Queen's 2014: Stan Wawrinka eyes improvement after Paris loss

- Published

If tennis had one shot to sell itself to the world, the Stanislas Wawrinka backhand would be a good bet.

As beautiful as it is destructive, former Wimbledon champion John McEnroe described the Swiss player's signature stroke as "the best one-handed backhand in the game".

"Thank you, John," says a bashful Wawrinka when it's put to him.

"That's my style, it's quite natural for me, but more important than looking beautiful is where you put the ball."

The 29-year-old put the ball in all the right places when he won his first Grand Slam title at the Australian Open in January, rising to three in the world rankings on the back of that win.

He became the first man outside the 'Big Four' of Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, Roger Federer and Andy Murray to win one of the four major titles since 2009, and only the second since 2005.

Wawrinka had roughed up the establishment, and yet he appears to be the one bruised from the encounter.

He arrives at Queen's Club this week looking to "put the puzzle back together" after a desperate first-round loss at the French Open.

Wild side

If Roger Federer has always appeared born to the role of sporting superstar, his compatriot and good friend sits less comfortably in the role.

The idea of embracing the big time and joining many of his contemporaries by moving to Monaco or Dubai does not appeal.

"I just enjoy living in Switzerland," he says. "I think it's a quiet place, a more or less safe place, a good life. I don't want to live in a big city."

Wawrinka grew up on his parents' organic farm near Lausanne, where they still help troubled children and the mentally and physically disabled.

"It was a really quiet place," he explains. "There were lots of animals and a lot of things to do - there were maybe 25 people working on the farm with the handicapped people.

"But it was perfect for me as a kid. I had the chance to work with my father; I really enjoyed my time. It's part of my life and part of my personality for sure."

While he might be softly spoken and enjoy the quiet life, Wawrinka is no wallflower. He enjoys the nickname 'Stanimal', a joke that hints at a wilder side.

Any player with such flamboyant strokes must surely have a creative, reckless streak, and in the last three years he has developed a love of skydiving and tattoos.

On his forearm he carries Irish poet Samuel Beckett's words: ''Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.''

Asked which was more terrifying - the skydiving, the tattoos or his first Grand Slam final - he thinks for a moment.

"Maybe the first tattoo. Because when you do your first one, you're doing it for life, so you have to be sure that it's the right one in the right place."

Pressure point

Wawrinka was eight years old when he took up tennis at his local club under the tutelage of Dimitri Zavialoff, who was only a teenager himself, and that partnership lasted until 2010 when the pair went their separate ways.

In his mid-20s and having been as high as nine a couple of years earlier, Wawrinka feared he had gone as far as he could.

"I had some moments where I was thinking maybe that's my best tennis, that's my best game, and that's it.

Stanislas Wawrinka won the Junior French Open in 2003

"I always put too much pressure on myself. I always want to do everything perfect and play my best game every match, but it's not possible. Sometimes you need to accept and do your best without playing your best game."

In the space of two years years he split with the man who had guided him since childhood, got married to Swiss TV presenter and model, Ilham Vuilloud, had a daughter, Alexia, and then announced the couple were separating.

Since reconciled, they are learning to manage the conflicting demands of family life and a globe-trotting profession. They will not be following the example of the Federers and taking the family on the road.

"Outside tennis my life is a little bit different with my daughter," he says.

"Travelling with the family is not always easy and my daughter doesn't like it. She's four years old and going to school.

"I have to find a good schedule because it's not easy for me travelling without my wife and daughter."

Wawrinka puts much of the credit for his leap from being a dark horse to a major winner down to coach Magnus Norman, the Swede who took on the role 14 months ago.

From taking Djokovic to five dramatic sets in Australia last year, and ending Andy Murray's reign at the US Open in September, to following up the Melbourne triumph with a first Masters 1000 title in Monte Carlo in April, Wawrinka's progression under the Swede has been clear.

"When I'm on the practice court I'm always trying to improve, to find solutions, to become a better player," he says.

"Working with Magnus has helped a lot with that. Mentally speaking I have more confidence, I know what it takes. I'm really happy to work with him."

But, as Wawrinka says, it is now time to "put the puzzle back together, find solutions, because the pressure is different".

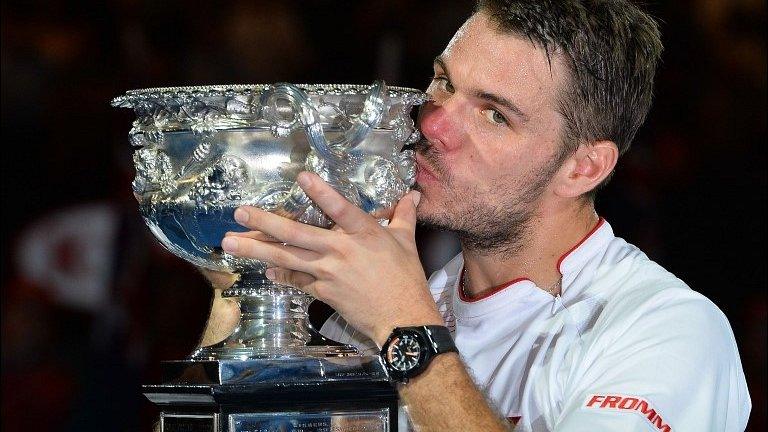

Stanislas Wawrinka won his first and only Grand Slam with victory in Australia in January

The backhand

Wawrinka's last appearance on court, on a dank and gloomy Parisian evening, was a disaster.

The French Open third seed was more in danger of clipping the line judges than the lines as his radar malfunctioned spectacularly against Guillermo Garcia-Lopez, and the last two sets raced past him 6-2 6-0.

He racked up a crippling 62 unforced errors in a performance so poor it was hard to believe this was the same player whose shot-making had left Murray, Djokovic and Nadal helpless in the previous two Grand Slams.

If Wawrinka is to put the pieces of his game back together in time to challenge for a second major title at Wimbledon, he will need to start with that backhand, the bedrock of his game.

And yet one of the few shots guaranteed to draw a ripple of gasps among those seeing it in full flow for the first time might never have seen the light of day.

"I changed my backhand from two-hander to one-hander at 11 years old with my first coach, Dimitri.

"He asked me to try as for him it was more natural to play one-handed, but it was difficult for me at 11 to play one-handed because you don't have that much power."

Like a child setting out on a bike without stabilisers for the first time, the absence of that second, guiding hand led to a few wobbles along the way.

"It's not easy, but Dmitri was always behind me, saying: 'It's going to take time but it's going to be better in the end,'" says Wawrinka.

"And he was right."

- Published29 May 2014

- Published26 January 2014

- Published26 January 2014