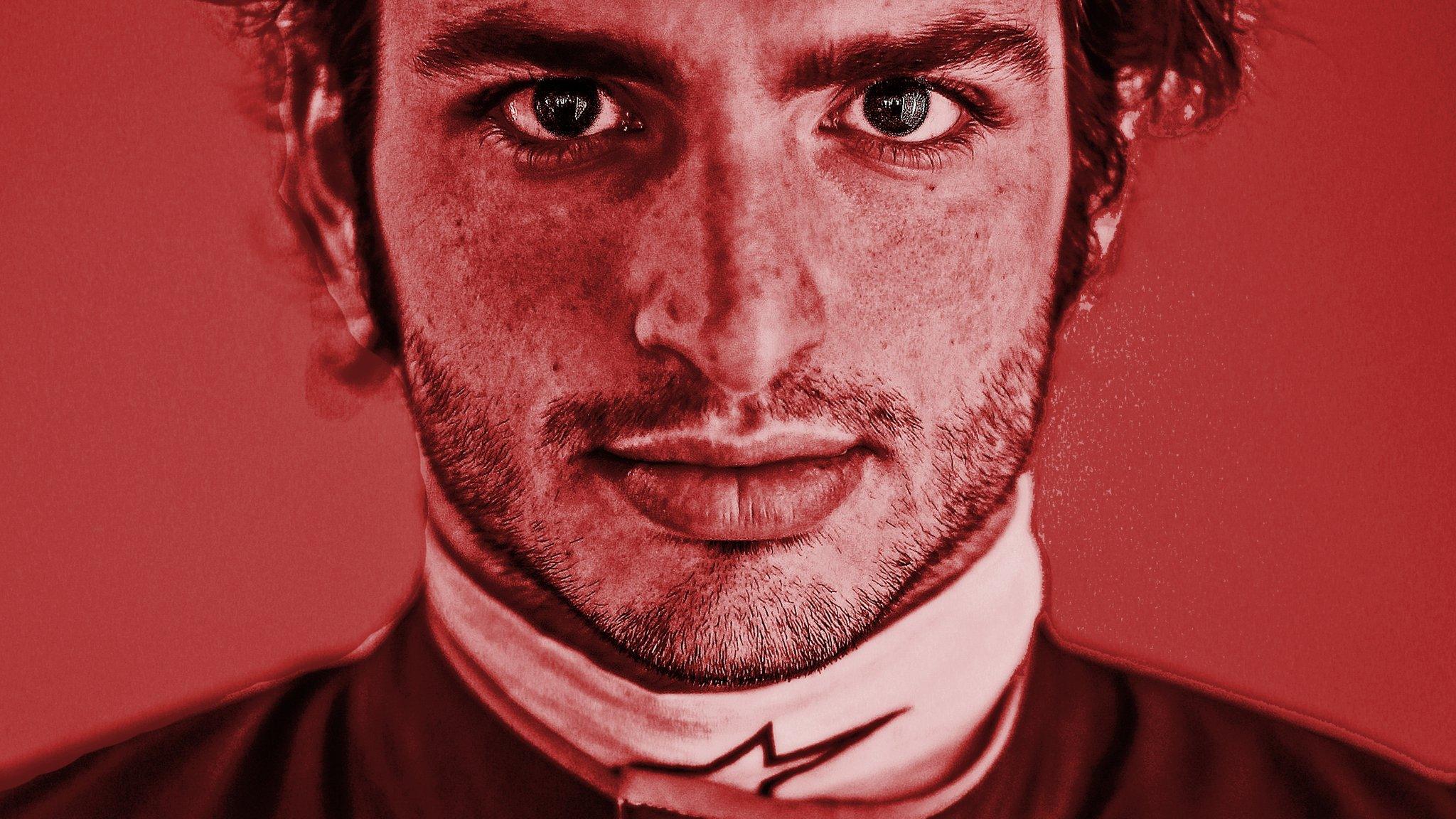

What rugby means to Paul O'Connell

You didn't need to see the replays to know Paul O'Connell's injury was a devastating one - all the evidence you required was there on the distressed face of a man who has spent his career hiding pain.

When O'Connell didn't get up in that fateful moment against France on Sunday, you knew it was over - his World Cup, his Ireland career, his dream of leading his country into a place it has never been before.

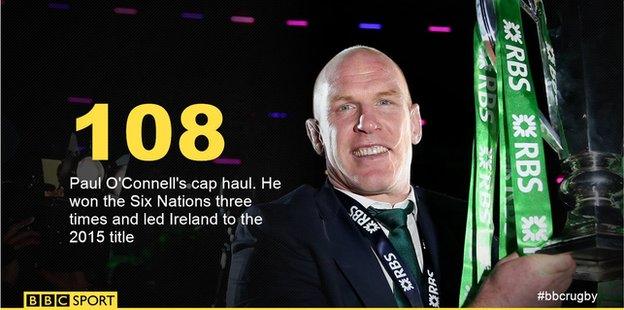

Ireland's bid to reach their first World Cup semi-final carries on without him. After 108 caps, and 13 years of setting standards like no Irish forward has ever set them before, one of the greatest of all Test careers is at an end.

It began, in 2002, with a bang on the head and an early exit on his debut against Wales and it has finished with the warrior once again carried away on his shield.

"You do your best by the jersey and you pass it on to the next guy," O'Connell told me when I was writing No Borders, an oral history of the Ireland rugby team. "We all have our time and then our time is up and everyone gets a little bit sad because it's over, but we're the lucky ones to have had that time in the first place."

In his stead comes Iain Henderson, a remarkable young Ulsterman who might not share the same province as O'Connell but is hewn from the same kind of granite. In Henderson we see part of O'Connell's legacy, the demonic will to win passed down to the next generation. It won't be the same, but the wheels will keep on turning.

It didn't matter how many caps he won or how many trophies he lifted, from the moment he burst on to the international scene, O'Connell was never happier than when talking about where it all began for him in rugby.

He basked in the memories of his early days at Young Munster, the working-class club in his native Limerick. Even as a Lions captain, a Grand Slam winner and a two-time Heineken Cup champion, O'Connell lit up most when he was talking about Young Munster. That never changes.

He was introduced to the club by his rugby-loving father, almost without realising it.

"We used to go into town for mass above in the Dominicans and we'd come out after mass and dad would be talking rugby to these guys and chatting about what happened in the All Ireland League. There was one particular pal of his who would always have a bag of sweets in his pocket and he'd chat to dad outside mass and myself and my brother would stand close by waiting for the sweets. You're not listening to what they're saying, but you're taking it in all the same."

The names that entered his subconscious were Ray Ryan and Peter Meehan, Young Munster's enforcers in the second row. There would be talk of Peter Clohessy, the fearsome prop, and Ger Earls, the tearaway flanker and father of Keith.

"Their whole thing was all about the physical challenge and that's all that anybody ever spoke to you about after games. When I started playing they didn't want to talk about your passes or things like that, they wanted to talk about rucks and tackles and mauls and scrums. I was immersed in it."

Paul O'Connell was a Munster fan long before he became a Munster player

In his late teens, O'Connell and his pals would "jump the wall" at Thomond Park to get into Munster matches for free. Not long after, he'd be driven in there in the team bus, pride of place alongside the titans of the age - Clohessy, Mick Galwey, Anthony Foley.

"Paul was like a newborn giraffe," recalled Galwey. "But he had that Young Munster hardness."

Eddie O'Sullivan, the coach who gave O'Connell his first Ireland cap, said he was a physical and mental colossus. "He just had that dog in him."

Over the years, two O'Connells emerged - the person and the player, and they couldn't be more different. The person is the most humble and normal bloke you could care to meet, utterly unaffected by his status as arguably Ireland's greatest and most beloved player.

The competitor is a different beast - scarily committed and hard working, brutally hard on himself and admired by his team-mates to such an extent they would run through brick walls for him, then rebuild the walls and run through them again.

They saw the lengths he went to in order to get an edge and that became the norm for all of them. When he was asked about his work ethic and his uncompromising mentality he would cite other lock forwards around the world and say he wasn't doing anything they weren't doing.

Maybe that's true but it was his reluctance to see himself as different that was instructive. Truly great players are more inclined to talk about their own weaknesses than they are to blow the trumpet about their strengths. And that was his mantra.

From his first day in an Ireland jersey in the spring of 2002 to his last in the autumn of 2015 he was never comfortable with talk of him being a superb leader which, of course, he was. Ireland's finest leader.

He told me about the things Irish fans never get to see; the moments of doubt and worry ahead of big games. He would have had the same feelings heading for the Millennium on Sunday. It was a recurring theme.

"I get stressed before games sometimes. I get a fear of the feeling you get when you lose. I get nervous and I don't want to be there anymore. You'd be looking out the window of the bus going to the match and there'd be fellas drinking pints and you'd almost be jealous of them. That feeling passes pretty quickly, but for a few seconds you wish you were out there with them having a sup of that pint."

Six Nations 2015: Paul O'Connell sets Ireland on their way against Scotland

His rightful place was in the dressing room, leading his team and setting the agenda, going to a deep place in pursuit of victory for fear of that feeling he got when he lost.

This is how he explained his mindset when things are at their most brutal in Test matches. "When you're in that situation, when the pain is coming on, in the back of your head you're saying to yourself, 'I'm getting better here. This is horrible, but I'm getting better'. When you're on the pitch, when you go to that place where your lungs are struggling and your legs are struggling, you know you've done the work, you know you can work through it."

You could find countless examples of moments when O'Connell's personality was pivotal to Ireland's success, but there was one from the Six Nations this year that does the job well enough.

Ireland had just lost to Wales and with it went their chance of winning a Grand Slam in O'Connell's final championship. The team was devastated, but there was one more game to go - against Scotland at Murrayfield - and a prize still to be fought for.

O'Connell's passion and physicality saw him lead from the front whenever he took to the pitch

"After the disappointment of Wales, Paul picked the team up by the scruff of the neck and carried it forward," said Joe Schmidt, the Ireland coach.

"He's our captain, our leader," said Johnny Sexton, the fly-half. "When Paulie speaks to the squad the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. I don't know if he knows how important his words are."

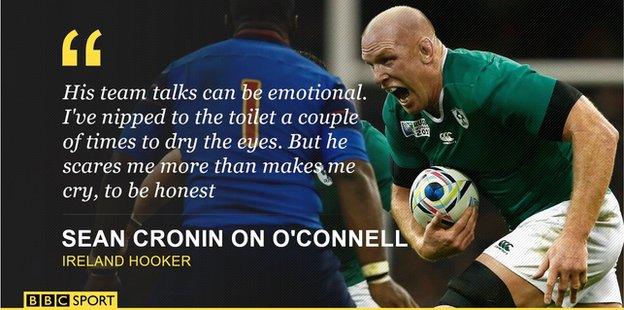

"Whenever Paulie plays he makes you play better," said Sean Cronin, the hooker. "It's the passion and physicality he brings and instils in the players around him. He sets the standard and you've got to get up there with him. He'll demand it of you one way or another. And his team talks can be very emotional. I've nipped to the toilet a couple of times to dry the eyes. But he scares me more than makes me cry, to be honest with you."

Ireland won that championship and took the Six Nations. In the moment of victory, one of his first thoughts was for England, who had played heroically in Paris and just missed out on the title on points difference. "They were incredible," he said of Stuart Lancaster's team.

On Sunday, before the France game, we're told that O'Connell's team talk was again inspirational to the point of players being in tears from the emotion. Too much emotion can be a bad thing, but O'Connell always knew how to judge it, when to pile it on and when to ease off.

As an Ireland player he only knew one way - forward. He'll not play for his country again, but what great service he gave and what immense years he had.

- Published13 October 2015

- Published12 October 2015

- Published11 October 2015

- Published11 October 2015

- Published11 October 2015

- Published11 October 2015