Rugby World Cup: Is English rugby union just for posh kids?

- Published

- comments

Jason Leonard (left) and James Haskell and Chris Robshaw (both right) had differing schooling backgrounds

Rugby World Cup |

|---|

Hosts: England and Wales Dates: 18 September-31 October |

Coverage: Live commentary on BBC Radio 5 live and sports extra, selected local radio, plus live text commentary on every match on the BBC Sport website |

The Rugby World Cup will be a golden opportunity to take the game to new audiences in England. But with 20 of their 31-man squad at least partly educated in the fee-paying sector - compared to only 11 in 2003, when they won the Webb Ellis Cup - the BBC investigates whether rugby union in England is becoming more exclusive.

At the side of the A127 on the Essex-East London border, next to a ramshackle allotment, sits what looks like a bog-standard comprehensive. In appearance it is more Grange Hill than Eton. No gleaming spires here.

But the institution in question, Campion in Hornchurch, is arguably the finest pound-for-pound rugby-playing school in England - a lightweight mixing with the big boys, and regularly turning them over.

For the best part of 50 years, Campion has been a shining example to other state schools, especially those situated in rugby union's backwaters, that the sport is not necessarily the preserve of 'posh', privileged kids from fee-paying schools.

"I remember playing against a public school in the early 1970s," says John Davies, Campion's former first XV coach and the man who put more oomph than anyone into this unlikely rugby powerhouse. "I was standing next to our headmaster, 'Killer' Moloney, and someone shouted: 'Come on lads, they're only a comprehensive!' 'Killer' went mad. On the Monday, he called me into his office and said: 'Go and beat them all!' And we did, most of the time."

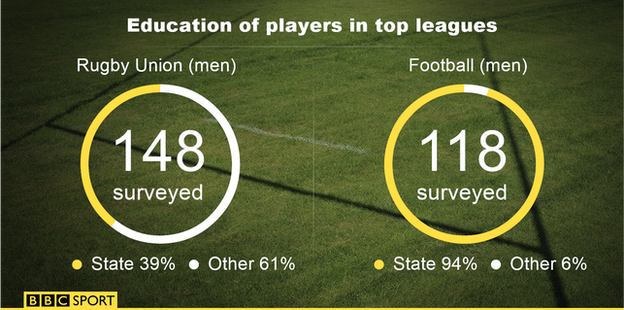

Source: National Governing Bodies of Sport Survey report for Ofsted, June 2014

But while Campion has shown what can be done with limited resources - it remains one of only two comprehensive schools to have won the English schools under-18s cup,, external which it did in 2001 - it also serves as a nagging reminder of how difficult it is for state schools to compete on a wonky playing field. Sweat, blood and blisters are key ingredients of sporting success - but having stacks of cash also seems to help.

A 2014 Ofsted report, external revealed that 61% of players in the English Premiership were educated at independent schools. Even allowing for the fact that 45% of those players were beneficiaries of scholarships (albeit often from other fee-paying schools) it is an arresting figure given that only 7% of English children are educated in the independent sector.

More from rugby: |

|---|

For the latest rugby union news, follow @bbcrugbyunion, external on Twitter |

Such statistics should be handled with care. There is a simple reason why the independent sector produces a seemingly disproportionate amount of top-class rugby players, and that is because most schools in the state school sector prioritise football over every other sport.

However, there is plenty of evidence - empirical and anecdotal - to suggest English rugby is still ignoring vast pools of potential. For example, the same Ofsted report stated that two-thirds of state schools visited failed to provide their pupils with any competitive sport at all.

Jason Leonard, an England World Cup-winner in 2003, went to school in Chadwell Heath, a couple of miles from Campion. And the winner of 119 international caps, now the president of the Rugby Football Union,, external knows better than most how sport in the state school sector is, and always has been, something of a lottery.

"We played soccer at my school, until one day a new teacher joined who was Welsh," says Leonard, who graduated from Warren Comprehensive to nearby Barking Rugby Club.

"He lined us up one day and said: 'I see on the curriculum you don't play rugby? Well, you will do next year.' I like to think I would have fallen into rugby somewhere down the line, but if it wasn't for that teacher turning up, I might not have found out what a great sport rugby was."

All Schools patron Prince Harry and RFU president Jason Leonard had very different school experiences

Just how many Jason Leonards have disappeared down the cracks? And, given Leonard's talent and size, how wide must those cracks be?

Not surprisingly, reaching out to boys and girls in rugby's traditional backwaters is dear to Leonard's heart. To this end, the RFU, determined that a World Cup in England should have a tangible legacy in the form of increased participation, has introduced a raft of initiatives in recent years.

The All Schools programme, external was launched in 2012 and aims to introduce rugby to 750 state schools by the time of the 2019 World Cup. It is an intelligent programme, with schools targeted in clusters so that they can grow beside each other at the same rate, allowing for evenly-matched, local fixtures.

Premiership Rugby, too, is doing its bit. On The Front Foot, external and Urban Rugby take the game to new audiences, with a particular emphasis on reaching women and girls, ethnic minorities and kids in inner-cities. Delivered through Premiership clubs with an educational and ethical bent, On The Front Foot had an estimated 310,000 participants in 2014.

Another crucial plank of the All Schools programme is the linking of schools to local clubs, so that talented players from schools with limited resources, and perhaps a fragile rugby culture, can benefit from more specialised coaching and those same coaches can work in schools to make that culture more robust.

Steve Grainger, the RFU's rugby development director, believes such link-ups are a necessity, because there is a "missed generation" of teachers who did not play rugby at school, often because industrial action in the late-1980s meant their teachers stopped volunteering for pre and after-school activities.

World Cup winners Jonny Wilkinson and Emily Scarratt are ambassadors for the All Schools programme

Ask John Davies the secret of Campion's success and he will not skip a beat. "It's all about the staff," he says. "It's not a one-man job."

At this point, I should declare a personal interest. As a Campion old boy myself, I remember its army of rugby coaches did indeed come from virtually every department. Davies himself taught biology and was head of the senior school. Maureen and Mary the dinner ladies would have manned the tackle bags, but they were too busy flipping chips and burgers - what passed as the lunch of champions back in the 1990s.

Davies - or 'JD' as he was known - was that rare thing, a small man with a formidable presence. The only pupils who gave him lip were mad or had presumably been at the altar wine. He was also inspirational. Where Davies went, people followed, whether you were a pupil or a fellow member of staff.

When he arrived at Campion in 1969, seven years after it opened, Davies was told by the headmaster: "There's enough soccer around here, this school should play rugby." Davies, one of many displaced Welsh rugby coaches in Essex at the time, was cock-a-hoop.

Having played scrum-half for the great London Welsh side of the 1960s,, external alongside Wales and Lions legends Gerald and Mervyn Davies, JPR Williams, John Dawes and John Taylor, Davies had plenty of connections. And so Campion's fixture list soon contained the names of some of the finest public schools in London and the South East.

But to achieve his aims, Davies had to be uncompromising. Public schools want competitive fixtures, and a full block of them, from first to sixth form. So pupils were told they had to play rugby, until at least the fifth form. "We used to say we'll be jack of all trades but master of one," says Davies.

John Davies (the small one in a white headband) was part of the great 1960s London Welsh side, which included seven Lions

This was pretty radical stuff for a state school in Essex, whose intake was predominately from working-class, often Irish, stock. But the lesson is clear: to have a chance of competing with the best as a state school, specialisation is advisable. Many parents who stood on the touch-lines didn't know what they watching, but they liked that their kids were winning.

In 1985, Campion played Australian Schoolboys and lost 13-0. On that same 16-match, unbeaten tour, Australia beat England 29-6. Scotland's Damian Cronin,, external England's Tony Diprose - both Lions - and Saracens legend Kev Sorrell are just three players to have rolled off the Campion production line.

In addition to their historic victory in the English schools cup in 2001, several years after Davies had moved on to pastures new, they were runners-up the following year and have reached the semi-finals on other occasions. Only two other comprehensive schools have reached the final.

Iain Simpson is still in awe of what Davies achieved. Now director of sport at fee-paying Oakham in Rutland, alma mater of current and former England rugby players Alex Goode, Tom Croft and Lewis Moody, Simpson played for Campion's first XV for three years in the 1980s.

Simpson remembers Campion well: the antique weights system, the misfiring showers, the scrum machine covered in weeds, the waterlogged pitches… and the absolute joy of being part of its rugby culture, which was an essential part of the school's identity.

"When I was at Campion, I didn't realise the magnitude of what 'JD' achieved," says Simpson. "When I look at the resources that go into a school like Oakham [it can cost up to £31,000 a year to go there] and compare it to the resources he had, which was close to nothing, I realise how special he was.

The changing face of the England team | |

|---|---|

England RWC squad 2015 | 20 fee-paying, 10 state, 1 abroad |

England RWC squad 2003 | 11 fee-paying, 18 state, 2 abroad |

England RWC squad 1995 | 14 fee-paying, 11 state, 1 abroad |

Figures for players educated in the fee-paying sector include scholarships | |

"But I also see similarities between Campion and Oakham. Look at any group of boys or girls that are playing sport together, enjoying it and achieving, and that will be because of a culture that has been created.

"That's not necessarily something you can buy. You get that culture because people are willing to invest time and energy, exactly like 'JD' and the rest of Campion's staff. That sort of sporting culture is integral to independent schools, but less and less so in state schools.

"My great sadness is that state school sport has gone downhill in the last 20 years. We don't play any state schools, because they don't offer the right level or quantity of competition. For lots of state schools, sport just isn't important."

Simpson says a few state schools that used to have fixtures against Oakham were heavily reliant on one inspirational leader - a Davies figure - and that once that leader moved on the culture ebbed away.

This sense of separation has increased since rugby union went professional in the mid-1990s. With many institutions in the independent sector now de facto feeder schools for Premiership teams and talented rugby players in the state school sector desperate to land scholarships, state schools have been left even further behind. Swingeing government cuts to state school sport have not helped.

Indeed, you wonder whether Davies would have ended up in a state school nowadays, given his qualifications - as well as being a former top-level player, he also went on to coach England's under-16s.

But he still might have struggled to land a job at Oakham, which has two former Leicester Tigers on its rugby staff (one of them a specialist sevens coach), as well as a full-time strength and conditioning coach.

"Independent schools are businesses and sport is an obvious marketing tool," says Simpson. "That's why independent schools invest a lot of money in trying to create teams that win."

Oakham does reach out to state schools, playing junior fixtures against them and sharing facilities and coaching expertise on occasion. But some believe independent schools, many of which have charitable status, should do more., external

Former Oakham pupils Tom Croft and Alex Goode lock horns in the 2011 Premiership final

At Robert Clack School in Dagenham, Jason Leonard's old stomping ground, Dave Maudsley is trying to prove that what Davies did in the 1970s can still be done. Maudsley is frustrated that his pupils are not competing on a level playing field. But he is trying not to get mad, wary of getting too chippy - and spurred on by getting even.

Robert Clack was traditionally a football school but in 2009 it set up a rugby academy. Its driving force, headmaster Sir Paul Grant,, external believed the core values of rugby - respect, discipline, team-work and enjoyment - were a perfect fit for his school.

In 2014, Robert Clack were crowned Essex champions in both XVs and sevens, despite having only 22 players to choose from.

Unlike Davies at Campion and Simpson at Oakham, Maudsley spends a lot of his time swimming against the tide. Parental support is minimal, pupils are not compelled to play rugby and traditional rugby-playing schools are not exactly queuing up for a Saturday morning trip to the mean streets of Dagenham.

"Prior to the academy being set up, many kids weren't interested in staying on after their GCSEs but we gave them an option to stay, continue their studies and play two more years of serious rugby," says Maudsley, a former public schoolboy himself. "But there is a constant worry about how many will stay on.

Essex rivals Campion and Robert Clack do battle, a fixture made possible by a passionate few

"When we started the academy, I faxed about 300 schools in the South East and London, telling them we were desperate for fixtures. We played 28 games that season, of which 25 were away, and went unbeaten.

"The following season, half those schools didn't want to play us, because we'd beaten some of them 70 or 80-nil. They came up with all sorts of excuses. And if any public schools nearby have been reaching out, I've missed their calls."

While Maudsley understands why parents of talented kids would want to send them on scholarships to independent schools, he says "independent school recruitment is becoming more and more cut-throat and professional". "It's bad form, an injustice," he adds.

However, just as state school boy Simpson says he would never work in the state school sector again, public schoolboy Maudsley is happy where he is.

"Rugby is not about winning games, it's about preparing my kids for life," says Maudsley. "Rugby is just a tool we use. Once you're on the field, it's simply 15 against 15. And when you're off the field, assuming you behave as young people should, you remain the equal of your opponents.

"We play these so-called posh schools and I think people are looking down their noses. You can see them thinking: 'We'll give these fellas from Dagenham a good hiding.' But they don't, and I get a real buzz from that.

"I've been on their side, and I know it's better on this side. Everything my boys achieve means so much more because they've had to work so much harder for it."

- Published15 September 2015

- Published14 September 2015

- Published14 September 2015

- Published13 September 2015

- Published13 September 2015

- Published3 February 2017

- Published18 September 2015

- Published15 February 2019