Volvo Ocean Race: The highs and hazards of round-the-world sailing

- Published

ciszek_helm.jpg)

Beware of flying Blue Nose jellyfish. And sleeping whales. And fishing nets and fallen cargo, and tropical storms and shifting winds. The oceans are full of ghastly trouble and horrible hidden traps.

Competing in the round-the-world Volvo Ocean Race is not for the weak of heart.

Only certain characters can negotiate nearly 40,000 nautical miles of perilous seas on a cramped 65ft boat; sleep deprived, surviving on a diet of freeze-dried food and desalinated water for nine months.

How do they cope? How do they stay positive? Why sacrifice family life for a brutal slog in shark-inhabited waters? Members of Team SCA, the first all-female team to compete in the event for 10 years, give BBC Sport an insight into life on the ocean wave.

Four hours on, four hours off - it's not normal

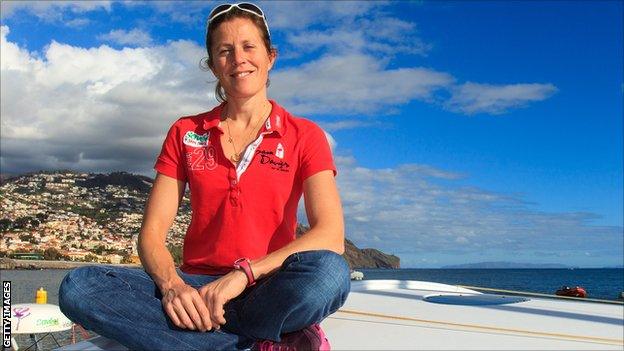

"Our day is not your average day because we're working 24 hours a day, seven days a week. They all roll into one." Sam Davies

Theirs is not a nine-to-five existence, but a life which revolves around a ticking clock and the rising and setting sun.

Simple necessities are squeezed into an ever-changing, ceaseless schedule. Sleeping? Eating? Resting? Only when necessary. Only to replenish and reboot.

"You can't really pick a moment when the day starts," says SCA captain Sam Davies, whose team are set to complete the second leg of the race, from Cape Town to Abu Dhabi, on Sunday.

They are currently sixth of the six crews still competing in the race, which started in Alicante in October and finishes in Gothenburg in June next year.

"We run a watch system, where we're sailing the boat on deck for four hours and then we have four hours off.

"For every eight hours we get two hours' sleep, but because we're always racing, if we need to manoeuvre or change sail it's all hands on deck which means you won't get four hours off."

Who are Team SCA? |

|---|

Only four female teams have competed in the race's 41-year history. More than 400 women applied for the 14 spots available (with 12 onboard in each leg). The crew began training 18 months ago. They are less experienced than their male rivals; just two have previously competed in the race. The team has three extra members compared with the male crews (nine apiece), a concession to the physicality of sailing's toughest race. The crew will be away for nearly nine months, with only the occasional meeting with family and friends during 11 dockside stops until the race finishes in June 2015. |

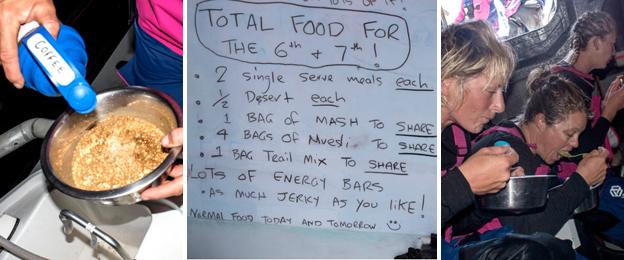

Today's special: dehydrated food - it's boring

"How do I describe the lamb? Dare I start with the colour? Grey with black dots. Ah yes, the rare spotted lamb meat." Corinna Halloran.

Eating like a king, or queen, is for some other day on a far away land. At sea, crew members must dine like astronauts, eating and enduring freeze-dried meats, but it's a period of weight loss rather than weightlessness.

Dee Caffari describes the diet as a "little extreme"; her team-mate, onboard reporter Corinna Halloran, , externalsays the freeze-dried ice cream is a dish which should only be tried once, while Sophie Ciszek , externalhas christened the second stint of the race as the "leg of the squishy meat". , external

"For breakfast we've got porridge. Lunch and dinner are all the same kind of stuff," says 40-year-old Davies, who will burn upwards of 5,000 calories a day for three weeks at a time.

"You do get bored of it, but it's fuel, it's a vital part of sailing well and going faster, so you can't skip meals even when you don't like them.

"Part of our training was taste testing all these meals so we've picked the meals we like the best, so we're pretty happy with it - although we're looking forward to some fruit and salad."

Lurking beneath - sleeping whales & coral reefs

"How do I tell my mother one of her worst nightmares has come true to another boat?" Corinna Halloran.

On a coal black December night in shark-inhabited waters, every sailor's worst fears became reality when, last week, one of the teams crashed on a remote coral reef and abandoned ship north-east of Mauritius. A human error, a costly shipwreck.

Team Vestas Wind waded through knee-deep water at daybreak and patiently waited to be rescued, while Team SCA were informed of the news by email, causing a sombre mood to descend on board.

The Team Vestas Wind boat stranded on its side after hitting a coral reef

"We can only imagine what it's like, it could have been a lot worse," says Caffari, 41, the first woman to have sailed single-handed and non-stop around the world in both directions, who joined the team for the second leg.

"We're in the hands of the winds and waves, but there are also unforeseen hazards.

"Whales sleep just under the surface of the water so we don't see them, but hopefully they hear us coming. There are also containers which have fallen off cargo ships floating just under the surface of the water."

Team SCA encountered a pod of dolphins during the second leg between Cape Town and Abu Dhabi

An hour to spare - to rest or email?

"We don't use the phone, except to speak with journalists. We all communicate with our families by email." Sam Davies

Each crew member was allowed to take a bag on board. "It's not a very big bag," explains Davies, fourth in the single-handed round the world Vendee Globe Race in 2008.

"It's a 40-litre bag and in mine I have five pairs of socks, some warm hats, long-sleeved shirts and my iPod."

Sam Davies with two-year-old son Ruben after the first leg in Cape Town

But the main purpose of the iPod isn't so the Cambridge graduate can listen to music or watch films, it's simply to scroll through photographs of her two-year-old son Ruben; a reminder of the biggest sacrifice this granddaughter of a submarine commander has made to test herself against the cream of the sailing crop.

"Usually, I'm so tired as soon as I get to my bunker I fall asleep, but I like to look at family photos," says Davies, a first-time skipper.

"We can email our families whenever we like, but we're sacrificing sleep and rest for it. Luckily, we have understanding families who send us emails but don't necessarily expect us to write to them every day."

Let it rain - it could be a good hair day

"A 'washable' cloud is when you're able to wet your hair significantly enough to lather and rinse your hair." Abby Ehler.

From the unpredictable waters of the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean's monsoons and the Southern Ocean's icebergs, there are an array of hazards to avoid and conditions to overcome.

The rain can be painful, like "small pebbles being thrown at your skin", but sometimes the squalling winds are a welcome relief.

"It's not a glamorous or comfortable environment," says Dee Caffari

"Whenever we get a rain cloud, it's fresh water, and the difference between just having a fresh water rinse or being able to wash the salt off your body is just an amazing thing," says Abby Ehler in the team's blog. , external

Caffari admits life on the boat is not for those who like their home comforts, bluntly admitting: "It's not a glamorous or comfortable environment where you get to change your underwear every day."

Racing in the dark - a whole new world

"It's like driving your car off-road in the dark without any light so you can't see anything out of the windscreen." Annie Lush.

On disorientating dark nights, when the sky is as dark as the inside of a cow's belly and there are no moon or stars to guide you, the sky and the sea becomes one.

"I really enjoy sailing at night," says Davies. "It offers a whole new level of sailing and I often have my best sails at night."

In a 24-hour period, each crew member will be on watch three times a day for four hours at a time, meaning everyone experiences the challenges of racing after nightfall.

"The biggest problem I find is you can't see the wind coming so you don't know when you're going to be hit by a gust and you can't see the waves," says 34-year-old trimmer Annie Lush. , external

"If the moon is shining, that makes a big difference but when it's so black you can't see the horizon, you can't see the difference between the sky and the sea. It can be very disorientating so you have to be really focused."

Short naps for optimal performance

"When you're in big stormy conditions, it's very consistent and that's when you get the best sleep." Dee Caffari

A carbon fibre bunk and a seatbelt - that is all that's needed for a peaceful hour of sleep.

The bunks are on either side of the boat, though the crew only use the windward ones, and each bed comes with the added feature of a seatbelt: no-one wants to see a sleeping crew member catapulted from one end of the boat to the other.

But choppy waters do not necessarily equate to ruined sleep.

"The hard time is when there's little wind," says Caffari.

"Everyone thinks you can relax but that's actually really hard work because you're working really hard to make the boat go fast. You need the weight of the inside of the boat to be moved around and therefore you're always constantly hard at work.

"When it's stormy, you've changed sails, the wind is what it is and you're in for the ride so that's when you get the best sleep."

But while the wind is great for racing, and not so bad for sleeping, unsteady legs turn making the bed into a 40-minute chore, and overworked muscles and limbs cannot be stretched and soothed as they should when the waves are swaying and dancing to an unpredictable beat.

"We all know anything can happen," says Davies. "It's something we've prepared ourselves for."

- Published4 December 2014

- Published13 October 2014

- Published1 November 2014

- Published9 October 2013

- Published18 March 2014

- Published1 May 2018