Bobby McGregor: Scotland's last Tokyo medallist on saving a life & Olympic regrets

- Published

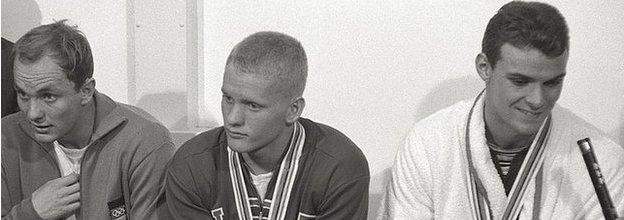

Scotland's Bobby McGregor, left, on the Olympic podium in Tokyo 1964 with his silver mdeal

Before his Olympic medal, his world records, and his Commonwealth and European golds, there was the time Bobby McGregor took a heroic plunge into a freezing Falkirk canal.

Had it not been for the youngster's quick thinking - or a pact with his father a year or two earlier - the consequences could have been tragic.

McGregor was the Scottish swimming legend who hadn't wanted to learn to swim, much preferring playing football to the thought of endless laps of the pool.

But his dad - a former Olympian - decreed he was only allowed to indulge his passion for fishing in the canal near their home on the condition he could handle himself in the water.

So when he and a pal selflessly dived to the rescue in their home town, a journey had begun that would lead all the way to the podium the last time the Olympics were held in Tokyo in 1964.

"I was very late - age nine - in learning to swim," says McGregor. "I mainly took it up so I could go fishing at the local canal, which my parents didn't like.

"Against their wishes, one day I went up to the canal with a couple of pals and we saw an old lady fall in. So two of us jumped in, pulled her out and took her back to her house.

"My father and mother only found out we had been there because the sons and daughters of this lady visited our house to thank us for saving their mother."

'I wasn't allowed to train in public sessions'

Having been coaxed into learning, McGregor quickly made up for lost time by displaying an aptitude that set him apart.

Progress was swift for the 'Falkirk Flyer' - within a year of starting to swim, he had won his first local schools title. By 16, he was a Scotland international. And by 18, he was winning silver in the 110 yards freestyle - Britain had yet to go metric - at the Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia.

As the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 loomed, it was clear Scotland had a world class talent. Unfortunately, the support structure provided by the authorities was anything but.

While modern-day swimmers are accustomed to state-of-the-art facilities at the Scottish Institute of Sport, McGregor had to make do with his local 25-yard public pool in Falkirk.

His father, who had been the sole Scot in Great Britain's water polo team at the 1936 Games, was by now Bobby's coach, and manager at Falkirk baths. But the notion of being granted special privileges was quickly dispelled.

"It was the only place we could train, but it was a public pool and the public came first," McGregor says.

"We put a lane up in one of the public sessions so I could train. Quite a number of the public complained, so my father was told I wasn't allowed to train during public sessions. It wasn't easy."

McGregor met similar resistance with a request to bring his father to Tokyo to help hone him for the biggest race of his life.

"At a council meeting in Falkirk, a proposal was put forward to send my father for five days," he says." It would have cost £2,500 and the vote went against it. That's what you were up against."

'I look back at my silver with regrets'

"I watched your race on television. It was very exciting and if you'd had a longer finger you would have won."

Not the words of a pundit or commentator, but of Queen Elizabeth II. When even the head of the British monarchy is offering commiserations it hammers home how agonisingly close you came.

Despite the less than ideal preparation, a 20-year-old McGregor had arrived in Tokyo buoyantly targeting gold in 100m freestyle final having set a new world record over 110 yards of 53.6 seconds a few weeks before.

"There were two world records at the time - metric and yards - and I held the latter," says McGregor.

"The main guy I was worried about was an American called Steve Clark, who I thought was the fastest in the world. But two months before the Olympics, he had appendicitis and needed an operation so had to pull out."

Bobby McGregor, right, was beaten to gold by Don Schollander, centre, in Tokyo

McGregor wasn't quickest off the blocks in the final and trailed slightly at halfway, but with 25m to go he surged into the lead. He was "just trying to hold on", but Don Schollander pipped him to glory by the tiniest of margins. It was one of four golds the American would win in Tokyo.

McGregor's silver, after clocking 53.4 seconds, was nothing to be sniffed at; he was Scotland's only medallist at those Games and returned home to a hero's welcome with hordes of people lining his street.

He was treated like royalty, right down to the visit for lunch with the Queen at Buckingham Palace. It was scant consolation at the time and, although the intervening 57 years have dulled the pain, it still lingers.

"My emotions were - I hate to say this - disappointment," says McGregor, now 77. "I got beaten by six hundredths of a second. If you talk to most people who win a silver medal at the Olympics, they'll not be happy.

"I look back and think I should maybe have taken a year off university or gone to America to train.

"David Wilkie - probably our most successful swimmer - tried to do what I did and win gold out of Scotland and couldn't. So he took a scholarship at university in Florida before he competed in his next Olympics, and that's why he won his gold medal.

"So you have some regrets, no question."

His second Olympics - Mexico City 1968 - brought a fourth-place finish and the end of his swimming career.

Tokyo remains a highlight, but is supplanted by McGregor's golden five-week spell of 1966 when he took silver at the Commonwealth Games and gold at the European Championships before breaking his own world record at the the British Championships.

Retiring from the sport he loves at just 24 seems abrupt, but McGregor's choice was stark.

"In 1968, I qualified as an architect from Strathclyde University and realised I just had to get on with my life because you don't make a living out of being an amateur swimmer."