Happiness trumps Tour de France fame for ex-cyclist Philippa York

- Published

Philippa York: I'd have swapped cycling fame for earlier transition

Philippa York would have traded her success as champion professional cyclist Robert Millar to have lived as a woman from a young age.

Glaswegian York, 59, went public in the summer about completing her gender change more than a decade ago.

"I would have transitioned in my teenage years," she told BBC Scotland on her first visit to her home city in 20 years.

"And I wouldn't have been a cyclist and had the fame or infamy."

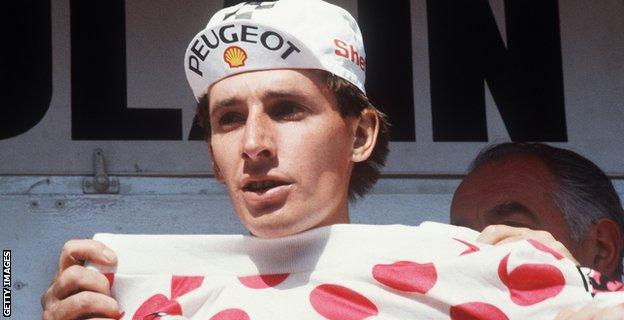

Millar won the King of the Mountains jersey in the 1984 Tour de France, finishing fourth overall, and was twice runner-up in the Tour of Spain.

But York admits she would have preferred to have lived a different life, having learned in her 20s that she could transition.

She said: "If I had the information that is available now to me back then, when I was on the cusp of trying to make a decision, I would have chosen to transition and not become a cyclist or whatever I became.

"But I realised it wasn't a practical thing, so I decided to wait until my career was over and, if I still felt the same, I'd do something about it.

"The thing that counts the most is not how famous are you going to be, it's how happy, and that counts more for me than any kind of success."

Robert Millar became the first British cyclist to win the famed Tour de France King of the Mountains jersey

York recalls suppressing the urge to change gender even at the height of her fame in the 1980s as Millar.

"There would be days during those years when I would be struggling with it," she said.

"You could be up there representing this powerful image and all the good things about sport but inside I'm a mess. The outside didn't really match the inside.

"I would compartmentalise it. When I did cycling I would do it 100% and that would cover the mental anguish I would have in my personal life.

"In professional sport there is no real place for emotions. That whole emotional system, I just turned it off and I operated like a robot.

"I would turn off my personal life while I did races and when I stopped the races I would have a couple of hours where I could turn back into what I call my normal person.

"I deal with my transition in two parts: Robert was the cyclist and Philippa isn't the athlete - she doesn't do any competitions.

"I'm happy - not perfectly happy, because I don't think perfection exists, but I'm fairly stable where I am and happy."

The story behind the interview

Sir Chris Hoy gave Philippa York and Rhona McLeod a tour round the Glasgow velodrome named after him

BBC Scotland journalist Rhona McLeod reveals what it took to persuade Philippa York to do her first TV interview.

Robert Millar, quite simply, was a sporting hero of my youth.

I was brought up in a home where cycling was practised and revered.

My parents instilled a respect and admiration for cyclists. In fact, as a baby, I was taught to say "allez allez, Gino Bartali" in support of one of the Italian greats of the '30s and the '40s.

But in the '80s, among the glamour of the Italians, French and Dutch riders, there was a Scot - Robert Millar.

I remember his shyness in interviews and his bobbing style as he dominated the mountain stages of the Tour de France.

Millar was the next stage in my cycling education as my dad explained the phenomenal achievement of winning the polka-dot jersey and being crowned King of the Mountains.

However, despite his success, Millar always had an uneasy air about him.

Some said it was arrogance and a permanent dislike for journalists.

Certainly the on-screen interviews could be painful and there were stories of him swearing at reporters if their questions or manner did not please the reluctant media star.

Then Millar seemed to disappear from public view. His career was over and he become reclusive, with only occasional sightings.

Philippa York: People who knew me before don't know how to treat me

The rumours started about Millar wearing pigtails and having breasts; tabloids attempted to doorstep him at his home in the south of England where he was living with his partner and young daughter.

A book was written, In Search of Robert Millar, but still the mystery was never solved.

That changed this summer when the Scot released a statement revealing his new identity, as a woman - Philippa York.

My interest was aroused once again and I decided to pursue the first television interview with York.

I managed to obtain an email address and we began our little dance.

I approached York, asking for an interview, and she asked for time to consider. I backed off and then, after a couple of weeks, returned to the task.

In the meantime, I believe York was checking me out with Scottish Cycling officials who know me and my work from various sporting events and Commonwealth Games.

The response must have been fair, as York agreed to proceed.

We spoke many times to set up the filming. We spoke of cycling, families, food and also of York's motivation to be interviewed in Glasgow, her home city.

It would be an incredibly emotional homecoming for her as she met one of the key figures from her past in his bike shop.

Former professional cyclist Billy Bilsland guided Robert Millar in his early career and met Philippa York on her return to Glasgow after a 20-year absence

Billy Bilsland was the coach, mentor and father figure who spotted the talents of teenage Robert and then provided the sage advice to send him on his way to the life of a pro rider in France. Millar gifted his 1984 King of the Mountains jersey to Bilsland and it hangs proudly in his shop.

Bilsland had not met Philippa and for the 70-year-old it was also a tearful reunion.

We later visited the Sir Chris Hoy Velodrome, where Sir Chris himself provided a tour to remember.

Both riders confessed to hero worship of the other - a humbling and emotional experience for both.

From a personal point of view, I greatly enjoyed Philippa's company and found her to be gentle, funny, giving and at all times interesting.

Most surprising to me were the tears and emotion - she seemed genuinely touched and bewildered by the plethora of good wishes and handshakes as we toured the velodrome.

York explained that the transition process was a painful one emotionally and that she felt our society in the 90s and start of the millennium was less prepared for, or tolerant of, people in her situation.

She last visited Scotland 20 years ago and I believe her homecoming was a positive experience for her.

- Published2 November 2017

- Attribution

- Published16 August 2017