Scotland 25-13 England: Victory founded on passion, desire and fierce national pride

- Published

- comments

Six Nations: Scotland 25-13 England highlights

Sometimes the fiercest storm can blow in from the most cloudless of skies.

On a flawless day in Edinburgh, all golden winter sun and unbroken blue overhead, this was a perfect display for a celebrating nation.

And it was actually comfortable for Scotland - 25-13, in a fixture that England historically take routinely and without ever shifting into top gear.

No need for the rain and gales that Scotland have called upon to unleash hell on the rare occasions in the past 30 years when they have won this oldest of fixtures; no narrow six-point squeaker as in 2006, external and 2008,, external as when Duncan Hodge dived through the puddles in 2000,, external as in the most famous win of all, on Grand Slam day 28 years ago.

England had announced before the game that their players would be wearing special heated trousers, external to warm up their muscles for the ding-dong ahead. At £315 a pop they may wish they had kept the tailor's receipt. When the onslaught arrived, their temperature was set to half-baked rather than the scorched earth that came their way.

Scotland's biggest winning margin in this fixture in 32 years. No tries at home against England since 2004, and then three in the space of 21 minutes. England, lost in a black hole of Calcutta Cup, were goners long before the end.

Atmospheres have started well at Murrayfield in previous years. Then they have leached away, drained by the imposition of solid sporting logic, of a visiting nation with the playing and financial resources to gradually steamroller local hopes and dreams.

On Saturday, it started loud and got louder. Turnovers celebrated like tries, men and women on their feet punching the air after scrum penalties, knock-ons triggering bear-hugs and choruses.

"I wouldn't be able to tell you the history. It doesn't really affect me," said England centre Ben Te'o in the build-up. "What could a former player tell me about the stadium or the crowd? A lot of that stuff is pretty irrelevant.

"You're always going to have an away fixture with a hostile crowd, that's part of the game. You've seen one, you've seen them all."

Te'o, a veteran of seven State of Origin appearances for Queensland, of an NRL Grand Final with the South Sydney Rabbitohs, is one of many of his compatriots sent homewards to think again.

England lost the battle of the breakdown at Murrayfield, with Scotland flanker and captain John Barclay claiming three of his side's 10 turnovers on Saturday

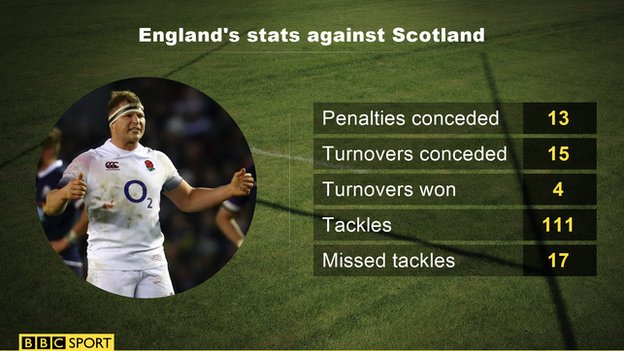

Scotland's triumph was built on their relentless breakdown superiority. Ten times they turned English ball over. It was aided by addled English defence - 13 tackles missed in the first half alone - and a spooked lack of discipline from those in white shirts, 13 penalties conceded by the flummoxed visitors.

But it was founded upon those less quantifiable variables, the ones that aren't meant to matter so much in a world of sports science and set-plays and overseas coaches and players switching nationalities after three quick years: passion, desire, fierce national pride.

Scotland could probably only have summoned this blue-shirted cyclone against England. If they play with the same liberation out wide and similar ferociousness at the breakdown they will beat other teams, but this was something more: that history which Te'o decried, the years of being on the wrong side of a rivalry that to England was beginning to barely qualify as a rivalry at all.

Accuracy, but ambition too. In the first half, Scotland made 327 metres with ball in hand to England's 166. They made five clean breaks. Guts, and the heart to go with it: 149 tackles against England's 111, Eddie Jones' men going sideways and into a blue wall almost every time.

The usual narrative for the defeated side after a horror like this is a positive one: they'll be better for this.

Six Nations 2018: Eddie Jones admits 'Scotland were too good for us'

Jones can point to a strong set-piece and a record that still reads 24 wins from 26 games. Others might point to the decision from referee Nigel Owens to rule out one English try for a knock-on in the tackle by Courtney Lawes and pull back another as Danny Care raced away for a breakdown penalty on Joe Launchbury, although Owens looked to have both spot on.

So the question must be asked: why should they be better for this? England were similarly shocked by the intensity and desire of Ireland in Dublin a year ago. It happened to Jones' predecessor Stuart Lancaster at least once a season, most memorably in Cardiff in 2013.

Seventeen of England's players on Saturday played in that defeat in Dublin. Mike Brown, Owen Farrell, Chris Robshaw, Dan Cole, Joe Launchbury, Danny Care, Courtney Lawes, Mako Vunipola and Joe Marler all played in Cardiff.

What was learned from those defeats that was utilised at Murrayfield? What changed in approach and personnel?

When the pressure weighed heavy on Saturday, when the scoreboard showed clear daylight, the thinking became muddled and the execution sloppy.

Jones said this week that England were "mentally tougher" than when they travelled north for his first game in charge two years ago. "We're developing a team that is robust."

Why then the poor pass to Jonny May on the left wing on the hour mark, and the spill from the winger into touch? Why did Lawes knock the ball out of Ali Price's hands from a ruck shortly afterwards, or Sam Underhill go in for a no-arms tackle to leave his side a man down with 15 minutes to go?

"We're humans, not robots," Jones told BBC Radio 5 live afterwards.

Other teams will also be unsettled if they meet Scotland in this mood. So too will England continue to show human frailties if they cannot learn to cope with these repeated lessons. When they had the ball they too often lost it; when they kept it, the attacking shape was poor, the coherency notable only by its repeated absence.

Huw Jones made 133 metres and four clean breaks for Scotland

Like the dog that looks like its owner, this Scotland team resemble the playing career of coach Gregor Townsend. They are harum-scarum, high risk, capable of conjuring tricks but of dropping the wand too.

They made mistakes against England, spurning drop-goal chances to buttress their lead, leaving points out there as when Peter Horne could not find Hamish Watson free outside him with the English defence exposed.

But they did so much that was right too.

In defence they were immense: Jonny Gray with 20 tackles, John Barclay and Hamish Watson 13, Stuart McInally 11. Barclay contributed three turnovers, Ryan Wilson two.

And in attack - and it is the attack that defines Townsend's ethos and team - they were relentless. Finn Russell kept the accelerator down. Sean Maitland caused panic down the left. Huw Jones - who also made 13 tackles, lest it go unnoticed - made 133 metres and beat five men.

If his first try owed a little to the luck of the bounce, his second epitomised where the contest was won and lost: quick ball, crashing through Farrell and Nathan Hughes; a gap opening up, the boldness and pace to take on the covering Brown and Watson; the skill and desire to fight through both.

The storm did not blow itself out. Logic did not hold sway. Scotland, this time, would not be denied.

- Published24 February 2018

- Published24 February 2018

- Published24 February 2018

- Published24 February 2018

- Published24 February 2018