Adam Hastings: Son of Scotland legend Gavin forging own path

- Published

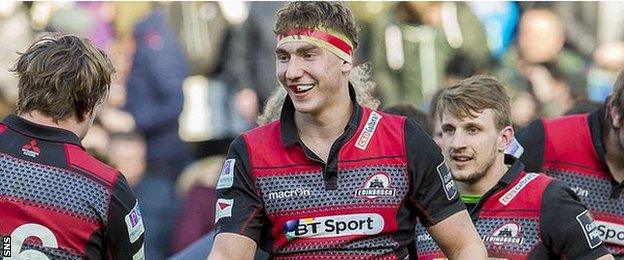

Hastings played three times for Scotland's Under-20s during their Six Nations campaign

Adam Hastings shrugs at the memory now, as if to chide his younger self for cooking up such a conspiracy.

He was greener then, his jet-propelled ascent through the sport that has shaped his life still on the runway.

Whenever he laced up his boots, the most iconic surname in Scottish rugby history - superhero full-back, captain of his country and the Lions - followed.

It spawned a sense of unease that gnawed at his conscience. Was he really any good? Or was the towering presence of his father Gavin thrusting him forth undeservedly?

"I did struggle with [the surname] when I was younger; I did let it get to me a bit," the 19-year-old recalls.

"Maybe a bit of attention I was getting was for that, not for other reasons. It was hard to know whether you were actually a good player or if you were just getting picked because of that link.

"But as you get older, you realise coaches are not stupid enough to do that."

To empathise with the son, you must consider the father.

To most in Scotland, "Big Gav" Hastings - 61 caps, a hatful of scoring records, 1990 Grand Slam hero, two Lions tours - was one of the finest players, perhaps the finest, to don the thistle.

Gavin Hastings scored 667 points in his 61 Scotland Tests, and a further 66 in six Tests for the Lions

But more than that, alongside brother Scott he was a national totem of strength and a symbol of identity, the very essence of Scottish rugby. When he wept on television after a sickening Calcutta Cup mugging, Scotland wept with him.

To Adam, he is dad.

"It doesn't bother me now," Hastings junior continues. "Although some people may think it's a burden, I think it's a great thing.

"It's nice to have someone you can talk to for advice, but I'm just trying to do my own thing.

"He was a great influence, always taking me down the park to kick a ball about - until he got a bit older and his back gave in.

"If I want to go to him and ask him stuff then he's always open to it - but I feel like the game's changed so much."

The inevitable comparisons feel grossly unfair to both the long-retired figurehead and the burgeoning progeny.

Aesthetically, at least, the hallmarks are evident. Teenage Adam has his father's frame (both are 6ft 2in), if not yet the meat to fill it out - topped with jet-black thatch, broad grin and granite jawline.

The lithe fly-half, all poise, swagger and flowing motions, garnered serious prominence during the Under-20 Six Nations campaign.

Hastings was a commanding figure on his maiden outing for the young Scots, a feverish first-ever win over England.

Hastings kicked two conversions and five penalties in three Under-20 Six Nations matches

He would have played more than three games in the championship, but Bath, in whose academy he is enrolled, required his services for Premiership fixtures against Worcester and Exeter.

"It has been mad; playing for the first team was a million miles away," recalls Hastings of his top-flight debut.

"It was so physical. Everyone is just absolutely massive - there's no getting away from it. You're found out in defence if you're not up for it.

"I think in the Worcester game I was targeted a wee bit. I was put through my paces fully in the contact area, but it was a lot of fun."

Gavin Hastings on son Adam |

|---|

"I am sure any father will tell you that your son listens to you as much as he wants to. I read a quote a while ago that said: 'By the time you realise your father was right, you probably have a son who thinks you're wrong.' I think there is a lot of truth in that! |

"My son will do his own thing. He is far more talented than me, playing at stand-off. He can learn a lot from [Scotland fly-half] Finn Russell - he would be a role model. And he's there at Bath with George Ford and Rhys Priestland, so he is in a good place to learn from some pretty good players." |

Hastings' berth at one of England's premier clubs is the latest stage in a prestigious rugby education.

It began at George Watson's, the school of his father and uncle, and progressed to Millfield in England's South West, a prolific producer of rugby royalty.

A glittering alumni list includes JPR Williams and Sir Gareth Edwards, legends of the Welsh game, England's Chris Robshaw and Jonathan Joseph, and Rhys Ruddock of Ireland.

"I fell in love with Millfield immediately; it's like a dream for a young person who plays sports," says Hastings.

"The main difference between boarding school and day school, even with Merchiston, external [an independent school for boys in Edinburgh] up here, is that you're training every day, so your skills are bound to come on.

"You're training day in, day out, you're always playing alongside each other, and always getting better. It tested me; it put me out my comfort zone a bit.

"But if there was a gap [between the Scottish and English age grades], I don't think it's there now. If there is, it's tiny."

Hastings is one of several young Scots tipped for a big future

Hastings now trains with George Ford, England's Grand Slam pivot, and Wales fly-half Rhys Priestland. He's surrounded by Test regulars, World Cup competitors from across the globe. He feasts on their wisdom.

"There are internationals at every position at Bath," he adds. "It's nice to have that quality around you, and pick their brains.

"Specifically, game management is the big one - Ford's kind of the master of it.

"In certain areas of the park, discussing different options to take and what the benefits of those are against the way different teams defend."

Though the Under-20s attained no more wins than Scotland's senior side, the latest batch of prodigies alongside Hastings kindles justified optimism.

There's full-back Blair Kinghorn and flanker Jamie Ritchie, excelling repeatedly for Edinburgh. Lock Scott Cummings has played nine times for Glasgow this season, and been rewarded with a professional contract. Prop Zander Fagerson's rise culminated in a senior debut in the Calcutta Cup.

Jamie Ritchie (centre) has had a series of starts for Edinburgh during the Six nations period

Open-side flanker Matt Smith is a titanic prospect, surely on the cusp of a professional breakthrough, while Rory Hutchinson and Robbie Nairn appear to be thriving, like Hastings, in two top English set-ups at Northampton and Harlequins respectively.

"You need to be exposed [to regular professional rugby]," explains Hastings. "If you're not, when you get a bit older, you're shocked, and then it takes a lot longer to develop.

"But if you're young and exposed to it, you can set yourself targets and know where you are in terms of being able to play at that level.

"I just want to get games under my belt - that's the biggest thing for me right now. When you stop playing and you're just training week in, week out for months, that's when your head melts a bit."

Still seven months shy of turning 20, it's a great deal more than a surname propelling him towards a bright future.

- Published23 March 2016

- Published22 March 2016

- Published7 February 2016