Serving for Success - Anyone for Tennis?

- Published

Serving for Success: Anyone for Tennis?

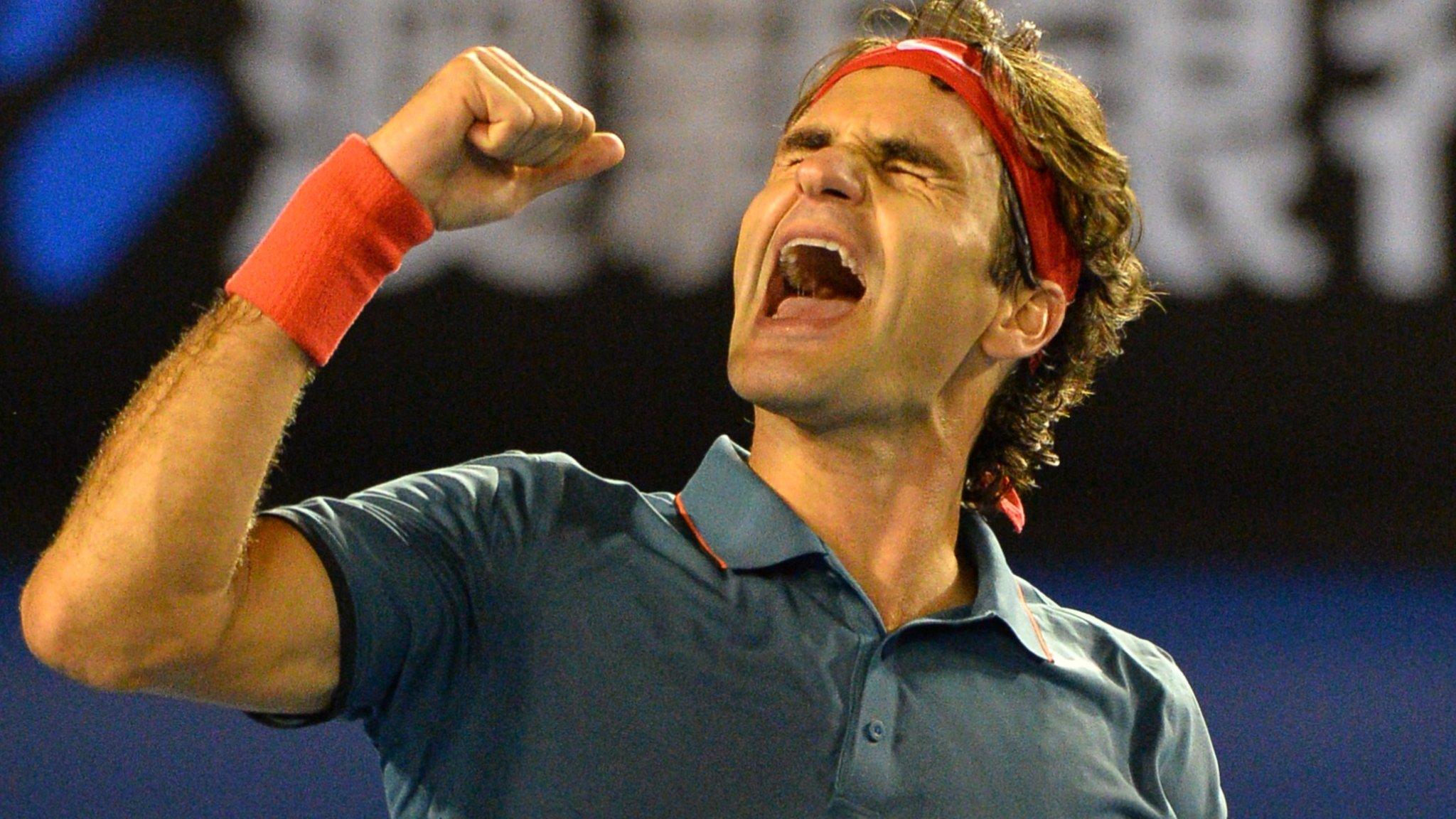

The phrase "Anyone for tennis?" may have entered popular parlance 100 years ago but today the sport is played by super-fit athletes.

The modern professional is a hard-hitting powerhouse - strong, quick and agile.

Reaching the top of the tennis tree in the 21st century relies on intense physical training with the appliance of science and technology.

"When you play tennis these days you need everything," French player Jo-Wilfried Tsonga, the 2008 Australian Open runner-up, told the BBC.

"You need to be quick, you need endurance and you need to be powerful."

This physicality is also prevalent in the women's game, where the top players are capable of firing serves close to 130mph (210kph) - just 30mph slower than the top men.

"It's all about power," says 2012 Wimbledon finalist Agnieszka Radwanska.

"Instead of just being about technique, it's more physical and much faster. There's a lot of difference between tennis now and 20 years ago."

Modern demands modern techniques

The evolution of tennis from a deft serve and volley game to power play from the baseline has led to an anatomical player evolution too.

"You need to be a complete athlete," explains Matt Little, strength and conditioning coach for 2013 Wimbledon champion Andy Murray.

"The players can move at speeds of 20-30 metres a second on court but they might also be out there for as much as five hours, which is marathon runner levels of endurance.

"Rallies can last up to 60 metres in terms of sprinting length, with any number of changes of direction.

"There are huge forces, three or four times the player's body weight, going through a single leg."

To cope with the stresses and strains on the body, players can spend as many as 35 hours a week getting match fit.

Old-fashioned hitting practice on court still forms the bulk of the training but the modern demands of the game means this has to be supplemented by a rigorous fitness regime.

"I usually train for two hours in the gym each day," says Japan's 2014 US Open finalist Kei Nishikori. "I focus on a lot of core work and running for endurance."

United States number one John Isner adds: "It's a grind. I practice for two hours on court and then spend time in the gym doing core work and leg strengthening."

Murray adds flair to the training treadmill by attending hot yoga classes while Radwanska says she likes to dance.

But advances in sports science and tennis technology are now also helping players hone what nature has given them and reach their peak physical potential.

Inside the modern London headquarters of the Lawn Tennis Association, the sports science and medicine facilities are playing an increasing role in physically preparing British players like Murray.

Technology revolution

Its high-tech facilities include an altitude chamber, hydrotherapy pools and cardiac screening.

"We do hydration and blood lactate testing on the players so we can learn as much as we can about their bodies," explains Little.

"The altitude chamber helps mimic conditions for players travelling overseas and there are fitness gains to training with limited access to oxygen.

"We also use GPS [global positioning system] equipment to monitor a player's speed and direction of movement.

"The confidence a player has going into a match knowing no stone has been left unturned in their physical training is absolutely huge."

The LTA also employs the Hawk-Eye tracking technology - used during grand slam tournaments to show whether a ball is in or out - as a coaching aid for its elite players as it monitors the trajectory of the ball and the player's on-court movement.

The Kim Clijsters Academy in Belgium is the only other facility to use Hawk-Eye as a training aid.

Tennis technology is, however, now moving away from the practice court and into the high-pressure cauldron of the match court.

The sport's governing body, the International Tennis Federation, has radically updated its rules for 2014, giving the green light for what it calls "Player Analysis Technology" to be used during matches.

This technology includes heart-rate monitors and player tracking systems, which transmit information in real time.

"The market is now open," says Max de Vylder, the LTA's research and development manager.

"Until now we could only monitor a player using TV footage or Hawk-Eye but now we can put data chips in shoes and in racquets. Players can wear heart rate monitors and accelerometers.

"What technology does is help a coach and a player understand better and faster what their strengths and weaknesses are.

"In the short term, technology can help players be ready for the next match, but in the long term it can lower bad technique and the risk of injury."

Ability mix

Advances in technology have already shaped the physical nature of the modern tennis player.

The evolution from small, wooden racquets to super-size composite racquets at the end of the 1970s changed the game for good, increasing spin, power and shot creativity.

"The old, heavier wooden racquets were very unforgiving and by the fifth set you could be exhausted," explains Ralf Schwenger, director of research and development for racquet manufacturer Head. "Modern technology has helped a lot.

"The carbon or graphene frame can now weigh around 250g while a wooden racquet was 400g. The trend is also towards a mid-plus size racquet, which is 96-105 square inches (600-680 cm square).

"The revolution of the racquet is important. Now it's easier to have a margin of error, to play defensively and have less fatigue in your game."

Despite the march of technology into equipment, training and onto the courts, the human body remains the most important tool in tennis.

But when asked to describe a perfect tennis body, Little had to choose characteristics from a selection of today's stars.

"You need the incredible strength of Rafael Nadal and Andy Murray," he suggests.

"The balance of Roger Federer, the endurance of David Ferrer, the power of Serena Williams, the flexibility of Novak Djokovic and the fun of Gael Monfils."

Even at the top of the tennis tree, it seems no body is perfect.

Reporting by Sarah Holt

- Published30 September 2014

- Published7 October 2014

- Published13 October 2014

- Published8 September 2014

- Published9 September 2014