Wimbledon 2014: Grand Slam heroes become super-coaches

- Published

They have been called the super-coaches: the Grand Slam heroes of a generation ago, hauled away from the golf course and commentary box to adorn the entourage of today's ascendant stars.

Roger Federer has Stefan Edberg. Novak Djokovic has Boris Becker. Andy Murray, after Ivan Lendl, has turned to Amelie Mauresmo. It goes on: Kei Nishikori with Michael Chang, Marin Cilic and Goran Ivanisevic, Milos Raonic and Ivan Ljubicic.

And here's the first contradiction. What do you associate with the idea of coaching - tuition, certainly; hours of hard work in training; a dedication as intense as any other professional career?

By which measurements, these coaches are not coaches at all.

Most of these people will spend no more than 10 weeks a year with their players. Most have never previously held any sort of coaching position, and certainly have no official qualifications. Bound by the game's strict protocol, none can communicate with their charges during matches.

Neither is their influence obvious to the casual eye. Federer has not suddenly become an instinctive serve-volleyer since hooking up with Edberg. You will not see Djokovic working on backhand drills with Becker - all his technical work is done by long-standing coach Marian Vajda.

"There are no major changes, and there will not be any major changes," said Djokovic about his playing style under triple Wimbledon champion Becker. "I will not start serve-and-volleying, because this is not the way I've been brought up or learned to play."

Boris Becker has given up his TV commentary duties to fully concentrate on Djokovic's Wimbledon bid

Boris Becker | Novak Djokovic |

|---|---|

Turned pro: 1984 | Turned pro: 2003 |

Career titles: 49 | Career titles: 44 |

Highest ranking: 1 | Highest ranking: 1 |

Grand Slams: 6 | Grand Slams: 6 |

This is about more than tinkering with a forehand or working on core strength and speed. It also has little in common with what a coach of a player outside the elite might require. It is about finesse, about obsession with detail, about seeking every possible advantage.

"My role with [world number 58] Marinko Matosevic is taking care of things on court, looking at his general attitude," says Mark Woodforde, who won 12 Grand Slam doubles titles and five Grand Slam mixed doubles as a player and has worked with many big names, including Djokovic, as a coach.

Novak Djokovic's new coach Boris Becker wins Wimbledon in 1985

"You don't need to talk to Federer or Djokovic about their professional attitude. That's why they're up there, because they have fantastic ways of improving year after year.

"Roger, at this stage of his career, doesn't have time on his side but he still wants to improve. He can't stay out there as long, and physically it's such a challenge for him coming up against the younger blokes.

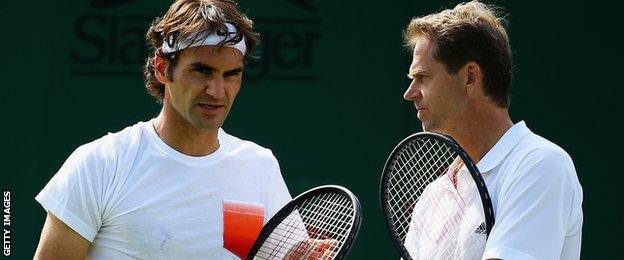

"Stefan was known for his attacking game, and what he's bringing to Roger is being more aggressive.

"It's not to turn Roger into a serve-volleyer, in every match from first point to last. But it's doing it at the appropriate times, so he's able to get through the first few rounds of majors with the energy and focus, so that he's not depleted, so that he can still win these major titles.

"For Boris, it's more a dinner conversation with Novak about how to approach certain points in matches. Boris was such a big-match player. If Novak can make those very small, incremental improvements, he can derive something from Boris."

Roger Federer will work with his childhood idol Stefan Edberg for 10 weeks this year

Millionaires like Edberg and Becker do not come cheap. Most coaches are paid a set fee by their player, with bonuses at the end of each season based on tournament performances. Others prefer to take a percentage of prize money. All will have their travelling and hotel expenses covered by the player.

Roger Federer | Stefan Edberg |

|---|---|

Turned pro: 1998 | Turned pro: 1983 |

Career titles: 79 | Career titles: 41 |

Highest ranking: 1 | Highest ranking: 1 |

Grand Slams: 17 | Grand Slams: 6 |

The more fundamental attraction for them - along with a little flattery - is knowing they, as Grand Slam champions, have experienced something very few others in the world can relate to. And that shared knowledge, that empathy, can be critical to today's elite players, cut off by lifestyle, fame and expectation from even the majority of their fellow players.

"I think we have been through moments, doubts, emotions, disappointments, joys - maybe some things that other coaches who are very competent as well didn't really feel or go through," says Mauresmo, who won the Wimbledon singles title eight years ago.

"I'm going to add a few things here and there, but I'm not going to teach Andy how to play tennis.

"These guys - it's important for them to talk the same language. And to know exactly what we're talking about. I would say we speak the same language in certain areas."

It is why having that famous face in your box courtside, even though they can offer only mute encouragement rather than strategic advice, is more than simply a glamorous accessory.

"As a coach, I don't enjoy it when a player asks me what is going on," says Woodforde. "You need to work it out yourself. Champions are self-made.

Andy Murray has said he thinks the feminine touch will help improve his game

Andy Murray | Amelie Mauresmo |

|---|---|

Turned pro: 2005 | Turned pro: 1994 |

Career titles: 28 | Career titles: 25 |

Highest ranking: 2 | Highest ranking: 1 |

Grand Slams: 2 | Grand Slams: 2 |

"But as a player, occasionally I looked at my coach. And sometimes it was the double clenched fist, sometimes it was just clapping. But that really did sink in to my psyche: I'm heading in the right direction."

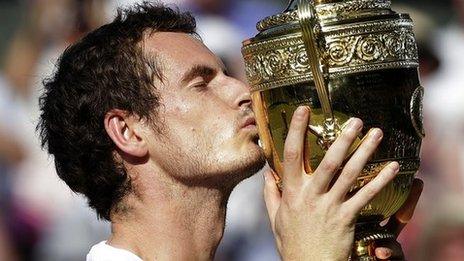

Murray was the first top-five player to employ a super-coach in eight-time Grand Slam winner Lendl. The success of their relationship - Olympic gold, US Open title, the Wimbledon victory a year ago - turned an eye-catching one-off into a trend.

At a time when the men's game is so competitive, when so little separates the top few players, no-one wants to be left behind.

"It is the small changes that can bring big results," says Woodforde.

"Ivan brought discipline to Andy Murray, at a time in his career when he needed to quit the moaning and start focusing. It's very hard to give your full attention to beating the guy down the other end of the court when you're fighting demons. Ivan was able to give him a distinct game-plan."

He also gave him confidence, just as Mo Farah's coach Alberto Salazar - himself a legendary distance runner three decades ago - did not create a potential Olympic champion so much as give him the belief he could beat his supposedly impregnable east African rivals.

Mauresmo keen on Murray 'challenge'

"Nobody makes a great athlete," Salazar has said. "Michelangelo once said that when he creates a sculpture, he just really frees the sculpture from the block of marble that's there. That great athlete was there; you get the athlete to bring it out of themselves."

We assume a player who has won six Grand Slam titles must therefore be bursting with self-belief. That is to forget the expectations that burden a player with the ability to win so much.

There is another statistic Djokovic considers more pertinent: he has lost five of his past six Grand Slam finals. To him, he is failing. So why not seek help from a man known for his ability to come through on big points in the biggest matches?

"Where he helps me the most and where I feel the biggest change is from a mental point of view," says the Serb.

"In terms of mental approach and a couple of other things, I find we have a lot of things in common. That's where I always look forward to talking with him, to get this necessary experience from him and use it in my own case."

Tennis players are not alone in looking for such psychological support. Golf, another individual sport defined by its cruel pressure on pivotal shots, has been using this entourage model for years.

Rafael Nadal has stuck with his uncle, Toni, who has coached him since he was a boy

It is why Justin Rose spent as much time with his mental guru Dr Gio Valiante before his US Open win in 2013 as he did with his swing coach Sean Foley, why Luke Donald leaned so heavily on performance coach Dave Alred, rugby union star Jonny Wilkinson's kicking guru, on his ascent to the number-one ranking.

These unusual partnerships can seem unnecessary or contrived to us outsiders or dabblers. Former England batting coach Graham Gooch used to make Ian Bell do press-ups between deliveries in the nets. Valiante made Rose repeatedly play out a scene from The Empire Strikes Back involving Luke Skywalker and Yoda the night before his final round at Merion.

But it can work. Gooch was teaching Bell not so much technique as maintaining it under pressure. Valiante was making a point about destiny. Both were taking experienced, technically brilliant sportsmen and getting them to learn afresh.

"The competition never sleeps," says Becker. "When I played, I consistently had to improve my game. It's the same with the top players today. They want to consistently improve and they have to find new ways to do that."

To which there is a logical follow-up. If having a super-coach makes such a difference, why is it that none of the stars in the women's game are doing it?

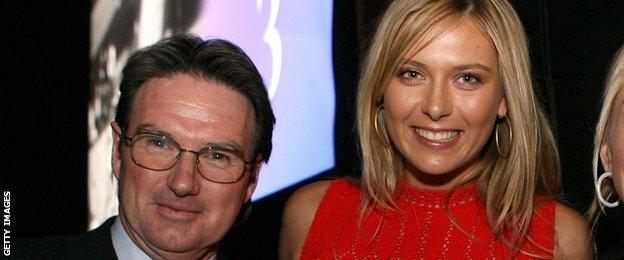

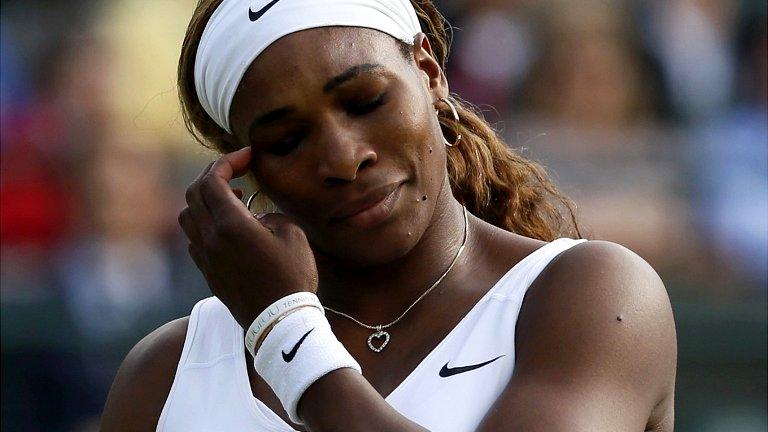

Maria Sharapova's experiment with Jimmy Connors, external died before it had truly begun. Serena Williams's longevity and renaissance has much to do with Patrick Mouratoglou, a far more traditional coach and one who, despite his personal relationship with Williams, can still walk the concourses of Wimbledon entirely unrecognised by most spectators.

Maria Sharapova sacked Jimmy Connors after one match describing the partnership as "not the right fit"

"They're not after the champion status," believes Woodforde. "They want someone to feed balls to them on the practice court, to be that emotional shoulder.

"Some of the players will employ someone just to be there, just to keep them going. But the women's game tends to follow the men's. They'll catch up soon enough."

Then there is the other great contradiction: Rafael Nadal, 14 Grand Slam titles to the good, and coached now, as he has always been, by his uncle Toni.

No big name, no big changes. And, by results, as super a coach as any of the others.

- Published28 June 2014

- Published28 June 2014

- Published28 June 2014

- Published22 June 2014

- Published17 June 2019