How English rugby is trying to build World Cup legacy

- Published

School children in Manchester have spent time with England head coach Stuart Lancaster and his players

Egg-shaped ball, backwards passing, 15 on a team and barely a pair of boots between them.

Rugby union to the uninitiated, football-fanatic teenager is a mystifying thing. But could a home World Cup in England change that?

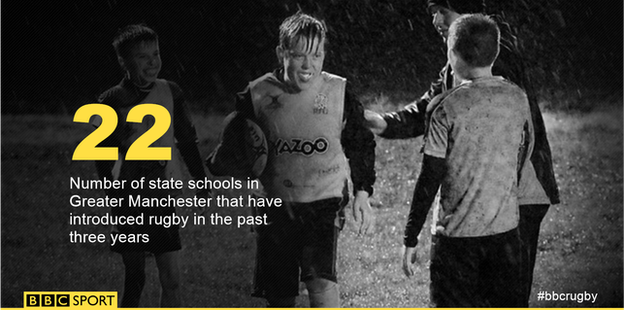

Some of the children at Loreto High School in Manchester could hardly afford boots when their PE teacher James Hyland introduced rugby three years ago.

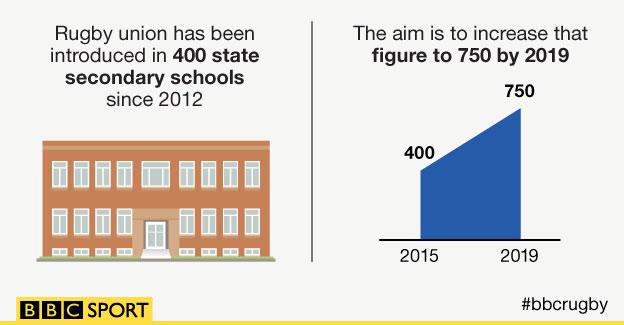

But the Rugby Football Union's (RFU) All Schools programme has enabled 400 state secondary schools, including Loreto, to afford to get rugby off the ground - as well as some footwear.

"The kids had never touched a rugby ball in their lives," says Hyland, whose school has gone from having no rugby union, to fielding a boys' team at every age level and fostering a link with local amateur club Broughton Park.

"We had our first training session and they were throwing the ball forwards, trying to trip people up as they went past and wearing their old trainers.

"It was starting with the basics. Some of them had never even seen a game on TV."

The boy who made a team

The lack of rugby at Loreto High School puzzled student Calum Conner Jones, a winger for Broughton Park, when he joined. So he did something about it.

"I asked if we could start a rugby team. I had a chat with Mr Hyland and they were all for it," says the 15-year-old.

"A lot of the boys weren't really bothered about rugby. They wouldn't have even known there was a club down the road.

"Now a lot of them go and play. One guy had never played before and after a year had a trial with Lancashire."

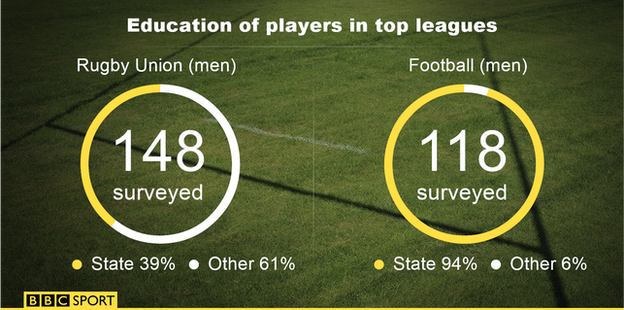

Union, for so long derided for its reputation as a game for the privileged, has struggled to gain traction in football-dominated state schools, particularly in the north.

"One of our greatest objectives was to change the perception that rugby is an exclusive sport - and it is a perception," says Steve Grainger, the RFU's development director.

"We wanted to really hit schools that perhaps rugby could have the greatest impact on - ones with low numbers of A-C grades at GCSE and free school meals - they're a good indicator of a school's social-economic background."

What's a breakfast buffet?

Source: National Governing Bodies of Sport Survey report for Ofsted, June 2014

Loreto, according to Hyland, has a diverse student population, with about "30-40%" from middle-class backgrounds and the remainder from "very deprived" backgrounds.

It sits on the fringes of leafy Didsbury and the poorer inner-city areas of Moss Side and Whalley Range.

Broughton's link with the school has seen the club stretch its demographic beyond its traditional, private school recruitment.

Last year, Broughton had six players in its under-six programme - this season they have 21. And most of their U15s and U16s players have come through the All Schools programme., external

"We are such a mix of social diversity. We have children that go to public school but we also have children that go to state schools," says youth secretary Pippa Ranson.

"They're out there and they just play. Some children have gone to grammars, some to comprehensives, they're still playing rugby together."

Three years ago, some of Loreto's pupils had never been to London, let alone Twickenham

Teacher Hyland came to realise the gap between the most privileged and impoverished of his students when he took a group on a funded trip to Twickenham.

"One boy lives with his granddad and has never been out of Manchester," says Hyland, who himself plays for North Manchester.

"I don't think he'd stayed in a hotel before and was like 'I've got my own bathroom?'.

"At breakfast he piled his plate with everything. He didn't understand the concept of a buffet breakfast - he had never seen one. That for me was the main eye opener of how deprived some of the children are.

"He's really come out of his shell now since playing rugby."

More World Cup reaction | |

|---|---|

A test of the World Cup legacy

There are, of course, gaps in the system. Loreto has undoubtedly excelled at starting rugby in the school because it has a PE teacher who is passionate about the sport.

Other schools would not have found it as easy - although just two schools of the 400 that have taken funding have dropped out of the system.

There have also been missed opportunities. The Uruguay squad used Broughton as a training base before their group game against England in Manchester, but none of the club's youngsters were given an opportunity to interact with the World Cup players.

That was, admittedly, down to tournament organisers and not the RFU - and local children did interact with England players in Eccles just days after the hosts' disappointing exit from the competition.

The story of the 2015 Rugby World Cup

Then there is the question of where girls fit into the equation.

The RFU says one in three children affected by the All Schools programme are girls - a figure Grainger describes as "light years ahead of where we were a decade ago".

Regardless of how corporate strategies and development targets are played out, the 2015 World Cup's biggest influence on youngsters could well be its spectacle - the action seen in stadiums and on TV from arguably the greatest union World Cup of all time.

Clubs were warned to expect an upturn in interest of 33% during the World Cup, although we might never know whether curiosity towards the sport was dampened by England's early exit.

Regardless, it is how that interest endures, years down the line, that will be the true test of the World Cup's legacy.

"The reports from rugby clubs I've been to have said they've had more youngsters come down," said Grainger.

"I've seen more kids throwing rugby balls around than I've ever seen before.

"If by 2019 we don't have more membership at clubs and more children playing in schools, we'll be saying it won't have worked. But I'll expect more people to be playing rugby."

BBC Rugby Union on Twitter |

|---|

For the latest rugby union news, follow @bbcrugbyunion, external on Twitter. |

- Published15 February 2019

- Published3 November 2015

- Published3 November 2015

- Published14 September 2015

- Published14 September 2016